'A collective failure': 140,000 children died from measles in 2018

More than 140,000 children died from measles in 2018 - but experts have warned that the number is likely to be far higher this year.

An analysis of annual measles figures released by the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that last year there were a staggering 9.7 million cases of measles and 142,300 deaths – the vast majority of which were in children under the age of five.

The 2018 figures are an increase on the 2017 total when there were 124,000 deaths and 7.5 million cases.

There has been a global resurgence of the disease in the last few years due to poor measles vaccination rates. The reasons for this rates are complex but a lack of access to the vaccine, weak health systems and anti-vaccine concerns stoked by social media are to blame.

The Western Pacific island of Samoa has become the latest country to be gripped by an outbreak of this highly infectious disease, with international medical teams flying in to help treat the desperately sick and implement a nationwide vaccination campaign.

The tiny island nation of less than 200,000 saw vaccination rates plummet after the deaths of two children who were administered the measles jab incorrectly.

Over the last few weeks the virus has infected more than 4,000 people and, as of December 4, had killed 62, most of whom are children under the age of four.

Dr Kate O’Brien, director of WHO’s department of immunisation, vaccines and biologicals warned that the global total of cases of this highly infectious disease is likely to be much higher this year.

WHO and CDC use statistical modelling to form their estimates as the data officially reported to WHO by countries is only a tiny proportion of the actual number of cases.

In 2018, 353,000 cases of the childhood killer were reported to WHO. But by mid November of this year WHO had received reports of nearly 700,000 cases of the disease – a three-fold increase on the number of case reports received at the same point in 2018.

Dr O’Brien said the measles outbreaks were the sign of a “collective failure” as there was a safe, effective and affordable vaccine available.

“The underlying reason [for the outbreaks] is that people are not vaccinated. There is an immune gap and that’s because of a failure to vaccinate,” she said.

She added: “Unfortunately, we have been backsliding. There’s been an increase in the number of cases and deaths and we know that we’re actually seeing an increase in the reported cases to date in 2019 which will substantially exceed the number in 2018.”

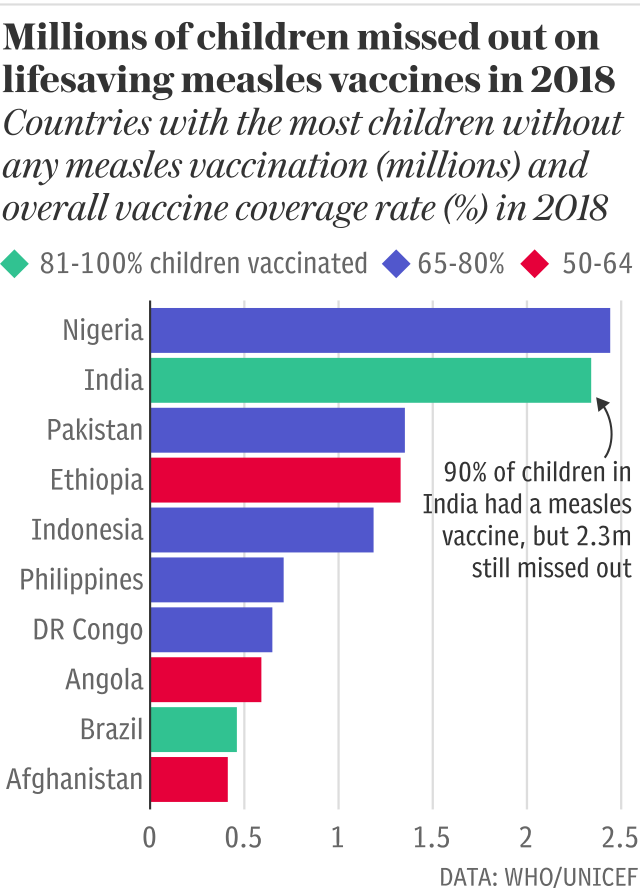

In 2018, the most affected countries were Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia, Madagascar, Somalia and Ukraine. These five countries accounted for almost half of all measles cases worldwide.

Professor Heidi Larson, an expert in vaccines at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said “stressed systems” alongside conflict and distrust have contributed to the outbreaks.

“Two of the countries with the highest number of cases faced other devastating outbreaks. Liberia’s Ebola outbreak in 2014-2016 and Madagascar’s plague outbreak in 2017 took a toll on their health systems.

“DRC, Somalia and Ukraine, the other countries hardest hit by measles, each face conflicts, with DRC additionally battling a serious Ebola outbreak and rampant distrust. Ukraine has rumours and mistrust swirling alongside conflict and historic vaccine supply gaps, she said.

This year, the United States reported its highest number of cases in 25 years, while four countries in Europe – the UK, Albania, Czech Republic and Greece – lost their measles elimination status in 2018 following long outbreaks of the disease.

However, Dr O’Brien stressed that since 2000 the number of measles cases and deaths has actually fallen dramatically. In 2000 more than half a million people died from the highly infectious disease.

She said that the gains made in reducing cases and deaths were due to expansion in access to the vaccine – but vaccination rates have stalled and there has been little progress in the last decade.

“We have to really move from putting out fires and responding to outbreaks all the time. We have to focus on strengthening the essential immunisation programmes so we’re not facing these situations country by country, month in month out, year in year out,” she said.

Symptoms of measles include high fever, rash and respiratory symptoms. It can also lead to pneumonia and encephalitis – inflammation of the brain. Blindness and permanent hearing loss can also occur.

Recent research has also shown that measles can damage the immunity of those infected for up to five years, said Dr O’Brien.

“People who survive the measles event are not out of the woods and are at high risk of other infections that can go on to cause serious illness and death. That’s called immune amnesia,” she said.

Charlie Weller, head of vaccines at Wellcome, said it was a tragedy so many children were dying from a preventable disease.

She said: "These latest figures from the WHO underline the urgent need for an increased focus in low-income regions to ensure vaccines reach those who need them the most.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Yahoo News

Yahoo News