'Comedy is my way of making sense of life': the comics standing up for mental health

“Every time you get depressed, comedy will be there to drag your ass out of it,” said Robin Williams in 1996. It is a gut-punch of a quote, considering that depression was one of the factors that led to his death 18 years later (although his wife has said the main reason for his suicide was probably the debilitating brain disease diffuse Lewy body dementia). It also speaks to a nagging sense that there is some truth to the “tears of a clown” cliche: that many of those who seek to make us laugh are masking private sadness.

The list of comedy greats who have had some form of mental illness is long: Richard Pryor, Spike Milligan, Caroline Aherne, Stephen Fry, Joan Rivers and Kenneth Williams to name a few. The doubters say that it is no more common among comics than anyone else – they are just more cognisant of the bad stuff in the world and have the outlet to talk about it.

So what of today’s comedians? Is comedy dragging their ass out of anything? “It’s where I found all my joy when I was having a tough year, with heartbreak and losing a close family member,” says Suzi Ruffell, who has appeared on TV shows including Mock the Week and The Last Leg. “Performing was the one thing that was just mine. On stage, I was talking about how shit things were and people were laughing, and I often think that is them saying: ‘Me too, I’ve felt that.’ If it wasn’t for that, my healing process would have taken a lot longer.”

For John Robins, a BBC Radio 5 live DJ and Edinburgh Comedy award winner, the stage is a safe place and “an island of control” – but the process of writing comedy helps him more than the performance, he says: “Standup is my way of making sense of my life and how I feel about myself. Often, I don’t really get a handle on what’s happening until it’s found a life in a routine.

“There’s a lot of nonsense written about ‘comedy as therapy’ – the therapy is the writing bit that happened eight months ago, the practice that happened six months ago, the honing that happened four months ago. There have been moments when I’ve been writing difficult bits, I’ve been sitting in my kitchen in floods of tears because I didn’t realise the way I felt until I wrote it down. By the time most people see it, I’m totally over that bit.”

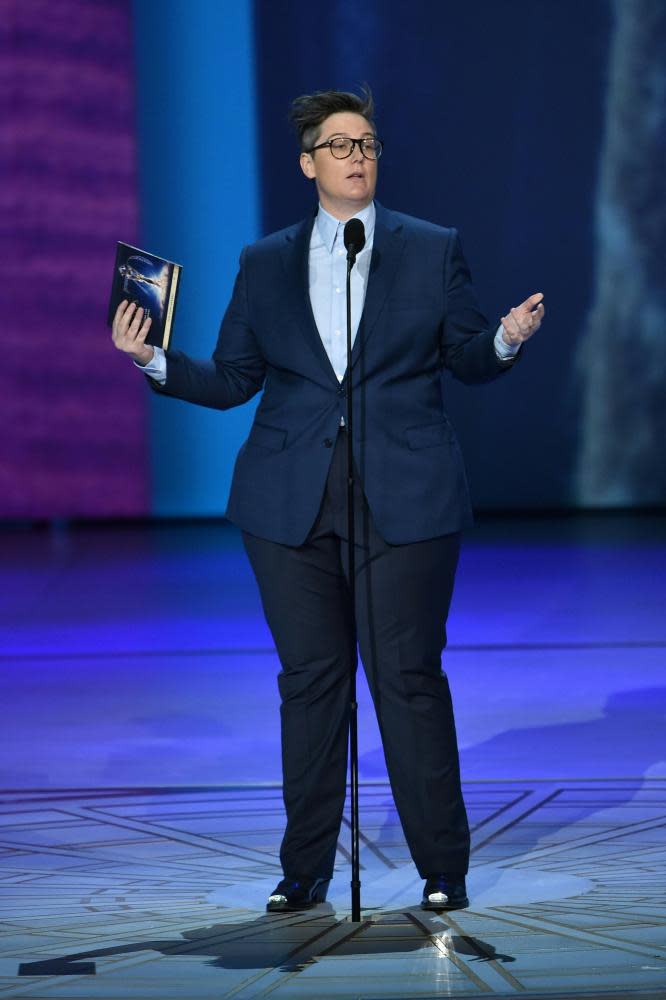

It is a timely moment to revisit the subject of comedy and mental health, as some of its moving parts have shifted in the past decade. First, standups have been increasingly open about their mental health and traumatic episodes in their life. Some tackle this in an unobtrusive way, letting the stories of life’s ups and downs speak for themselves, but many (notably Kim Noble and Hannah Gadsby) have laid it bare in shocking detail. Last year, the documentary Laughing Matters got comics (such as Sarah Silverman and the US Office’s Rainn Wilson) off the stage to tell their stories without the jokes in between.

The second big change has been the rise of social media, which has increased exposure for all, but especially those in the public eye. Third is the conversation around mental health, which has become far more sensitive, sophisticated and widespread. When a major broadcaster has a “silent ad break” to encourage people to check in with each other – as ITV did last autumn – you know mental health has gone mainstream.

Broadcasters are doing their bit again this week, with Comedy Against Living Miserably, a three-part series on Dave in association with the mental health charity Calm. In each show, comics – including Ruffell, Robins, Nish Kumar, Kiri Pritchard-McLean and Darren Harriott – will speak about everything from grief to anxiety to gaslighting and perform material on these subjects. As Robins says: “Mental health is life. As a standup, you’re talking about your life, your experiences, good and bad. Everyone has mental health.”

But for all the introspection that comes with standup, this generation of comics are a responsible lot. Ruffell and Robins are aware of how much their comedy can benefit their audiences, too – especially at a time like this, which feels bleak and lonely for so many. Robins says people have told him (“the partners, usually”) that his radio show with fellow comedian Elis James has got them through a tough time. Off the back of that, Robins and James started a podcast, How Do You Cope?, that is aimed squarely at the subject of mental health.

Ruffell’s experience of how her comedy can help others will be an eye-opener to many: “I’ve had people travel 100 miles [to one of my shows] because they wanted to bring their gay teenage daughter to see me, because she doesn’t have a gay network at all. On more than one occasion, I’ve had a teenager say to me: ‘When you’re on TV, it reminds my mum that I’m normal.’ So it’s really important that they get to see someone like them under a spotlight talking about their experiences.”

Robins recognises, however, that comedy has limits in its influence. As a comic on stage, the best he can hope to achieve is “thousands of tiny impacts”. The same applies to many mental health campaigns, he says – the hashtag slogans #bekind and #reachout are “absolutely vital right now”, but a drop in the ocean in the context of “services that are so stretched and so cut that they barely exist”. He says: “The best way to actually improve the nation’s mental health is to pay your taxes, encourage companies to pay their taxes and vote for a government that will spend that money in the most useful way, regardless of what political colour you are.”

The flip side of all this is that being a standup can also exacerbate mental health problems. It is a solitary job, with unpredictable results from one night to the next and little security in the long term, which is hardly a recipe for a settled existence. Robins says that writing a show requires “holding yourself in places of anxiety, frustration or anger, and that isn’t a healthy place to be”. The Laugh Factory comedy club in Los Angeles has gone as far as getting an in-house psychologist, who was hired because “recognised that comedians needed more support than he could provide”.

And then there is social media. Being active online is almost obligatory for comics today – and a necessity now that the possibility of performing live is gone for lord knows how long. The Faustian pact they make is that they give more of themselves away; they are “on” when they are padding around at home, not only when they are on stage. “People want a fuller idea of what a comic is these days,” Ruffell says. “I don’t mind sharing a bit more, but not everyone does, and if I see another comic sharing too much or tweeting certain things I’ll send them a text just saying: ‘Are you OK?’ We do have to look out for each other. For the sake of my mental health I have to tweet and not scroll.”

More alarmingly, she says: “The thing that’s affected me the most [from social media] is the element of threat. I had this troll that just kept on saying: ‘I’m gonna rape you straight.’ That’s a really weird thing to read when you’re at a train station, travelling home by yourself. Sometimes it happens on the way to a gig and you have to go on stage and be all: ‘Hey! How’s everyone doing?!’ It’s an extra thing people don’t consider that wears away at you.” The murder of the Melbourne-based comedian Eurydice Dixon in 2018, after a gig, shows that comics must tread the difficult line between taking such threats seriously and living their lives.

But these are boom times for standup. There are more touring comics than ever before and more TV opportunities. The nature of the form means that, the second a comedian get on stage, with the spotlight and the mic, they have authority – and we in the audience or at home put them on a pedestal. The fact that many comics want to use this soft power for good is a start. As Ruffell says: “I just hope there are people out there who watch the show and feel less alone.”

Comedy Against Living Miserably starts on Dave on 24 March at 9pm

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailing jo@samaritans.org or or jo@samaritans.ie. You can contact the mental health charity Mind by calling 0300 123 3393 or visiting mind.org.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News