Why some WAGs will always stand by their men

When Tammy Wynette recorded Stand By Your Man in 1968, neither the term WAG nor the concept of ultra-loyal footballers’ wives and girlfriends were known in Britain.

Yet today, it is a very rare thing indeed to see the lover of a Premiership star do anything other than show the sort of devotion the country singer implored in her hit song.

We saw this commitment in evidence yesterday when Stacey Flounders, the girlfriend of England winger Adam Johnson vowed to stand by him after he was arrested on suspicion of having sex with a 15-year-old girl.

We also saw it when Natasha Massey, the girlfriend of Sheffield United striker Ched Evans, stood by him when he was convicted of rape. Of course we do need to make it clear that Johnson and Evans are two distinct cases at this moment in time. Johnson was only arrested yesterday, nothing has been proven and accordingly we should not rush to make any value judgements on his friends and family for standing by him. But when it comes to Evans he is incontrovertibly a rapist - he has been found guilty in a court of law.

Another example of conspicuous WAG loyalty was Toni Poole, the wife of John Terry, who agreed to give the Chelsea star “one last chance” when he cheated on her with a teammate’s lover.

Now, it’s just a hunch, but I suspect the reason footballers can now expect great shows of loyalty is because they earn so much more than everyone else.

Football is, of course, an extreme example of wealth and the envy and idolisation that follows.

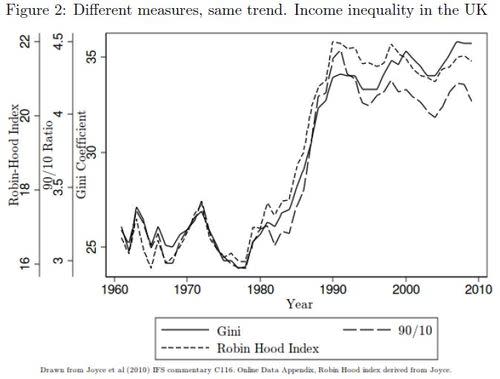

But the big bucks earned by players of the beautiful game – and the deference of hangers on - is emblematic of a general society poisoned by growing inequality.

Back in 1968 – seven years after the League axed its £20 wage cap – top-flight players typically earned £85 a week.

Yet, despite a four-fold rise since 1961, their incomes were only three times the average wage.

So, if a WAG back then had wanted to date someone with a similar salary, she would have only needed to reveal her charms to a bank manager.

Furthermore, in 1968, the richest fifth of British families received only three times as much income as the poorest fifth.

Today, the typical Premiership star earns £2.3million a year (£43,717 a week), which is almost 87 times the average annual salary of £26,500.

And the richest fifth of Britons earn 7.2 times as much as the poorest.

To put this last statistic into perspective, the richest 20% in Japan earn only 3.4 times as much, while in Finland it is 3.8, Germany 4.3 and Canada 5.5.

In fact, among industrialised countries, only Singapore (9.7) and the U.S. (8.4) have a greater level of income inequality.

So with such vast differences in wealth in our general society, it is little wonder that so many people yearn to be like footballers and other super-rich celebrities.

They are only the most publicised examples of the “get-rich-or-die-trying” culture that encourages bubbling envy and deep social anxiety.

Now, I’m not saying we should have nothing to aspire to, but Britain’s staggering wealth gap makes for a much less harmonious society – fostering greater levels of crime, ill health and other social problems.

The assumption that income inequality does not matter so long as it does not increase poverty and we have equality of opportunity is wrong.

In their best-selling book The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, authors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett found that “almost all problems that are more common at the bottom of the social ladder are more common in more unequal societies.”

They found evidence that showed that rising general affluence will do little to tackle social problems once they have reached a general wealth “plateau”.

Beyond these issues – and getting back to where I started – rampant inequality also promotes frankly shameful levels of deference towards those who have money.

Too often poor people assume the rich are better than themselves – and consider their lack of money a moral failure.

Yet real moral failure is among those so greedy that they tell us that we can spend what little tax they choose pay on bankers and wars but not on helping people.

It may be because I was raised a Catholic (I am now lapsed, admittedly), but I do really wonder what ever happened to the idea of avarice being a sin.

But I will end, not with a quote from Jesus about camels and rich men, but from the philosopher Adam Smith, whose distilled concept of free-market capitalism we are now so in thrall to:

“The disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition is the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News