Compositrices: New Light on French Romantic Women Composers review – treasure trove of the overlooked

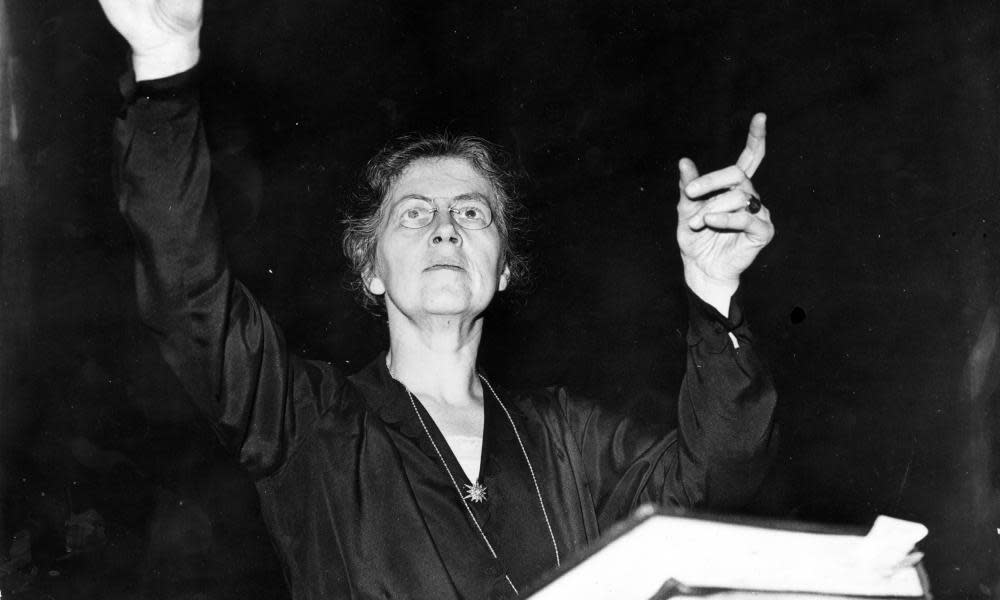

Twenty-one composers, with dates of birth ranging from 1764 to 1893, are represented in this always fascinating and sometimes revelatory collection of more than 160 pieces, from which only a handful of the names will be familiar to even assiduous concert goers and record collectors on this side of the Channel. There are works here by Nadia Boulanger, perhaps the most influential composition teacher of the 20th century, and her hugely talented sister Lili, who died at the age of 24, as well as by Pauline Viardot, best remembered as one of the greatest of 19th-century singers, and Cécile Chaminade, whose songs crop up occasionally in recitals. The music of Louise Farrenc, Augusta Holmès and Hélène de Montgeroult (the earliest composer in the set) has become much better known in recent years too, while Charlotte Sohy was featured in a CD collection just last year. But the remaining 13 composers are much less well known, and until recently many of them were hardly ever performed and recorded.

Much of the repertoire included here is generally small-scale – chamber works, piano music and a lot of songs – and the quality of some of these pieces, the songs especially, can be uneven. Yet each of the eight discs includes at least one large-scale orchestral score and they are shared between the French national orchestras from Paris, Toulouse and Metz, and the period-instruments of Les Siècles. There is the third and last of Farrenc’s symphonies, and Sohy’s Symphony in C sharp minor, which was never performed in her lifetime and only heard for the first time in 2019. We have Chaminade’s Concertino for Flute and a rather pallid suite from her ballet Callirhoë, Holmés’s symphonic poem Andromède, with its hints of Wagner’s Valkyries, and Nadia Boulanger’s cantata La Sirène, with which she won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1908.

It’s certainly among the orchestral pieces that the real rewards are to be found. There’s also the striking, Lisztian symphonic poem Ossiane, with its solo soprano in the second movement, by Marie Jaëll, a pupil of César Franck and Saint-Saëns, who was the first pianist to perform all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas in Paris, and, for me, the biggest discovery of all, the three pieces in the Femmes de Légende series, Le Rêve de Cléopâtre, Ophélie and Salomé, by Mel Bonis, which are wonderfully crafted miniatures clearly indebted to Debussy, but at the same time distinctively individual. Bonis is represented in the set by some of her piano music and songs too, all of which makes one want to hear much more of her music.

This kind of meticulously assembled survey, expertly performed and beautifully presented with scrupulous documentation (though without texts and translations for the many songs) does far more for the cause of these unjustly overlooked composers than any number of books making grand claims about their importance; those championing their British equivalents would do well to follow its example.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News