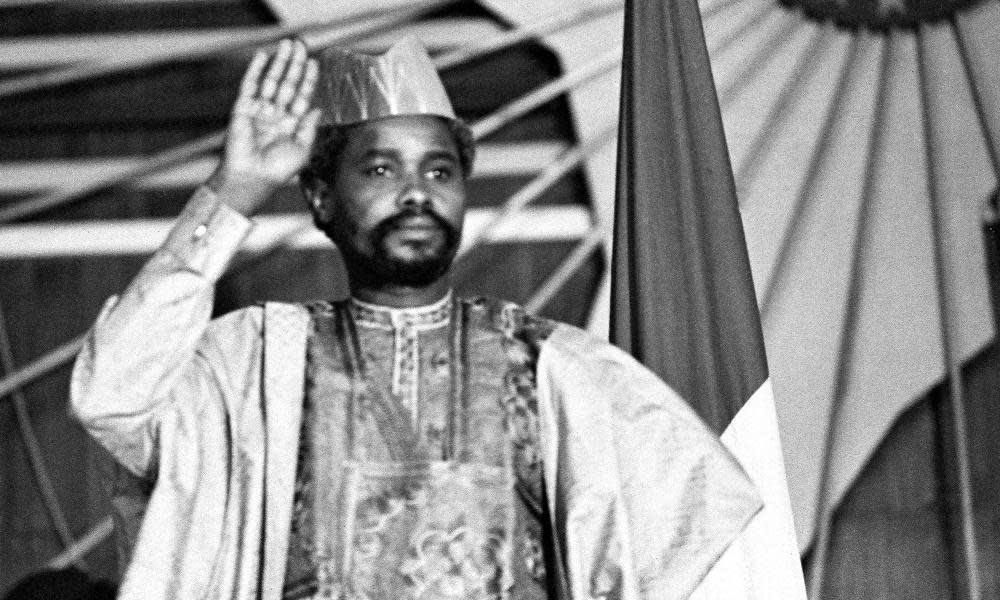

Ex-Chad dictator's conviction for crimes against humanity upheld by Dakar court

An African court has rejected Hissène Habré’s appeal against his conviction for crimes against humanity, which followed a decades-long fight for justice for his victims.

The former president of Chad was acquitted of a rape charge, but all the other charges against him – including torture and murder – were upheld.

Last year, Habré was sentenced to life in prison in Dakar, Senegal, for ordering the wrongful arrest, torture and killing of Chadian citizens throughout his tenure as president in the 1980s.

He was made to listen in court as 90 witnesses testified that he had thrown thousands of people into secret jails, where they had been tortured, executed or forced to endure horrific prison conditions.

“I have been fighting for this day since I walked out of prison more than 26 years ago. Today, I finally feel free,” said Souleymane Guengueng, who almost died in one of Habré’s jails and swore he would fight for justice if he ever got out. He did, and spent years collecting files full of victims’ testimonies.

Some of the trial’s most powerful testimony came from Khadidja Zidane, who accused Habré of raping her four times and whom his website described as a “crazy whore”.

In an interview with the Guardian last year, Zidane said she would never be satisfied while Habré lived in a comfortable prison cell, but added: “At least I was able to face him. If I die today, I’ll die in peace. I had the opportunity to tell the whole world what he did to me. Thank Allah for that. He’ll pay in the afterlife for what he did.”

Although Ougadeye Wafi, the Malian judge who read out the verdict, said the court believed Zidane’s account and found her a credible witness, he said he could not uphold the rape conviction as it was not on the original indictment. However, it makes no difference to the sentence.

Habré will continue to serve his life sentence in jail in Senegal, the country in which he took refuge after being ousted in a coup in 1990. It took 10 years for him to be arrested by Senegalese authorities and another 13 for the country, along with the African Union, to create the Extraordinary African Chambers, a court specially made to try Habré.

He was absent for the appeal, which was conducted for him by lawyers who had no contact with their client. Habré was ordered to pay more than £100m to his victims in reparations, and the court said a trust fund set up by the African Union should search for his assets to this end.

When the verdict was read out last May, scenes of high tension were followed by jubilation among his victims, along with the lawyers and human rights activists who had fought for justice for 26 years.

This time, the joy was more muted: quiet singing echoed around the chamber at Dakar’s Palais de Justice, but there were no shouts of triumph, no tears, no defiant Habré shaking his fist.

“Today will go down in history as the day that a band of unrelenting survivors finally prevailed over their dictator,” said the human rights defender Reed Brody, whose painstaking work, alongside the lawyer Jacqueline Moudeina and victims led by Guengueng, was central to the case.

Some have expressed worry that Habré could be given a pardon by the Senegalese president, Macky Sall, or his successor. However, Moudeina thought this unlikely.

“I don’t believe that Senegal will undo all its wonderful work on this case by freeing Habré,” she said. “A pardon would not only violate Senegal’s treaty with the African Union and its obligations under the UN torture convention, it would be a slap in the face to the victims after all they have been through.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News