Coronavirus: Advisers warned of need for action to stem infections ‘virtually every day’

Boris Johnson’s top medical and scientific advisers warned the government “virtually every day” since mid-September of the need for action to bring coronavirus infections down, MPs have heard.

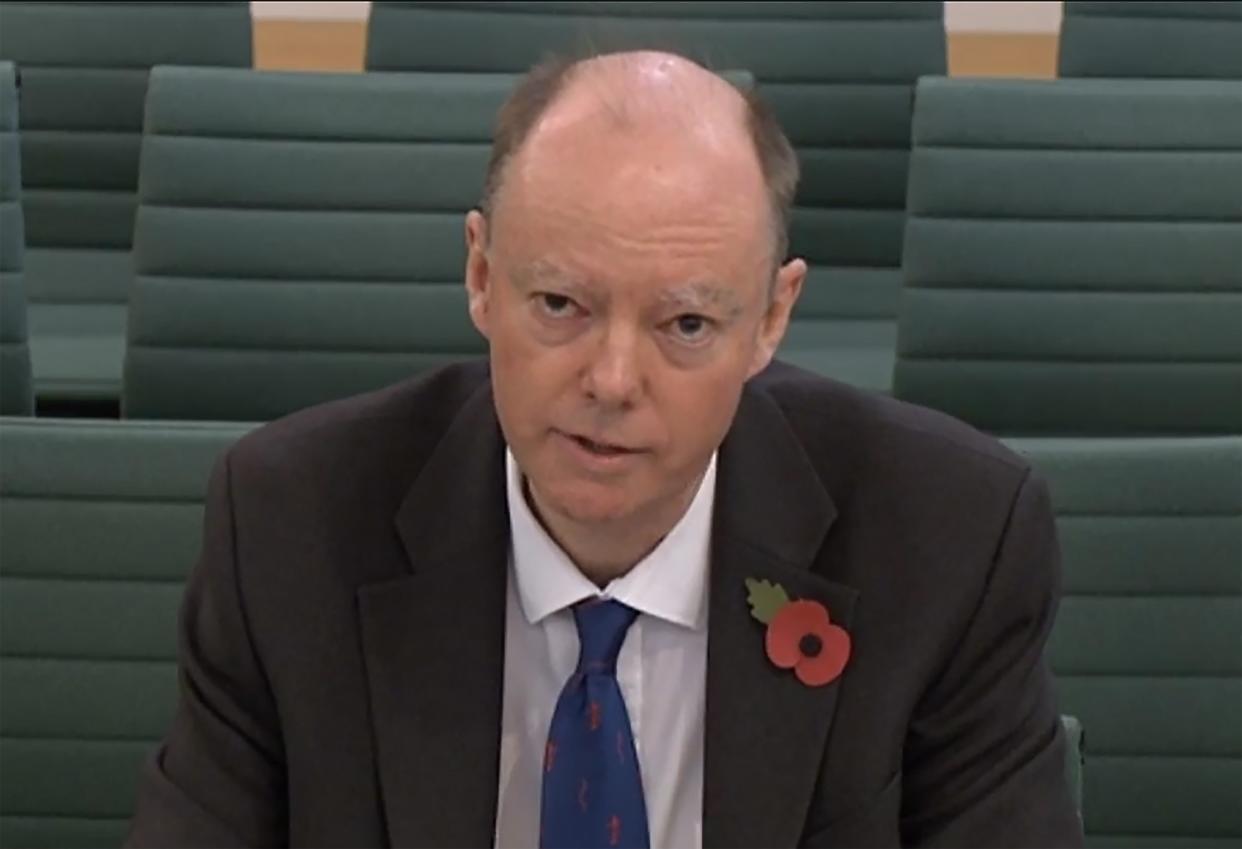

Chief medical officer Chris Whitty told the Commons Science and Technology Committee that it was clear hospitalisations were on an “exponential curve” upwards, with inpatient numbers topping 10,000 in England today and set to increase.

Hospitals have already begun to cancel elective procedures and may have to begin postponing urgent operations if their intensive care wards keep filling with Covid patients.

Asked whether there was a “serious prospect” of the intensive care capacity of the NHS being overrun within six weeks, chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance told the committee: “If nothing is done, yes.”

Vallance told the committee that evidence from around the world showed it was important to “go quite early and go quite significant” in taking actions to stem the spread of the disease, even at a time when the scale of the problem has not become evident.

Scottish National Party MP Carol Monaghan asked the pair how often they had advised ministers of the need for action between 21 September, when the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) first recommended a two-week “circuit-breaker” and 31 October, when Mr Johnson finally announced a month-long England-wide lockdown.

“I think that we’ve been consistent all the way through that there is an increase coming and therefore if you want to do something about it, the increase doesn’t go away on its own,” said Prof Vallance.

“I think probably Chris and I have been in meetings virtually every day.”

Both men stressed that they accepted that ministers had to weigh up not only their medical and scientific advice about how to contain Covid-19, but also the social and economic implications of restrictions on normal life. It was for democratically-elected politicians to make these decisions, they said.

Prof Whitty said he expected the lockdown restrictions coming into effect on Thursday, which will close pubs, restaurants and non-essential shops and require people to work from home if possible, to reduce the reproduction rate of the virus - known as R - below the crucial level of one at which it ceases to spread exponentially.

“If people adhere to it in the way that I expect they will, it’ll reduce R below one, in my view, in the great majority or all of the country,” he said. “That will pull us back in time and that will make a huge difference.”

But he added: “What I wouldn’t want to imply is that suddenly that means that Covid is over as a problem. This is a long haul.

“I think people broadly accept that we need to see this through winter. This doesn’t mean we need to stay in these measures through winter, but we will need to be doing things that keep the rates down.”

Prof Whitty told the committee that Covid inpatient figures in English hospitals had grown from 536 on 7 September to pass 2,500 at the start of October and 10,000 today.

“You don't need too much modelling to actually tell you you are on an exponential upward curve,” he said.

“What we know, with all epidemics, is that epidemics are either doubling or halving. This is currently doubling.”

Some hospitals in the north of England now have more Covid patients than at the height of the first wave in the spring and could “get into serious trouble on inpatients very quickly” if R remains above one, he said.

Meanwhile, infection rates are rising in areas which have so far lagged behind the rest of the country in entering the second wave, such as the southwest of England, which could “hit difficulties relatively quickly”, he said.

It was an “entirely realistic scenario” that the first-wave peaks of more than 1,000 deaths on multiple days might be repeated, said Prof Whitty.

Non-urgent elective care was already being cancelled in some areas and failure to bring R down would lead to urgent non-emergency operations, and later all non-Covid care, also being affected.

Projections released on Saturday suggested that, without the introduction of tighter restrictions, the number of hospitalisations across the country could be expected to top the first-wave peak towards the end of November, and deaths by mid-December, the committee heard.

“Quite a small R can take you from just about coping to not coping,” said Prof Whitty.

“So the chances that things are likely suddenly somehow to improve without action between now and the next few months are quite low.”

Prof Whitty said he was confident that Mr Johnson’s three-tier regional restriction system had kept infection rates in tier 2 and 3 areas “substantially lower than they would have been” and had slowed the doubling in cases, but told MPs that it had not succeeded anywhere in getting R below one.

It was not possible to wait and see what further impact the tiered system has before moving to a tougher lockdown, because “a very large backlog” of cases could build up in the time needed to assess whether it has been a success, he said.

Read more

As another lockdown looms, we are not in a much better position

The new lockdown rules around weddings, funerals and places of worship

Can hotels remain open during lockdown and who can stay in them?

Yahoo News

Yahoo News