Could a 2100BC sex epic show us how to handle Trump?

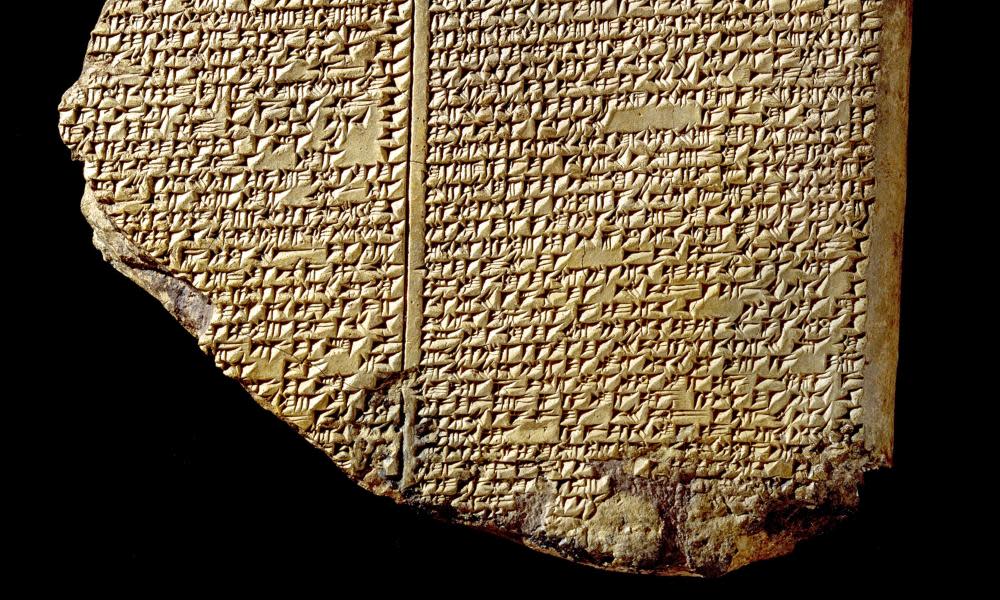

A new bit of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest literary text, has turned up, which is no great news in itself: fragments of clay tablet telling the story of the tyrannical Sumerian king are periodically unearthed, and there is a thrilling expectation that they will continue to be so indefinitely. The narrative has therefore been subject to change, expansion and gap-plugging from its beginnings, in 2100BC, to the Akkadian versions made by copyists (often prisoners of war) in the scriptorium of Nineveh for the pleasure of King Ashurbanipal.

But the latest twist has piqued the interest. Why? Because it is about sex. It tells us that Enkidu – a very hairy man who grazed with gazelles and freed the beasts from hunters’ traps – was civilised after a mammoth Mesopotamian shagging session that lasted not, as previously thought, a mere week, but an entire fortnight. Ouch.

The idea of a man undergoing fundamental change after succumbing to carnal delight has been a complex and recurring one throughout literary history, and it is no different here. Enkidu seems to have been perfectly happy before the arrival of Shamhat the harlot – an emissary of the gods, who wish to create an equal to the out-of-control Gilgamesh to rein him in. The king’s bad behaviour is itself sex-based: he likes to pop in to the city of Uruk’s marital chambers on wedding nights and, to put it crudely, have first dibs on the brides.

Is Enkidu, in that context, a force for good? Alas, not quite. After his sex spree has opened him up to new possibilities, he does indeed attempt to influence Gilgamesh, coming to blows with him over the issue of droit de seigneur. But once he loses, he appears to fall in quite happily with the Gilgamesh programme: Enkidu is adopted by his new friend’s mum, the goddess Ninsun, and soon the pair are off vanquishing an ogre and killing Taurus. “Like a wife you’ll love him,” Ninsun tells Enkidu; and, sure enough, when Enkidu dies of sickness, rather than in glory on the battlefield, he curses Shamhat for weakening him. Gilgamesh responds in typically dramatic fashion, promising that “like a hired mourner-woman I shall wail”.

What is the function of sex here? Removing Enkidu from his lovely life in the forest (bad), or introducing him to a life of adventure and palace privilege with Gilgamesh (good, up to a point)? In terms of the original point of the exercise, to protect the brides of Uruk, it seems to have been a failure; certainly, no more is said of them.

Millennia later, we still haven’t managed to get our heads around it. Literature is studded with those for whom sex has been disastrous, from young Werther to Anna Karenina to Tess Durbeyfield (and, ultimately, Alec d’Urberville) to 1984’s Winston and Julia. In general, it is far worse for women than it is for men – that Shamhat doesn’t appear to suffer is presumably because she is a temple prostitute under divine command.

But what of the latent idea that men can be used to civilise one another? In the age of #MeToo, it seems a flawed ambition: the bad men appear to egg one another on to greater feats of devilry and provide limitless amounts of cover, all the time calling the good men pussies. Literature might give us more hope: Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, for example, Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson; and, more recently, the drug-addled teenagers Theo and Boris in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, who are hardly models of upstanding behaviour but who (sort of) come through for one another in the end.

But The Epic of Gilgamesh is, among other things, about the problem of constraining a powerful and narcissistic leader, even if you have to send him (literally) to hell and back in the process. What steadying person might exercise that influence on, say, Donald Trump? It wasn’t Reince Priebus and it wasn’t Anthony Scaramucci. It really wasn’t Kanye West. We hoped it might be Gen John Kelly, but that’s not looking too hot either. Perhaps only if the encouragingly named John Legend would agree to take one for the team could we begin to hope.

As the Gilgamesh translator Andrew George notes, in his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke was entranced by the work, hailing it as das Epos der Todesfurcht – the epic about the fear of death. The battle for “civilisation” over “savagery” suggests that fear still looms large in the conduct of our most overweening leaders. We’d better keep taking the tablets.

• Alex Clark is a literary journalist and editor

Yahoo News

Yahoo News