A Countervailing Theory at the Barbican review: Toyin Ojih Odutola's tantalising drawings tell us stories about ourselves

Let me tell you a story. Or rather, let the American artist Toyin Ojih Odutola tell you a story. But not the whole story. Oh no. That’s for you to tell yourself. Ojih Odutola’s commission for the Barbican’s Curve space (her first UK exhibition) is a deep dive into the way we create stories and how drawing — our oldest art form — can be wielded to do that.

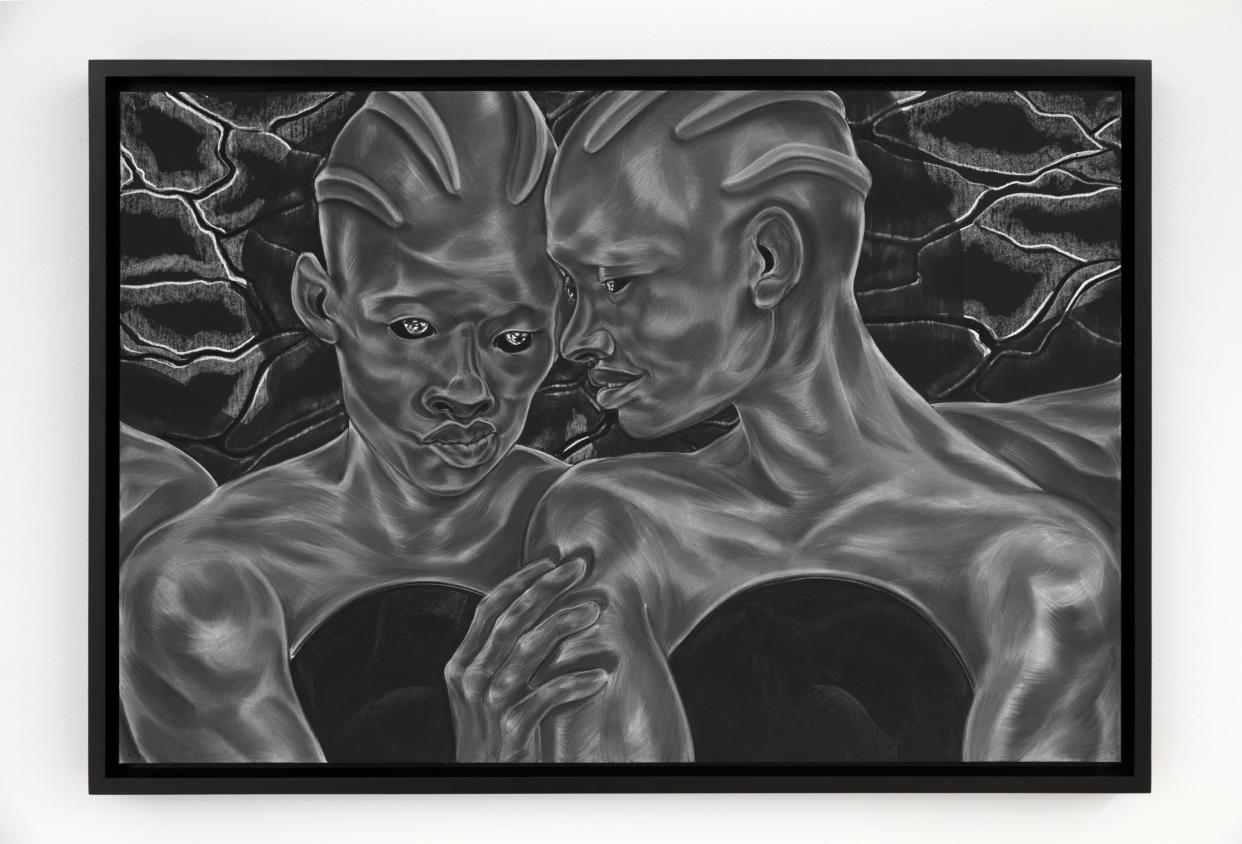

The show, A Countervailing Theory (referring to the idea of “countering an existing power with an equal force”), comprises 40 monochrome drawings, many at large scale, and a multi-layered, atmospheric soundscape, Ceremonies Within, by Peter Adjaye, responding to and enhancing their drama. Ojih Odutola, who counts film storyboards and graphic novels among her disparate influences, constructs a fictional framework for the drawings, positioning herself as the leader of an archaeological research project, piecing together the meaning of a group of “peculiar pictographic markings”.

These, we are told, relate to the social practices of an ancient prehistoric civilisation located in the Jos Plateau, Nigeria, led by women who rule over male labourers — a hive of queens leading a docile underclass of drones. Each group is forbidden to engage in emotional or sexual relations with any but their own gender (no wonder the civilisation didn’t last) — the images tell of the consequences of crossing that line. But of course, as with all ancient discoveries, the narrative is incomplete. The drawings displayed in the gallery are, it says, “life-size scans” of the surviving sheet rock artefacts shown “in the order we intuited was intentioned by their makers”.

This is our position at the start of the show. It’s only by reading the publication (which includes an essay by Zadie Smith, whose portrait Ojih Odutola recently painted for the National Portrait Gallery) that you discover the protagonists’ names — Akanke, one of the Eshu, the female ruling class, and Aldo, one of the male Koba — and that the Koba are created rather than born, to serve a purpose. This process is shown in one of the first drawings, where a line is etched into Aldo’s body by an Eshu. I thought at first it was a tattoo — the women are unmarked, the men all have these sinuous, serpentine seams. But you quickly get the measure of the status quo — the Koba keep their eyes down, are nude and obedient, while the Eshu stand like Spartans, exuding a supreme, casual confidence as they lean on their weapons, dressed in what look like extremely practical clothes for this weather.

I couldn’t help marvelling at Ojih Odutola’s perceptive decision that women of action would, under a feminised power, wear something that closely resembles an expensive sports bra. Anyway, it’s a dramatic switch from the way both genders are usually portrayed in art.

Ojih Odutola knows how our imagination works. You see a scene, a synapse is fired, your mind creates a story. As you walk through this show, trying to make sense of the images conjured by the artist’s pencil (and speaking of the draughtsmanship, the feathered strokes with which she evokes muscles rippling beneath skin, or the burnished shine of that skin under an unseen sun, or the wonderful, textural landscapes that, to me at least, evoked the fynbos of the Western Cape in South Africa, are worth lingering over) you write your own narrative. Are they dancing, or exercising? Fighting or f***ing? It’s frustrating, like hearing a tantalising snatch of conversation in the street, but exciting too. And sobering.

Ojih Odutola reveals to us from inside our own heads that a story — or history — can only ever be perceived, as opposed to known, even by those who are in the thick of it. I found it impossible not to think, afterwards, of the current debates about the need for a wider retelling of Britain’s colonial history, or reports of at-a-glance assumptions made about black people driving nice cars. By making us understand how hard it is to grasp the meat of a fractured narrative, Ojih Odutola reminds us that one viewpoint is not enough.

A Countervailing Theory is at the Barbican Curve, EC2, until August 30

Yahoo News

Yahoo News