Criminal intelligence agency warned it may seek to suppress parts of report on failed project

Australia’s criminal intelligence agency warned the auditor-general that it may seek to suppress parts of his report on its failed biometric identification project, which was dumped after cost overruns and delays.

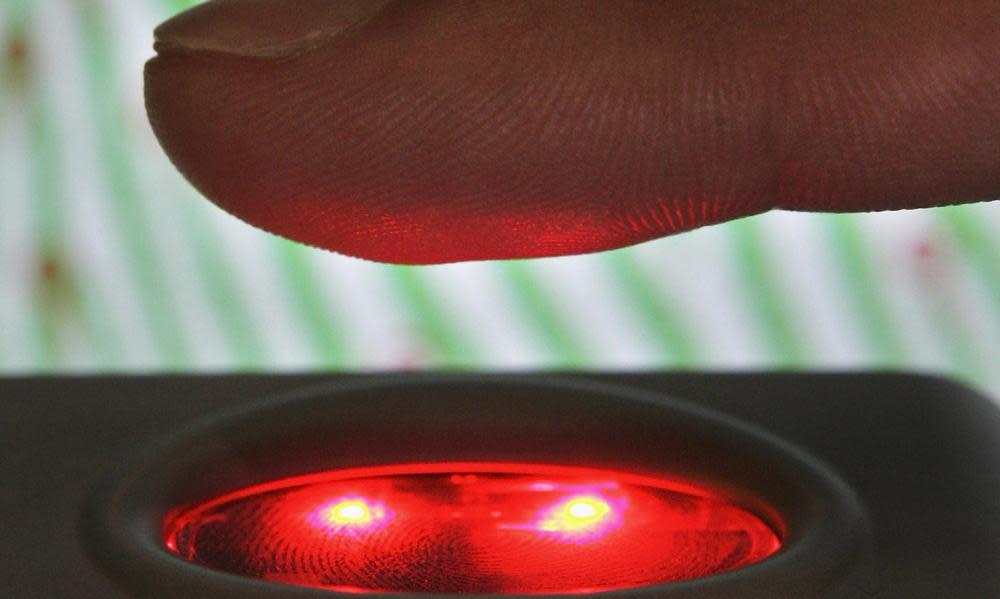

The $46.8m project was handed to technology company NEC Australia by an ACIC predecessor, Crimtrac, which wanted to expand Australia’s existing fingerprint database to include palm prints, foot prints and facial recognition data.

But ACIC was forced to abandon the project in June after huge delays and a reported cost blowout of tens of millions of dollars. To work out what went wrong, ACIC referred the botched project to the auditor-general in February, asking that he investigate whether it was procured and managed appropriately.

Internal correspondence, published on Thursday, revealed that the agency foreshadowed in July that it might make an application to the attorney general, Christian Porter, to suppress parts of the audit.

The correspondence was unclear about precisely which audit ACIC wanted to redact, but the agency confirmed to Guardian Australia that it related to the biometric project.

“The performance audit was initiated at the request of the ACIC,” a spokeswoman said. “The ACIC will not be commenting further on the audit process at this time.”

ACIC’s correspondence came just weeks after Porter used extraordinary powers – for the first time in their history – to suppress parts of a report into the government’s $1.3bn arms deal with multinational arms manufacturer Thales.

Grant Hehir, the auditor-general, has previously warned that the Thales case might set a precedent that other agencies would follow to suppress his work.

In the correspondence, ACIC chief operating officer Paul Williams told the auditor the agency might need to ask for the report to be suppressed if it contained sensitive information.

Williams said one of the agency’s considerations was to protect sensitive data that may be included “inappropriately”: “Looking to the end of audit draft report process (s19 of AG Act) where comments can be made and if sensitive material is included inappropriately, consider applying to the A‐G [attorney-general Christian Porter] for a s37 certificate.”

Section 37 of the auditor-general’s act allows Porter to redact audit reports on a series of grounds, including to preserve national security.

“I reiterate, this is not a matter of obstructionism – it is just us exercising our responsibilities so far as the protection of our data is concerned,” Williams wrote to the auditor’s office.

The audit is due to be tabled in December. Hehir has used various forums – a parliamentary inquiry and Senate estimates – to point out that he regularly dealt with sensitive information involving defence and law enforcement. He said he had rigorous processes to ensure the Australian National Audit Office did not compromise national security or publish sensitive information.

Porter said on Thursday that he was yet to receive any further applications to suppress audit reports.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News