Crisis for Areva's La Hague plant as clients shun nuclear

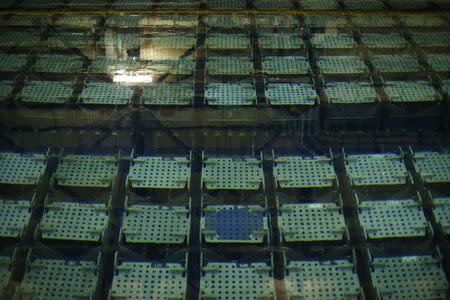

By Emmanuel Jarry BEAUMONT-HAGUE, France (Reuters) - Areva's nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in La Hague needs to cut costs as its international customers disappear following the Fukushima disaster, and its sole remaining big customer, fellow state-owned French utility EDF, pressures it to cut prices. Located at the westernmost tip of Normandy, La Hague reprocesses spent nuclear fuel for reuse in nuclear reactors and is a key part in Areva's production chain, which spans uranium mining to fuel recycling. Its valuation and outlook are crucial for the troubled French nuclear group, which is racing to find an equity partner after four years of losses have virtually wiped out its capital. "Our ambition is to cut costs by more than 15 percent over five years," La Hague director Pascal Aubret told Reuters. Areva said in January it would have to cut about 100 jobs at La Hague, which employs 3,100 people, plus another 1,000 Areva staff working for other Areva units and some 1,000 contractors. The La Hague plant is also planning more separate savings, part of a company-wide plan to cut costs by one billion euros by 2017. One of the world's biggest nuclear waste storage facilities, La Hague's four pools hold the equivalent of about 50 reactor cores under four metres of water. Protected by 1.5 metre thick anti-radiation concrete walls, employees in space suits cut up spent nuclear fuel rods, extract uranium and about one percent of plutonium, and melt the remaining waste into glass for eventual deep storage. Areva says reprocessing reduces natural uranium needs by 25 percent but opponents say that separating plutonium from spent nuclear fuel increases the risk of nuclear proliferation. The United States does not reprocess its nuclear fuel, but Britain has a large reprocessing plant in Sellafield. A planned recycling plant in Rokkasho, Japan - modelled on La Hague - has been plagued by problems and is years behind schedule. Since the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Areva's reprocessing unit has lost nearly all of its international customers. The company's "back-end" sales - which include reprocessing, logistics and decommissioning - have fallen to 1.53 billion euros in 2014, 18 percent of Areva's turnover, from 2 billion euros, 30 percent of nuclear revenue, in 2004. EDF SQUEEZE In the past decades, more than 32,000 tonnes of spent nuclear fuel has been reprocessed at La Hague, of which nearly 70 percent for EDF, 17 percent for German utilities, nine percent for Japanese utilities and the rest for Swiss, Belgian, Dutch and Italian clients. This year, La Hague expects to treat 1,205 tonnes of spent fuel, of which just 25 tonnes will come from abroad. That leaves Areva with EDF virtually as its sole customer, and although both firms are state-owned - Areva 87 percent, EDF 85 percent - EDF has played hardball in contract negotiations. La Hague extracts plutonium from used nuclear fuel, which it then sends to Areva's Melox plant in southeast France, which produces MOX fuel - a mixture of plutonium and spent uranium - for 22 (soon 24) of EDF's 58 reactors. The arrival of new management at both companies since the start of the year has ended years of hostility between France's two nuclear champions, but a 6.5 billion euro contract to treat and recycle 1,100 tonnes per year of EDF's spent fuel for the 2013-2020 period has still not been signed. Union sources and local socialist parliament member Geneviève Gosselin-Fleury told Reuters that EDF wanted Areva to treat the 1,100 tonnes/year for the same price it treated 950 tonnes/year under the previous contract. In its 2014 earnings statement Areva said that "commercial concessions" given to EDF had forced it to take a 105 million euro writedown on its La Hague and Melox plants. La Hague director Aubret said the reprocessing contract was a key element in talks with EDF, which is considering taking a stake in Areva's reactor business. But he added that alongside its cost-cutting plan, Areva aimed to double its investment in La Hague to 200 million per year for nearly 10 years in order to renew ageing equipment and boost capacity of its nuclear waste storage pools. The plant also hopes to attract new foreign clients, notably South Korea, which has a growing nuclear industry but is not allowed to have its own reprocessing installations under a U.S.-Korea treaty. (Writing by Geert De Clercq; Editing by Sophie Walker)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News