Cuts may leave NHS short of 70,000 nurses, leaked report warns

The NHS could be short of almost 70,000 nurses within five years, according to a leaked copy of the government’s long-awaited plan to tackle the staffing crisis.

Blaming the government’s decision to abolish bursaries for nursing students, a draft of the NHS people plan says: “Our analysis shows a 40,000 (11%) shortfall [in the number of nurses needed in England] in 2018-19 which widens to 68,500 (16%) by 2023-24 without intervention, as demand for nurses grows faster than supply.”

That would mean that the NHS’s shortage of nurses increases from one in nine of the workforce to one in six, adding to the rising pressures on hospitals, GP surgeries and mental health care.

The report, seen by the Observer, makes clear that the shortage could be even higher than 68,500 because of “additional pressures” on GP surgeries, which are due to take on greater responsibilities for patient care over the next few years under the NHS long-term plan.

The document adds that even if its recommendations are implemented in full, the health service will still be short of 38,800 nurses by 2023-24, almost as many the current total of 40,000 vacancies. It says: “We believe we can reduce the gap between supply and demand to 38,800 (10%) in 2023-24, assuming that we are able to make progress on all of the interventions in this chapter.”

The workforce strategy was drawn up by senior NHS executives led by Baroness Harding, the Conservative peer who chairs the regulator, NHS Improvement. Ministers hope it will find a way for the health service in England to deal with its growing workload at a time when it is struggling with more than 100,000 vacancies including GPs, nurses, paramedics and psychiatrists. Shortages of almost every type of health professional are leading to the temporary or permanent closure of units providing A&E care, maternity services and chemotherapy.

The plan says George Osborne’s decision in 2015 when he was chancellor of the exchequer to stop paying nursing students’ tuition fees and maintenance grants has led to a huge drop in those applying to be nurses at the same time as the NHS is facing its most debilitating shortage of them in decades.

It says: “Applications for nursing and midwifery courses have fallen since the education funding reforms, with a 31% decrease between 2016 and 2018.” It says the decline has affected all branches of nursing, although the 50% fall in applicants for learning-disability nursing since 2016 is particularly severe. It has also led to “significant” falls in the number of mature students (39%) and men (40%) applying.

Osborne was warned that his decision would backfire but insisted that scrapping long-established subsidies for nursing students would somehow increase numbers and pressed ahead regardless. Until 2016 anyone doing a nursing degree in England had their tuition fees paid in full and received means-tested maintenance grants of up to £3,191. In contrast, the number of student nurses has risen in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, which retained those incentives.

Scrapping bursaries had proved very damaging and they should be reinstated, the Royal College of Nursing said – a suggestion the document does not address. “Already faced with a dire shortage of staff, ministers compounded the problem by pulling the rug from under tomorrow’s nurses. The false economy of removing that bursary slowly dawned on ministers and the NHS. If they want to stop the nurse shortage spiralling further, there is no alternative to returning the £1bn that was taken away”, said Donna Kinnair, the RCN’s chief executive.

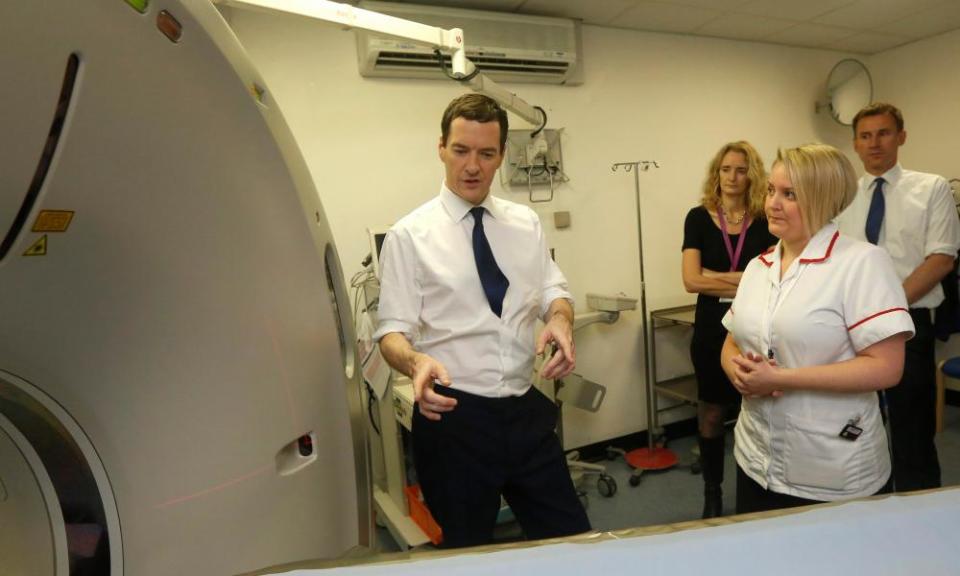

George Osborne visiting Homerton hospital in London when he was chancellor in 2014.Photograph: Luke MacGregor/PA

“There is nothing more devastating for a nurse than not being able to give top-quality care to patients. But in these times of severe shortage, nurses are forced to rush difficult conversations or give drugs later than needed. Despite staying behind for free after a long shift, they still can’t get everything done and important things can be missed.”

The report also warns that government plans to increase the number of homegrown doctors by 1,500 are inadequate, and that a much bigger increase is needed. “We estimate that we need a further initial expansion in the range of 1,000 to 1,500 new undergraduate medical places, but we will clearly need to keep this under review”, it says.

Ministers announced in 2017 that medical school training places would be expanded by 1,500 to create the biggest-ever rise in UK-trained doctors. But the first of them will not be ready to work until 2025 and the health service is struggling with over 9,000 vacancies for doctors.

The document, called the Interim NHS People Plan, has been delayed amid tensions between its authors and the Treasury. Ministers there are unhappy that it includes a commitment that the government will hold a “review” of pension tax rules which are leading doctors to either reduce the amount of work they do for the NHS or retire early.

“Workforce pressures are a fundamental threat to the future viability of the NHS. Frontline trusts have been warning about this growing problem for years”, said Saffron Cordery, deputy chief executive of NHS Providers, which represents health trusts. “Now, at last, we are starting to see a coherent and coordinated approach that acknowledges the urgency of these challenges, and presents some practical steps forward, particularly in addressing the problems we face with nursing shortages. It’s just a start, but it’s a good one.”

Ruth May, chief nursing officer for England said: “The interim plan to be published shortly will focus on how to make the NHS a great place to work, supporting career development and creating a culture to attract, and retain staff. It is also critical we recruit more nurses for the future which is why we’ve already secured 5,500 extra clinical placements for undergraduate nurses which should translate into thousands more student nurses later this year.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News