Dan Gurney: Legendary American racing driver and motor sport innovator

Dan Gurney, who has died aged 86, was one of America’s finest racing drivers, and the first competitor to win in Formula 1, IndyCar and Nascar.

Gurney was also a constructor, of his famed Eagle cars and Alligator motorcycles, an innovator and a campaigner. Without his courage, commitment and talent in the immediate aftermath of Bruce McLaren’s death on 2 June 1970, the famous F1 team might never have survived their darkest hours.

Gurney was born in Port Jefferson, New York. When his father retired as an opera singer the family moved to California, where Gurney developed an interest in Bonneville drag racing. It positioned him perfectly to make his name in west coast sportscar racing, most notably with Frank Arciero’s 4.9-litre Ferrari.

“There were relatively few Ferraris around the world at that stage,” he explained, “so I was able to draw some attention through entrant Luigi Chinetti that led to me being asked to try out for the Ferrari factory. My first Formula 1 race I was sitting there at Rheims with no more than 22 races completed…”

In only his second grand prix, on the banked Avus in Germany, he finished second to team-mate Tony Brooks, and ahead of fellow stablemate Phil Hill. Then he took third in Portugal and fourth at Monza, and he and Brooks shared fastest lap in their Ferrari Testa Rossa in the Goodwood Nine Hours.

For Gurney, Ferrari were just the start, though bad luck meant he often left a team just when they came good. In 1960, he left Ferrari for a disastrous year with BRM. He left BRM to join Porsche for 1961, only to see Phil Hill win the world championship with Ferrari in 1961, and Graham Hill do likewise with BRM in 1962. But in that latter season Gurney scored his first grand prix win for Porsche, before joining Jack Brabham’s new team for 1963. There he established himself as Clark’s strongest rival, winning in France again, and Mexico, in 1964, while becoming known as a front-running driver who suffered appalling luck.

In 1966 he went his own way, with his own glorious Weslake V12-engined Eagle grand prix car, just as Brabham embarked on two title-winning seasons. But he remained philosophical, acknowledging that he wanted something more that just to race for other team owners. And he took huge delight in winning the non-title Race of Champions in his Eagle in March 1967, and then the Belgian GP at Spa-Francorchamps in June, a week after he and Texan AJ Foyt had driven a factory Ford MkIV to victory in the Le Mans 24 Hours endurance classic. He sprayed victory champagne, soaking Ford top brass in a celebratory display of elation that was the first of its kind.

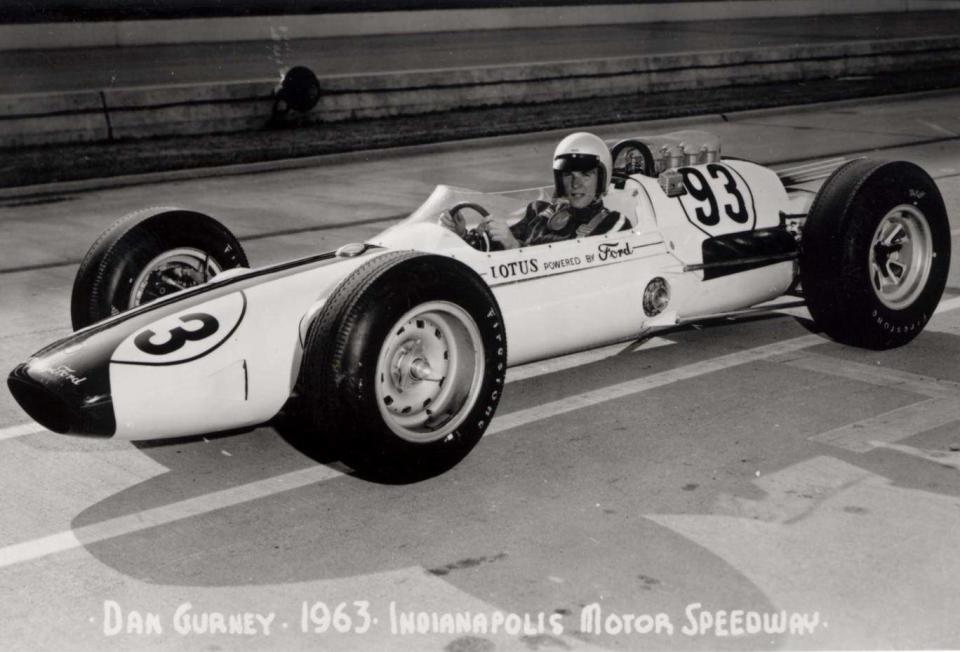

He raced regularly in the Indianapolis 500 from 1962-1970, and it was at his urging that Colin Chapman, Lotus and Ford got together there to exploit the rear-engined revolution that led directly to team-mate Jim Clark’s victory in 1965. Gurney himself would win seven times from his 28 Indycar starts, regularly dominating his beloved Riverside, east of Los Angeles.

He raced a McLaren in F1 in 1968 and his unexpected return with the team in 1970 came about because of Bruce’s death and an urgent call-up from team boss Teddy Mayer. His three races yielded a strong sixth place in the French GP, and his final world championship point.

But it was his performances in the opening two rounds of the CanAm Championship that were perhaps his finest achievement. The first race fell at Mosport Park in Canada, just 12 days after Bruce’s death. Team-mate Denny Hulme was racing while still nursing burns he had suffered on his hands at Indianapolis, and Gurney had never driven the McLaren M8D before. But he rose magnificently to the occasion and put it on pole position, then won that race and the next, at St Jovite, two weeks later. The victories were exactly the boost that the shattered team needed, and Hulme went on to win the series title.

Bruce’s death, and that of Piers Courage in the Dutch GP in between the CanAm races, weighed heavily on the F1 circus. “I remember my wife Evi and I were talking to Jochen [Rindt] after he won the Dutch GP at Zandvoort,” Gurney said. “He said it was so easy to win races like that, and that he was going to hang in there even though the Lotus was an unknown entity as far as reliability was concerned, and that if he made it to win the World Championship he was going to retire and concentrate on his other businesses.” Rindt died at Monza in September, becoming F1’s only posthumous champion. By then Gurney had made a decision of his own.

“I certainly didn’t feel like I was going to quit driving any more, but I felt as though in order to be satisfied with how well you did you were going to have to spend sufficient time doing it. In the end, if you don’t have 100 percent desire to do that, say you only have 99 or 98, that’s a good enough reason to stop. That’s what happened to me in Formula 1.

“I did those last Grands Prix out of respect for Bruce and because of Denny’s burns. Plus part of stopping was being lonely, because a lot of people I had respect for weren’t there any more, and life was just becoming more and more complicated, having to make some decisions even though I didn’t want to. But in the end, it all boiled down to desire.”

He retired officially from racing on 4 October, 1970, with 37 major race wins to his credit. “You know,” he grinned, “the mind plays fascinating tricks. You forget all the things you’d rather not remember, and just remember all the good things.”

At the height of his fame in the 1960s, Car & Driver magazine started a spoof “Gurney for President” campaign that actually started to gain a little traction, to his amusement. Fans quickly slapped stickers on their rear bumpers, proclaiming allegiance to the cause.

Besides the champagne ritual, in 1968 he was the first F1 driver to wear a full-face helmet, when he donned the original Bell Star at Brands Hatch during the 1968 British Grand Prix. And in 1972 he developed what became known throughout racing as the “Gurney flap”, a 90 degree horizontal lip on the trailing edge of a wing which proved to have such stunningly beneficial effects that it was eventually widely copied in all sorts of categories and remains a key aerodynamic tool to this day.

Eagles continued winning in IndyCars up until 1981, before Gurney withdrew from the series in 1986 and went on to enjoy great success with Toyota in IMSA before returning briefly to Cart/IndyCars as Toyota’s factory team in 1996.

“It’s true that I have gone my own way, but that’s just the way it’s been,” he said, acknowledging that of one of his greatest characteristics was to fiddle endlessly with chassis set-ups. “I think the challenge has always been something that means a lot, and you like to try and do things in a way that’s a little bit out of the ordinary. It’s a lot of fun!”

Later that spirit led him to build the Alligator motorcycle and bring the highly innovative DeltaWing race car to life at Le Mans. More recently, All American Racers have been heavily involved manufacturing the support legs for Elon Musk’s Space-X project.

Gurney was taken ill at Indianapolis while he and his Eagles were being honored in 2015. But he rallied, and while, as Evi Gurney admitted, “he won’t be racing you around the ‘shop!” he was nevertheless still nimble when visitors called, and would frequently pop up at ‘coffee and cars’ events around Orange County.

He never lost his racer’s spirit.

On-track his speed, skill and honourability were outstanding; off-track he was also a gentleman and a sportsman. It was no surprise that he and Clark had such a close relationship that he regarded them as “more than brothers”.

“He and I had a doggone good relationship,” he said, “I held him in the highest regard.”

The feeling was mutual. At Clark’s funeral on 10 April, 1968, James Clark Snr took Gurney to one side and told him that he had been the only rival his son feared. Dan never forgot that remark, the highest accolade anyone could have received.

“I was drowned in tears,” he admitted. “That was very precious to me. I managed not to win a world championship and I didn’t win the Indy 500, so something like that meant a good deal to me, to know that I was held in good esteem and I was considered pretty doggone good by the guys that were running at the time.”

He never sought to brag and would only tell that story to friends, whom he knew would understand what it meant to him in his heart. That told you everything you needed to know about an extraordinary man.

Daniel Sexton Gurney, born 13 April 1931, died 14 January 2018

Yahoo News

Yahoo News