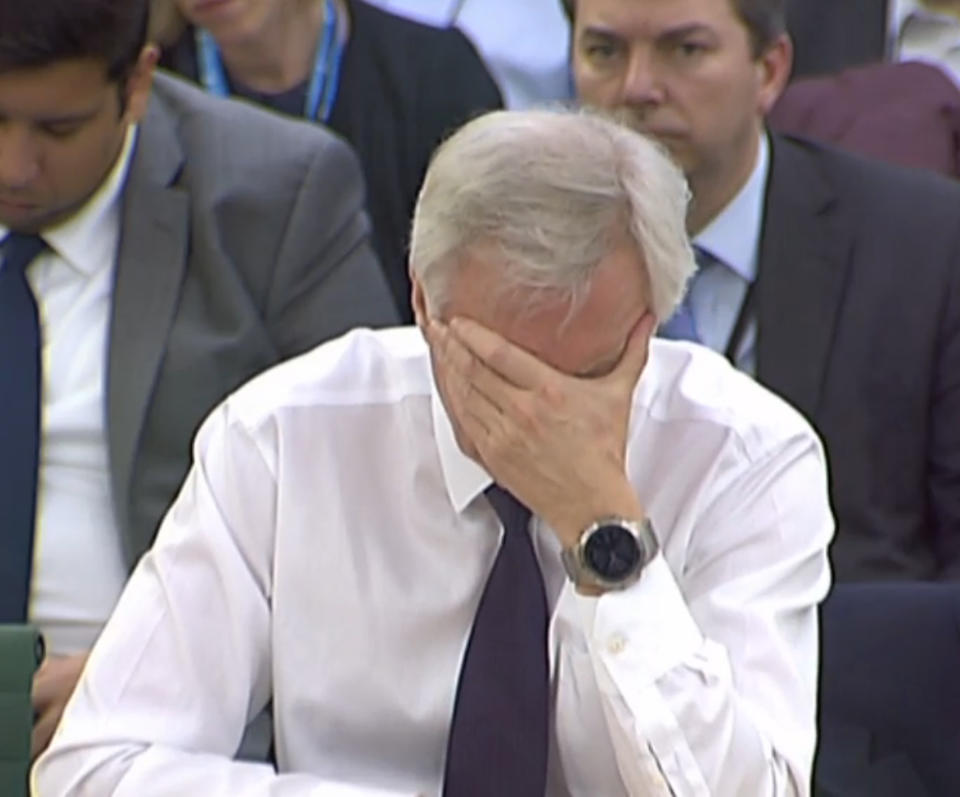

David Davis's supposedly self-deprecating joke was so crushingly unfunny because it was absolutely true

“When I first said I was going to become a comedian, everybody laughed,” said the late Bob Monkhouse. “Well, they’re not laughing now.”

There is nothing quite so perfect as a good self-deprecating joke, for no other reason than modesty is a character trait people tend to like.

Which is precisely why, when David Davis breezily announced on the radio that “I don’t have to be very clever to do my job, I don’t have to know very much,” the only person laughing was him.

This was not, as has been subsequently claimed, a moment of self-deprecation. Davis, a man who exists in a state of permanent self-satisfied intoxication from the aroma of his own farts, is not given to such a thing.

With apologies to the frog that is about to die during the dissection of this particular joke, what so amused Davis here, the root of the joke if you will, was the absurd idea that he might not be very intelligent. That, and I know, I know, it’s ridiculous, he might not know what he’s talking about.

Which isn’t funny, at all, in any way, because it is absolutely true. That Davis was only being interviewed to try to undo the damage from an interview 24 hours before, in which he’d casually mentioned the agreement with Brussels triumphantly announced by his boss on Friday was, in fact, completely meaningless, is something we can come back to later.

First, a brief trot round the paddock of Davis’s Greatest Brexit Hits. 26 May 2016, a month shy of the referendum and the man who would be about to become the UK’s chief Brexit negotiator accidentally made a public declaration of his utter ignorance of how EU trade deals work.

“The first calling point of the UK’s negotiator immediately after Brexit will not be Brussels, it will be Berlin, to strike a deal,” he said, before laying out this utterly deluded plan in glorious detail.

“Post Brexit a UK-German deal would include free access for their cars and industrial goods, in exchange for a deal on everything else,” he said.

“Similar deals would be reached with other key EU nations. France would want to protect £3bn of food and wine exports. Italy, its £1bn fashion exports. Poland its £3bn manufacturing exports.”

Still, we all make mistakes. That a few weeks into the job he declared that the UK would, after exit, have free trade deals ready to sign to create a free trade area “10 times larger” than the single market is also, well, disappointing. At the most conservative estimate, the EU accounts for 20 per cent of global GDP. A free trade area 10 times larger than this would have to incorporate free trade deals with people from other planets, and even with Liam Fox in charge of the process, that seems unlikely.

In February of last year, I had the misfortune of sitting through an hour long David Davis PowerPoint presentation that claimed at one point that 421,000 Spanish jobs are dependent on selling €740m (£568m) worth of Spanish fruit to the UK, which equated to around £1,300 per job at the time. Things may be bad in Spain, but not that bad.

There is a temptation to wonder whether, if David Davis did indeed know anything at all, had burdened himself with even the lightest load of knowledge and information, he might not have been so certain Brexit was a good idea, though it seems unlikely.

We will find out later this week whether the EU27 even agree to formally sign off on Theresa May and Jean-Claude Juncker’s deal, and we move on to the crucial, trade phase of the negotiations. That the UK’s chief negotiator has spent the short intervening days laughing at the agreement and suggesting it will all be chucked out if Britain doesn’t get its own way is a shame.

Just imagine if it were the other way round. If Michel Barnier were to say that, yes, we are moving on to trade negotiations, and if the UK decides it likes what is on offer, we can always stick £10bn or so on the divorce settlement and if you don’t want to pay it then don’t.

On one particularly edifying morning before the referendum, both sides claimed the other was locking the British public in the boot of a car and driving it to a destination it had no control over.

It is hard to avoid the sensation that in Davis, the UK has a driver that isn’t so much lost but has just gone down the wrong slip road, and any attempt to tell him he’s about to pull out directly into oncoming traffic will just be met with the usual unaccompanied laughter.

No one, bar Davis, is laughing now.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News