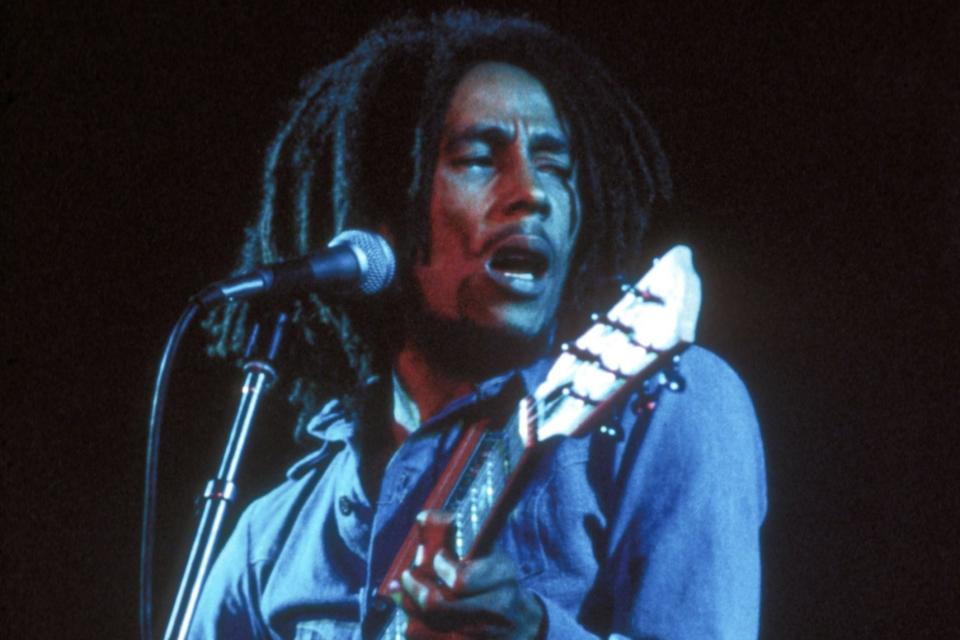

David Olusoga: Bob Marley is getting a blue plaque — who else should?

In the early months of 1977 a journalist interviewed Bob Marley at the west London house he then shared with his band, the Wailers. Speaking about the capital, he told his interviewer: “Me regard London as a second base.”

Across the city are places that are part of Marley’s remarkable story: the clubs where the band hung out with The Clash; Battersea Park, where The Wailers played football; the studios where they recorded. It was while living here that they laid down the Exodus album, featuring two of their most famous tracks, Jamming and One Love.

For Marley, London was a place to have fun, develop his career, record music and meet new people. But in 1977 it was also a place of sanctuary, where he could recover from an assassination attempt that had taken place in Jamaica in late 1976. He had been shot, and one of the things he most liked about the UK capital was that the police did not carry guns.

In a sense, Marley was one of the many thousands who have, over the centuries, come to London and been welcomed as refugees. Some have gone on to have incredible lives and careers — one thinks of the Bauhaus refugees, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy, who were awarded a blue plaque last year at the block of flats in Belsize Park they once called home.

Yesterday English Heritage announced that later this year it will unveil a blue plaque to Marley — one of the first global superstars — at the Chelsea address where he lived. Other plaques slated for 2019 also have global connections.

Archaeologist, traveller and diplomat Gertrude Bell, chiefly known for her role in the Middle East of the early 20th century, will be honoured at what was her family home for 40 years. War correspondent Martha Gellhorn, born in Missouri, had a London base for the second half of her life. And writer Angela Carter, while born and bred in south London, found much inspiration from the time she spent in Tokyo. These three plaques — with thanks in anticipation to the building owners — are the early fruits of an ongoing campaign by English Heritage to increase the number of women commemorated.

The London blue plaques scheme is growing ever more diverse as it seeks to reflect the history of the world’s most diverse city. At the moment, women are commemorated by just 14 per cent of plaques. There are even fewer to black and minority ethnic figures. So there’s much more work to be done. We need more public suggestions for figures of renown or achievement — remembering that to be considered, the person in question needs to be associated with a surviving London building and to have been dead for at least 20 years.

Bob Marley, one of the most recognisable people of all time, is a natural choice and a good start — but his plaque is just the beginning.

David Olusoga is a historian and a member of English Heritage’s blue plaques panel

Yahoo News

Yahoo News