So which decade was better? Battle of the 1960s v the 1980s

Yvonne Roberts

In October 1962 the 60s began for me, in fear and dread. Since the Soviet Union and the US were at stalemate over the Cuban missile crisis, our future was about to be incinerated in a nuclear mushroom cloud. “Girls,” a teacher instructed us 12-year-olds, “in extremis, seek safety under the nearest table.” No, we weren’t convinced either. Survival, the intoxicating awareness that we had been granted a second chance, meant life could only get better. And, for the rest of the decade, it absolutely did.

A year later, in a flea-pit cinema, watching Dr No, the first outing for James Bond, we gawped as Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress), dagger in the belt of her white bikini, rose majestically out of the sea. Who wouldn’t want to be a successful shell diver? Come to that, who wouldn’t want to be 007?

Most of our mothers had been set on a traditional trajectory, women’s lesser paid work, the interruption of war, then careers forfeited once they married. For an increasing number of their daughters (and sons), there was entry into newly built redbrick universities, no fees, generous grants. It was a time when social mobility had yet to receive its requiem. Working class meant a passport to stage, film, music (all of the above, for instance, encapsulated in Alfie starring Michael Caine, written by Bill Naughton, the theme tune a hit for Cilla Black). Youth was shorthand for talent, energy, wit and a healthy disrespect for everything that had gone before based on class, privilege and tradition.

It was a decade of change and more change. Tolerance and opportunity was the mantra. Some of the older generation mourned the loss of deference, the alleged sexual excess of the young, the length of hair, the bottom-wrapping mini-skirts. And, that we refused to know our place.

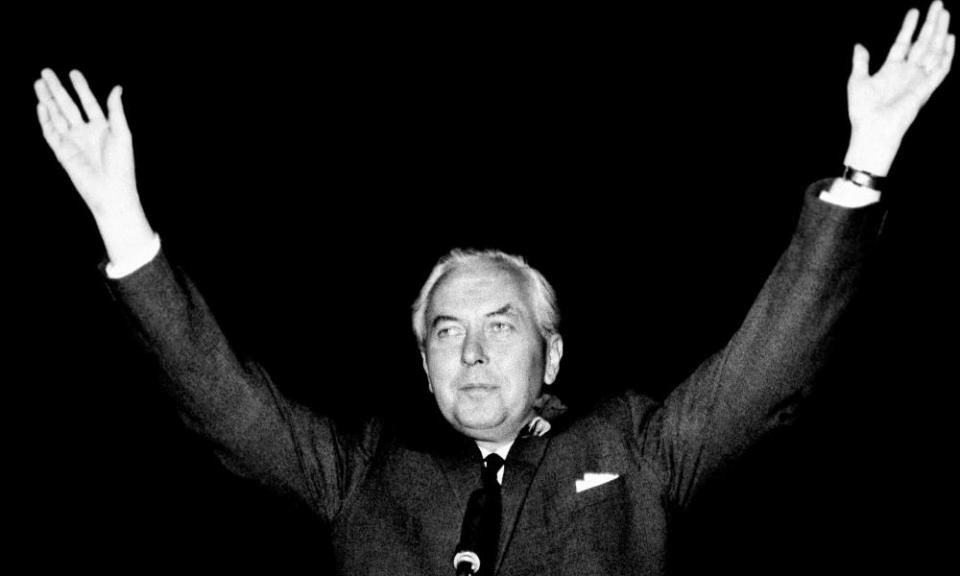

Photograph: AP

“All across the nation/ such a strange vibration/ people in motion,” sang Scott McKenzie. It was a decade born of hope, driven by the thrum of rebellion and carried forward by the conviction that society could and would be different.

It wasn’t just that the young, beginning in the 50s, were visually so different from their forefathers – different hair styles (Vidal Sassoon replacing the tight-crimped perm), different fashion (Biba or, for those with flash cash, Mary Quant) and make-up (fake lashes à la Twiggy; mascara, like Mick Jagger, for the boys), it was that social upheaval was evident in every part of society. Where it would end, nobody knew but it was what was shed that mattered.

In 1964, led by Harold Wilson, Labour won power with MPs who still knew what earning a living with your hands meant. Two years later, Labour won again with a landslide vote. Abortion became easier, as did divorce. Capital punishment ended, homosexuality was decriminalised. The cachet of being a toff was devalued. People could breathe.

It was a decade born of hope, driven by the thrum of rebellion and carried forward by the conviction that society could and would be different

And not just in the UK. In France in 68, the students took to the streets and Charles de Gaulle, the president, took to his heels. In the US, the anti-Vietnam war movement, the fight against racism and the birth of women’s liberation gave a monumental push to human rights. And while there have been many stumbling steps back – many during Margaret Thatcher’s 80s – some of the gains will never be lost. But what of Pattie Boyd’s 80s?

Much of the decade I can’t recall, lost in a fog of paid work, pregnancy, parenting and broken sleep – but I did report on the rise of the new romantics with Steve Strange and Co gravitating from London’s Blitz wine bar to the then Camden Palace. It was a decade of glamour and inventiveness but only as a tinsel distraction from the grim destruction and divisiveness on which Thatcher’s neoliberalism thrived and prospered.

In 1968, at the end of my first year at Warwick University, I travelled to San Francisco, the trip, a three-month Greyhound bus ticket and a semester at Tulane University, New Orleans, all paid for by the state. I visited the home of Flower Power, “tune in, turn on, drop out”, Haight-Ashbury. What I saw was horrendous addiction, homeless teenagers and lost dreams.

The blaze that was the 60s was already dying.

Barbara Ellen

All hail Pattie Boyd for sticking up for the big-haired, greedy, problematic, messy, but also glamorous, go-getting, naughty, diverse, and subversive cultural melting pot of the 1980s.

Parking my childish distaste for 1960s hippy culture for a moment (lank hair, tie-dye, the constant drawling of “ma-aan!” … sorry, no!), it’s undeniable that the 1960s were full of seismic socio-political change, cultural innovation, sexual revolution, and rocket-fuelled social mobility. Thing is, so was the 1980s: they just hid it well.

To paraphrase the little girl in the poem: when the 1980s were good, they were very, very good, but when they were bad … oh dear. Margaret Thatcher, millions on the dole, women with stiff hair-don’ts and quarterback-style shoulder pads; men in Tie Rack braces, snarling “Greed is good” into brick-sized mobile phones. Yet, among the 1980s cliches and casualties, not to mention the excluded (as with the 1960s, a fair few were too beleaguered, broke, or provincial to participate), it’s clear that TV shows like Stranger Things don’t get set in this decade because it was boring.

I started the 1980s as a schoolgirl and ended it not far off from motherhood, so feel free to factor in the rosy-coloured specs of youth and freedom. Still, what a mind-melt of an era, and, unlike the occasionally po-faced, preachy 1960/70s, this decade got the joke about itself even as it was happening.

There was darkness, hardship, rage, misery. On the other hand: glasnost, the fall of the Berlin wall, ambition, opportunity

There was darkness, hardship, rage, misery: Aids, the miners’ strike, the Falklands war, the Chernobyl disaster, the stock market crash. On the other hand: glasnost, the fall of the Berlin wall, ambition, opportunity. Also, for someone my age, a veritable glut of youth tribes and movements: post-punk, anarcho-punk, new romantic, futurist, goth, indie, dance, house, hip-hop, club-kid, electronic, crusty, soul, rave, metal, grebo, take your pick.

Yes, Kylie and Jason (and why not?), but also Madonna, Prince, Jesus and Mary Chain, New Order, Soft Cell, Public Enemy, Pet Shop Boys, Crass, Mary Margaret O’Hara, Bananarama, KLF, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the Sugarhill Gang, Happy Mondays, Stone Roses, Beastie Boys, a pregnant boogying Neneh Cherry, the Sugarcubes, Nirvana, Salt N’ Pepa, Soul II Soul, and too many more to list here. The decade that good taste allegedly forgot also gave us Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love, David Bowie’s ongoing dominance, and the beginnings of rave/acid house culture.

Indeed, far from being an era of vandalism-cum-philistinism, the 1980s had a vast cultural wingspan: alternative comedy; the Young British Artists; the rise of feminists such as Andrea Dworkin and Bell Hooks; a robust magazine culture and a thriving fanzine counterculture. Elsewhere, films: Wall Street, but also Betty Blue, The Shining, Spinal Tap, The Breakfast Club, Blue Velvet, Mississippi Burning. Television: Dallas and Dynasty, but also The Tube, The Comic Strip, The Young Ones, Boys From the Black Stuff. Fashion: ra-ra skirts and (mercilessly studded) “bodies”, but also Katharine Hamnett and Pam Hogg. Literature: everything from The Handmaid’s Tale to The Satanic Verses to The Color Purple to Slaves of New York.

Moreover, a young person could “do” the 1980s on the cheap. The student grant system still existed. Hitching was stupid and dangerous (don’t do it, kids), but it got you around for free. Squatting and dole culture proved to be undersung incubators for future talent.

Put like this, the 1960s, albeit trailblazing, could almost seem a little (whisper it) one-note. Of course, it’s all cultural apples and oranges. Most people tend to have a big squidgy soft spot for the era of their extreme youth, and we’re all entitled to our memories, whether they’re Mick Jagger strutting at Hyde Park, or carefully crimping hair (darlings, there was an art to it) to the strains of Soft Cell’s Bedsitter.

Even at its most ridiculous and excessive, I now view the 1980s as you might a brash friend who can’t resist showing off: “Look what I’ve got! Look what I did.” In the end, the 1980s could be tough, cruel, stultifying, seditious, combative, glamorous, decadent, and everything in-between – but, to hijack the Pet Shop Boys lyric, it was “never being boring”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News