Deported gay Afghans told to ‘pretend to be straight’

Gay Afghans can be deported to their home country, where homosexuality is illegal and “wholly taboo” and they must pretend to be straight, under new British government guidelines for handling asylum applications.

The new guidance for a country where not a single citizen lives an openly gay life has been denounced by human rights groups as a violation of international law, and criticised by the Home Office’s own Afghanistan unit.

“The Home Office’s approach seems to be to tell asylum seekers, ‘Pretend you’re straight, move to Kabul and best of luck,’” said Heather Barr, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Living a life where you are forced to lie every day about a key part of your identity, and live in constant fear of being found out and harassed, prosecuted or attacked, is exactly the kind of persecution asylum laws are supposed to prevent.”

The document, dated last month, clearly lays out the multiple risks to LGBT Afghans from their own families, from Afghan laws, and from Taliban insurgents who consider homosexuality a crime punishable by death.

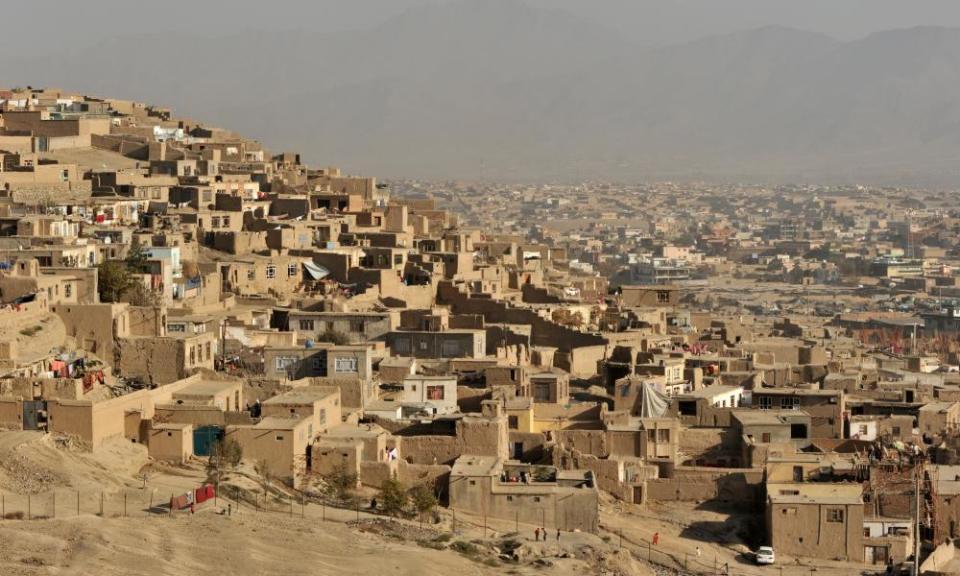

It also suggests that lesbians and gay men “with what may be seen as feminine traits” would be at serious risk if forced to return. But the guidance goes on to argue that as the Afghan government has not recently prosecuted anyone for homosexuality, and the Taliban do not currently threaten the capital, a closeted gay Afghan could live safely in Kabul.

“While space for being openly gay is limited, subject to individual factors, a practising gay man who, on return to Kabul, would not attract or seek to cause public outrage, would not face a real risk of persecution,” the document says. “In the absence of other risk factors, it may be a safe and viable option for a gay man to relocate to Kabul, though individual factors will have to be taken into account.”

This apparently puts the Home Office at odds with United Nations guidelines on refugees, which specify that LGBT people should not be required to change or conceal their identity to avoid persecution, said Paul Twocock, director of campaigns, policy and research at Stonewall.

“These Home Office guidance notes on Afghanistan seem to directly contradict this. They openly acknowledge that LGBT people are at risk, but also state that they can escape persecution if they are careful not to attract attention by hiding who they are,” Twocock said.

“This is unacceptable and leaves LGBT people in danger. We strongly urge the government to change its approach.”

The Home Office’s own Afghanistan unit expressed deep concerns with the guidance. An attachment to the main document bluntly states “homosexuality remains wholly taboo” in the country and underlines that gay Afghans have to conceal their identity.

The lack of prosecutions for homosexuality since the Taliban were ousted from power in 2001 does not reflect an increased openness, the note continues, just greater respect for the rule of law.

“There is very little space in Afghan society, in any location, to be an individual that openly identifies as LGBT. Social attitudes and the legal position of homosexuality means that the only option for a homosexual individual, in all but the very rarest of cases, would be to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid punishment.”

It also objects to references in the report to the common practice of sexually exploiting young boys. “We are deeply concerned at the suggestion that the prevalence, especially in the Pashtun community, of the practice of bacha bazi [pederasty] implies an acceptance of certain homosexual conduct,” warns the document, signed by the head of the unit.

“Its occurrence reflects Afghanistan’s inability to deal with child sexual abuse and paedophilia. It should not be associated with consensual homosexuality and attitudes towards this.”

The Home Office declined to comment directly on the new guidelines, saying only that each claim is considered on its individual merits, and in accordance with the UK’s international obligations. “Where someone is found to be at risk of persecution or serious harm in their country of origin because of their sexuality or gender identity, refuge will be granted,” a spokesperson said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News