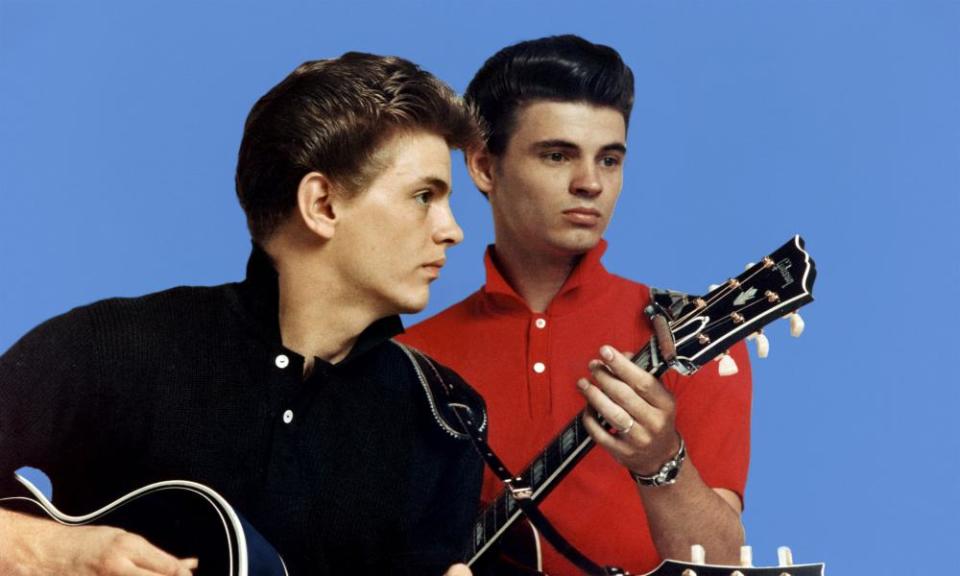

Harmony, melancholy and the Everly Brothers’ indelible influence

Among the hundreds of hours of outtakes from the recording sessions that eventually became the Beatles’ Let It Be album, there is a version of Two of Us, taped on 25 January 1969. As John Lennon and Paul McCartney harmonise, the latter says to the former: “Take it, Phil”, a reference to Phil and Don Everly, the duo upon whom the pair had originally attempted to model themselves. On an early holiday, Lennon and McCartney attempted to impress local girls by telling them they had a band back home and they were “the British Everly Brothers”.

Shortly afterwards, the pair temporarily stopped working on the song entirely and began performing a ragged cover of Bye Bye Love instead. It’s both oddly sweet – a fleeting moment where the ill-tempered sessions actually achieved their aim of returning the Beatles to their roots – and oddly telling. At the end of a decade in which they had done more than anyone to alter rock music entirely, shifting its parameters until it was occasionally unrecognisable from the state in which it had started the 60s – and rendering the likes of Don and Phil Everly old news in the process – John Lennon and Paul McCartney still wanted to sound like the Everly Brothers. Throughout it all, McCartney later wrote, “their music echoed through my mind”.

But then, who wouldn’t want to sound like the Everly Brothers, at least when it came to harmony vocals? Listen to their run of hits from 1957 to 1962 and you hear music that’s both airy and haunting, simultaneously modern and centuries old. The lyrics centre around the rock’n’roll topics of teenage romance and high-school life, but the Everly family had roots in Kentucky, and the brothers’ vocals were similarly rooted in the harmonies of Appalachian folk music. For all the apparent ease with which their voices blended together and the talk of the ineffable power and artlessness of fraternal harmonising, Phil said their singing was a complex, intricate, high-wire act based around diatonic thirds, with his older brother – who tended to sing the leads – very much in charge. “He’s so good, I have to pay attention every second with my harmonies,” he said shortly before his death in 2014. “It’s like playing tennis with someone who is really great. You can’t let your mind wander for a nanosecond.”

It was a sound they could use to conjure up exuberant joy – as on 1959’s (Till) I Kissed You, written by Don – but more often turned to evoking sadness. A deep and affecting vein of melancholy runs through most of their biggest hits. Often heartbroken even when the music was upbeat, as on Bye Bye Love, they excelled at ballads: the otherworldly All I Have to Do Is Dream; the dejected, self-penned Cathy’s Clown. If you want to hear how eerie they could sound, turn to Songs Our Daddy Taught Us, their 1958 album of traditional country – a remarkably bold move at the height of rock’n’roll – and their five-minute-long version of the 19th-century song Lightning Express, its starkness cutting through the song’s tearjerking sentimentality: “The best friend I have in this world, sir, is waiting for me in pain, expected to die any moment.” If you want to hear the unadorned power of their singing, their minor 1959 hit Take a Message to Mary strips down the musical backing until it’s barely there at all: the acoustic guitars are low in the mix, someone clinks a bottle in lieu of drums and everything is focused on the vocals.

It was a sound that seemed to leave an indelible imprint on the subsequent generation of musicians. Quite aside from the Beatles, the Everly Brothers were feted by everyone from the Rolling Stones – Keith Richards hailed Don as “one of the best rhythm guitar players I’ve ever heard” and called their voices “almost mystical” – to the Beach Boys. Paul Simon called them “the most beautiful-sounding duo I ever heard”, Bob Dylan claimed “we owe these guys everything – they started it all”, while Neil Young suggested his entire career was based on trying and failing to sound like them.

Given the degree of influence they wielded, the 60s should have been an easy decade for them to adapt to. They clearly had ambitions that extended beyond rock’n’roll and country – in 1961, Don recorded a big band version of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance under the pseudonym Adrian Kimberly, gamely trying to market it as “The Graduation Song” – and could certainly adapt to changing times: listen to 1966’s Glitter and Gold and June Is as Cold as December, the latter a superb take on the Byrds’ electric 12-string guitar sound. They recorded with the Hollies as their backing band on Two Yanks in England – transforming some minor songs the Hollies contributed with their voices in the process – and Don, always the more outward-facing of the pair, enthusiastically embraced the new era, palling around with Jimi Hendrix and taking LSD.

But the hits stopped. Perhaps they were too linked in the public’s minds to the first wave of rock’n’roll, although a confluence of circumstances – the pair’s increasingly strained relationship; amphetamine addiction that in Don’s case led to a 1962 overdose; a spell in the US Marines – doubtless contributed. The earthiness of the post-psychedelic era, ushered in by the Band’s Music From Big Pink, suited them better: their fantastic 1968 album, Roots, like the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, introduced what became known as country rock. But it didn’t sell, which seems extraordinary when you hear how potent their version of what Gram Parsons called “cosmic American music” sounded on You Done Me Wrong or Mama Tried. Nor did Don’s eponymous 1970 solo album, a true overlooked gem, home to the gorgeous song Omaha.

Related: Sign up for the Sleeve Notes email: music news, bold reviews and unexpected extras

The duo acrimoniously split in 1973, and Don pursued a country career with intermittent success before a high-profile 80s reformation. The subsequent EB84 album, with its contributions from McCartney and ELO’s Jeff Lynne overshadowing a trio of great Don Everly originals, set the tone for the remainder of their career, which was heavy on support from younger artists they had influenced. They sang on Paul Simon’s Graceland, while Simon and Garfunkel made explicit the debt they owed them by bringing the brothers onstage during the first set of their 2003 tour. Among the scattered recordings they made, a 1986 version of Dire Straits’ Why Worry makes the Brothers in Arms album track sound like something Don might have written himself in 1960.

Eventually, their old enmities resurfaced: by the time of Phil’s death in 2014, the pair had become estranged again, this time apparently arguing over US politics. Nevertheless, his brother’s death still poleaxed Don: he kept his ashes and claimed to speak to them on a daily basis. But for all the what-ifs of their post-rock’n’roll career, which left him with a string of early hits and a subsequent back catalogue rich in buried treasure, Don couldn’t help but be aware of the extraordinary influence he and his brother had exerted, because people like McCartney kept telling him.

“If someone comes up and says they were influenced musically by us, and that they appreciate that influence, that makes me feel really good to think that I had influenced people,” he said in 2016. “I don’t take it for granted.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News