DMX’s powerful work confronted an American hell of trauma and poverty

Listening to a DMX song from the late 1990s is like riding a wrecking ball through a gated community. The music video for Stop Being Greedy – one of many confrontational highlights from the rapper’s 1998 Def Jam debut, It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot – shows DMX hunting a wealthy white man across a mansion, before eventually feeding the poor soul like a T-bone steak to his pet pitbull; the rapper’s exhilarating, half-barked vocals gave the sense that he wanted to eat the rich.

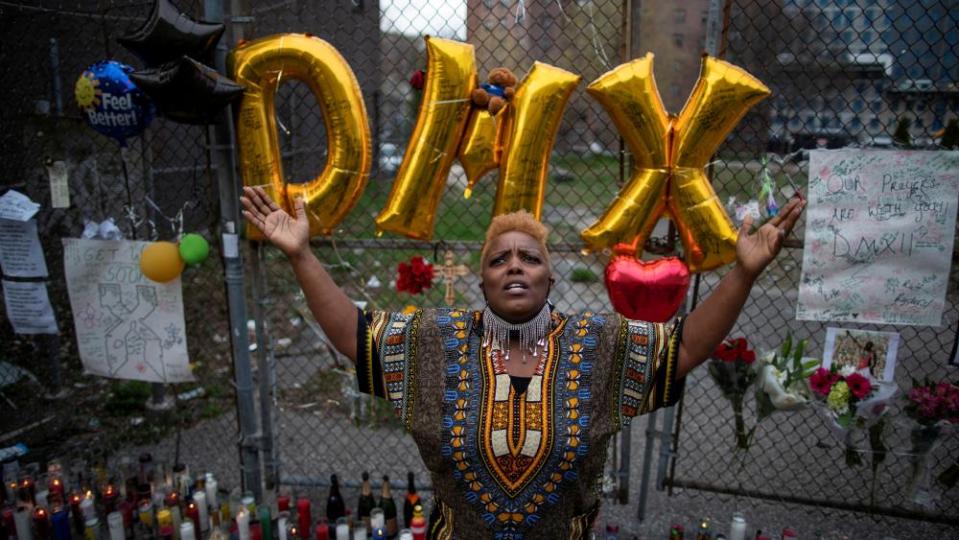

It’s a song about the poor feeling so ignored that they have no choice but to confront the ruling classes (“Ribs is touching, so don’t make me wait / Fuck around and I’m gon’ bite you and snatch the plate”) and violently rip up their rules, and its message reflected an urge by DMX – who died on Friday at the age of 50 – to liberate a hip-hop culture that by 1998 had become too preoccupied with shiny suits in tacky music videos filmed inside a blingy Rubik’s Cube.

Stop Being Greedy was raw like Bad Brains’ Attitude or the Sex Pistols’ God Save The Queen were raw. It was a moment of pure punk defiance that administered CPR to hardcore rap, which was in stasis following the deaths of gangster rap kingpins 2Pac and Notorious BIG. By including at least four other songs (Get At Me Dog, Ruff Ryders Anthem, Fuckin With D, ATF) that could all qualify as rap Smells Like Teen Spirit moments on what was only his first studio album, X cut through MTV-era capitalism with the precision of Candyman’s rusty hook (blood and horror were all part of his work).

It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot and its sadistic yet brilliant follow-up, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, both reached US No 1 in the same year. With these powerful releases, DMX angled the spotlight back to those who had nothing in their pocket. He appealed to the underdogs and those who missed the frenetic, unapologetic energy of 2Pac, but also to white kids from the suburbs who needed a soundtrack for their Mountain Dew-induced temper tantrums. His conversational, often witheringly witty flow shifted from life coach pep talks to grave threats to enemies (“pluck you like a chicken wit’ your head cut off”). The music got bigger and more stadium-friendly as DMX’s career progressed across the 2000s, with urgent bangers such as Party Up, X Gon’ Give It To Ya and Where the Hood At each capable of starting a riot at a house party.

He also translated his magnetic alpha male energy into an underrated film and TV acting career. Whether boasting about being “untouchable” in cult gangster classic Belly, or tenderly dropping speeches about the beauty of growing orchids on the sitcom Fresh Off the Boat, he always lit up the screen.

The reason he barked like a dog in his verses was because angry stray dogs became rare friends during various spells of teenage homelessness; they also became targets of his frustration, with DMX earning convictions for animal cruelty. During his childhood, he said to GQ he was violently abused by his mother (“she knocked two of my teeth out with a broom”), and he never really knew his father. In a 2020 podcast interview with rapper Talib Kweli, DMX cried as he recalled a male mentor tricking him into smoking a joint that was laced with crack cocaine at just 13. It was a life-defining moment.

On the career-best, gothic trap fable of Damien, DMX – who struggled with mental health and addiction issues – scarily switches between his own voice and a demonic monologue. His twisted alter ego represented the pain he carried from this childhood experience, showing a constant conflict between embracing the darkness of suicide and the light of life. His thunderous expression on the mic sounded like a man venting and purging, and these brutally honest sermons gave his fans the strength to move through their own personal traumas (today, this soul-cleansing energy is continued in the US by rappers like Denzel Curry, Rico Nasty and Jpegmafia).

DMX trained his pitbull to bark ad-libs at terrified rivals during freestyle battles, fathered 15 kids, sold 23m records, totalled sports car after sports car, became a sex symbol in muddy Timberland boots, had Jay-Z open for him on tour, created a moshpit that looked bigger than a small country at Woodstock ‘99, and topped the charts with each of his first five albums. He was a force of nature, an all-or-nothing character who could be profound but also self-destructive, moving in and out of prison for petty crimes. Recent studio videos suggested a man more at ease with himself, relaxed and dancing to Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall in between finishing songs for a long awaited new album. His verse on the Lox’s 2020 single Bout Shit was also an undeniable return to form; that growl still blew you off your feet.

Before his tragically early death, DMX endured so many obstacles America threw at him, detailed in his lyrics: “You wanna be me? Here’s what you do / Grow up neglected by both parents and still pull through”. On Slippin, a warm, bluesy piece of self-motivation, DMX said: “To live is to suffer. But to survive, well, that’s to find meaning in the suffering.” It’s a lyric that tells you everything you need to know about the discography of pain and power that Earl Simmons has left behind.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News