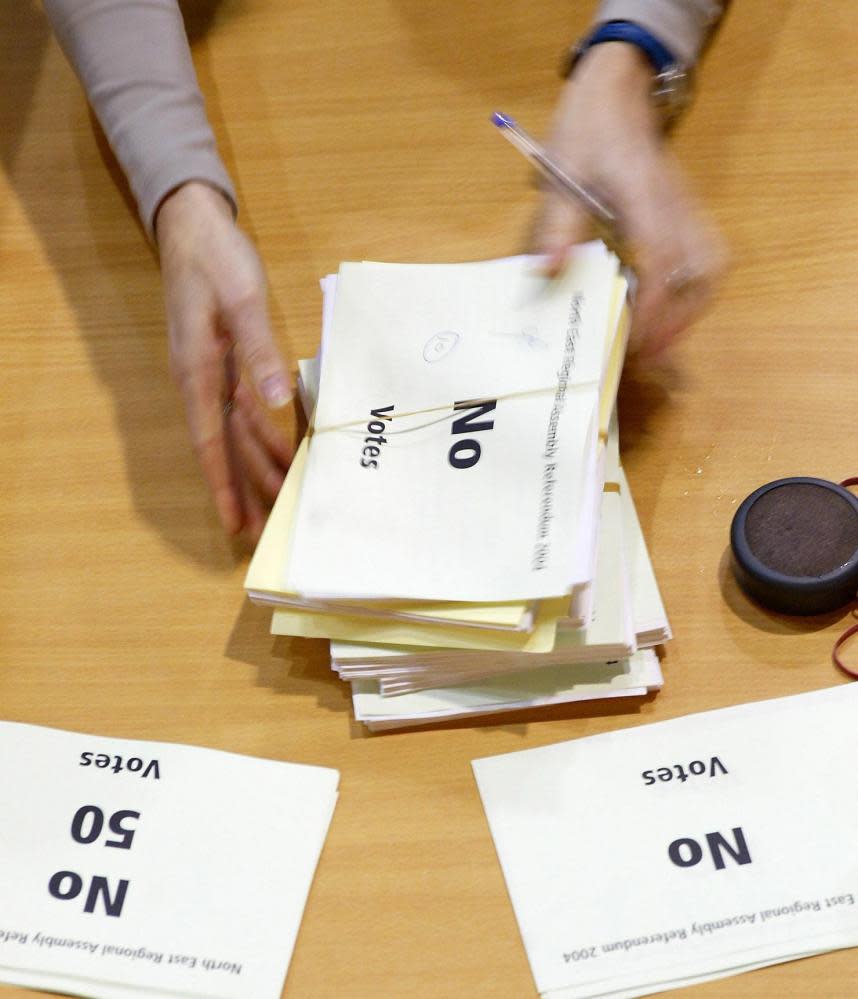

Dominic Cummings honed strategy in 2004 vote, video reveals

A video unearthed by the Guardian from the North East Says No (Nesno) campaign in the north-east referendum of 2004 reveals how Dominic Cummings successfully deployed strategies reminiscent of Vote Leave’s 2016 playbook.

The advert from the “forgotten referendum” not only pits the people against politicians but also pledges to pump millions into the NHS that would otherwise be used to run political institutions.

Cummings, Nesno’s strategic adviser, defeated the then deputy prime minister John Prescott’s plan for regional assemblies by masterminding a campaign that led to a 78% rejection of devolution – despite early polling predicting a 60%-plus victory for the government’s “yes” campaign.

Chief among the lessons Cummings learned from this dry run for the Brexit referendum was that Britain had an appetite for supercharged anti-establishmentarianism. Nesno’s chief spokesperson, Graham Robb, described the operation as “Britain’s first populist campaign”.

Nesno used billboards, stunts and television advertising for a largely negative campaign with the message that a regional assembly would have limited powers and lead to a hike in council tax that would not pay for any additional doctors, teachers or police.

“We did not need a positive message. We were the no campaign. That’s a negative act,” wrote William Norton, Nesno’s referendum agent, recounting a strategy meeting with Cummings.

Norton told the Guardian that Cummings was the campaign’s “messaging person” who coined the slogan: “Politicians talk, we pay.”

That phrase is the centrepiece of the video created by Cummings and Nesno, which was broadcast on regional television in the lead-up to the vote. “The regional assembly would create more politicians, so as you would expect it means the regional assembly will come with huge extra cost. The bill for the north-east would be a staggering £1m per week,” the advert states, followed by the caption: “More doctors, not politicians.”

“The equating of money spent on more politicians instead of doctors resonated,” said Robb, who voiced the video. “It isn’t about, to the penny, what slogan you use about the NHS. It’s about the principle of it.”

In contrast, yes campaigners produced “an upbeat image of the north-east … [which] for all its good intentions and celebrity support did not communicate its vision so clearly”, a UCL report on the referendum concluded.

The effectiveness of populist advertising clearly stayed with Cummings as he plotted Vote Leave’s campaign strategy.

“It was ludicrous to suggest that any additional money spent on a regional assembly could instead have been used to fund more doctors,” said Julie Elliott, Sunderland Central MP and a key figure in the 2004 yes campaign. “Local governments do not have extensive responsibility for medical services.

“But the problem was that once that disinformation was out there, it was impossible to extinguish it in many voters’ minds. We debunked the claim in every town hall meeting around the region but typically only 20 to 50 people would turn up to those and the voting population was 4 million.”

Prescott echoed the sentiment. “[A regional government would cost] £12m less to the people in the north-east. They have said it will be more politicians – it’s 500 politicians less,” he said.

Cummings worked hard to distance Nesno’s campaign from the establishment. “‘Heavyweight’ after ‘heavyweight’ turned up for the yes camp, from Gordon Brown to Charles Kennedy,” he blogged. “They made things worse … in fact they were moving swing voters our way and turning out our vote.”

Instead of celebrities, Nesno diverted its focus to stunts. While the yes campaign unveiled a cultural manifesto which promised more rights for artists, Nesno was burning £1m-worth of fake £50 notes.

In a more recent blog, Cummings reflects on how the strategies he developed for Nesno became the blueprint for the Brexit referendum. “It was a training exercise that turned out surprisingly well. SW1 100% ignored it, thankfully,” he said.

Asked about the Nesno advert, a friend of Cummings said: “This was true, that’s why 80% of the people in the north-east voted no to more politicians and saved themselves a fortune.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News