Dorothea Lange art: Five things you need to know

Dorothea Lange put her lens up to the American dream and discovered a nightmare.

When the stock market crashed in September 1929, the United States became a very different place. The effects were not just felt on Wall Street, but across the country, as the economic decline hit the poorest hardest.

An exhibition of work by Lange, a groundbreaking photojournalist who captured poverty, injustice and disillusionment across the mid-century United States, will open at the Barbican Centre this week.

This is what you need to know about the pioneering photographer who changed the way the world saw America.

Dorothea Lange’s most famous photograph has become a symbol of the Great Depression

During the 1930s, severe dust storms - known as the Dust Bowl - devastated agriculture and forced migrant workers to move across the US in search of work and food. Dorothea Lange captured this hardship with humanity and emotional urgency. Migrant Mother, her most famous photograph, is a portrait of 32 year old Florence Owens Thompson and two of her children in Nipomo, California, 1936. On the search for work, her brow furrowed and her clothes frayed, Lange’s image of Thompson epitomised the situation many American families found themselves in. When the government saw the photographs Lange took in the migrant camp where she met Thompson, the horrendous conditions prompted them to rush aid to the starving inhabitants.

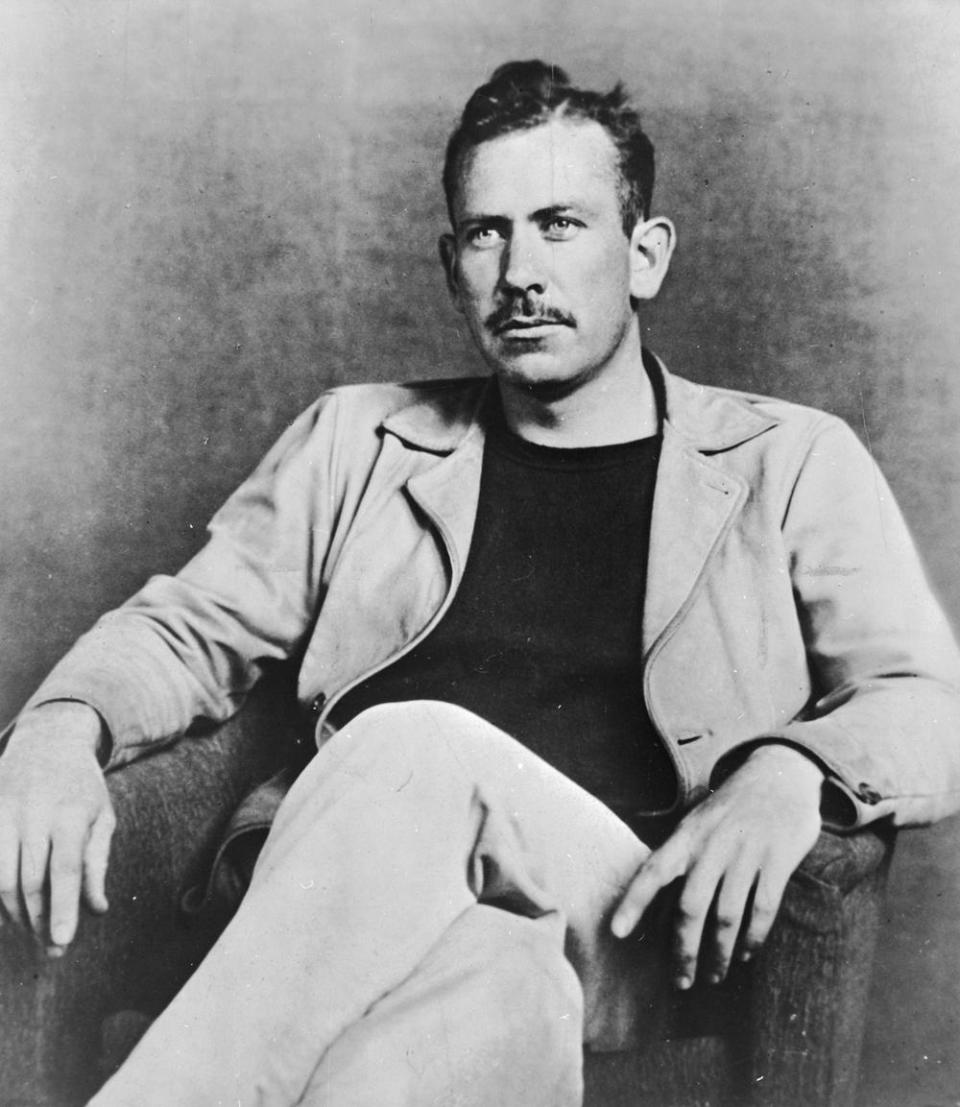

John Steinbeck was a big fan of hers

If it was Dorothea Lange who captured the Great Depression through a lens, it was John Steinbeck who did so through his words. Lange was commissioned by the Farm Security Administration to photograph the struggling farming community, the same subject Steinbeck’s would immortalise in Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath.

Their writing and photographs appeared alongside each other in publications, and her images were studied by director John Ford while working on the film of The Grapes of Wrath. In July 1960, Steinbeck wrote to Lange reflecting on their professional relationship, telling her “There have been great ones in my time and I have been privileged to know some of them and surely you are among the giants... How I wish I may do it as gallantly as you.”

She had polio as a child

Lange was not without difficulties in her own life. Her father abandoned her family when she was just 12 years old, five years after Lange contracted polio at the age of seven. The disease weakened her right leg so severely that Lange would walk with a limp for the rest of her life. This, however, did not stop prevent Lange’s dedicated travels across Dust Bowl stricken states. "It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me," she once said of the affliction. "I've never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and power of it."

She was the first woman to be given a Guggenheim Fellowship for Photography – but she gave it up

As a female photojournalist, Lange was in the minority. Her extraordinary work, however, made her a pioneer of the male-dominated industry, and earned her a Guggenheim Fellowship for Photography in 1941, the first woman to ever hold the accolade. Lange, however, left the position early in order to pursue a project with the War Relocation Authority. The role saw Lange chronicle the evacuation and internment of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast of the US following Pearl Harbour.

Her photos of Japanese-American internment camps were hidden by the Army

Photographing the destitution and desolation of the Dust Bowl was not Lange’s only act against social injustice. In the war years, Lange turned her attention to the internment of more than 110,000 people – including children – of Japanese ancestry. More than half of those incarcerated by the government were American citizens. Lange travelled to Manzanar, the first permanent internment camp, to photograph the situation there. Her critical photographs were later impounded by the army, and were not released to be seen by the public until after the end of the war.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing and Vanessa Winship: And Time Unfolds run at the Barbican Centre from June 22 to September 2 2018. For more information visit barbican.org.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News