Duffy has made peace. But social media won't let her

Duffy’s statement regarding her horrific sexual assault was striking not only for its bravery, but for being so direct. This was a radically unfiltered statement issued not via a spokesperson or PR company, but made, as is now becoming standard in popular culture, via social media.

The utopian ideal of social media platforms trumpeted by CEOs such as Twitter’s Jack Dorsey is that they allow the silent to have a voice, and theoretically this is true. Accompanied by an image she will have chosen herself, Duffy was able to speak plainly of the journey through trauma to self-definition, without her words being filleted by journalists (though they inevitably were in news reports, including by me in these pages).

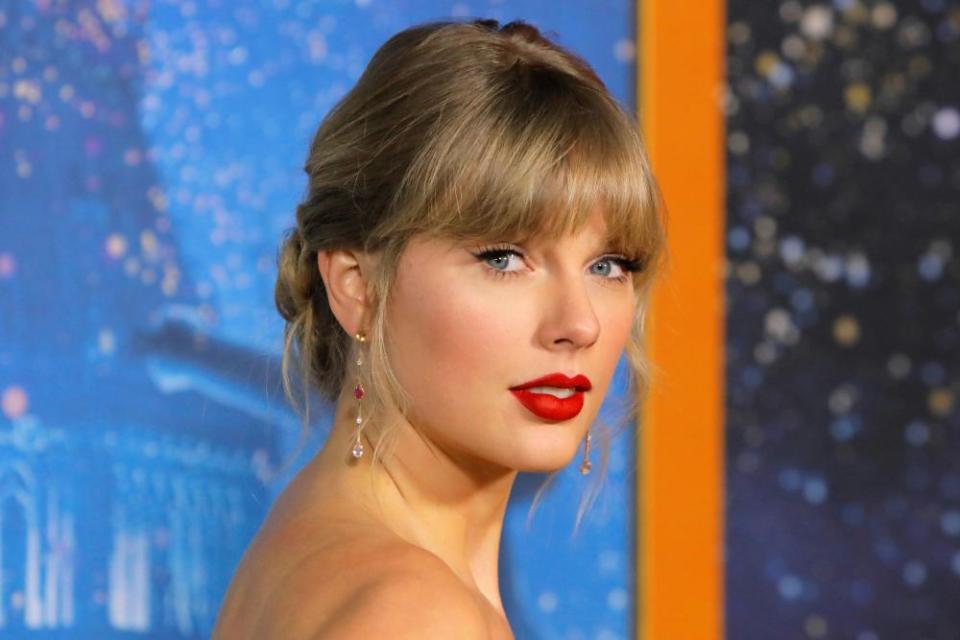

This control stars can ideally have over their narratives is one of the major draws of social media. Hyper-scrutinised pop singers such as Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift do fewer interviews with journalists, instead releasing statements on social media. Last September, Bieber posted a long essay on Instagram about his substance misuse and mental health. Swift, meanwhile, has used her social media accounts as a platform from which to side with the US Democrat party or castigate music mogul Scooter Braun over his handling of her back catalogue.

Social media platforms also offer one of the most coveted assets in pop: authenticity. One of the many appealing things about Ariana Grande is her passionate and witty stream-of-consciousness messages on Twitter, which colours in her personality a handful of characters at a time: she becomes closer, more tangible, and inspires greater adoration in her fans as a result.

But social media aren’t only about standing on a soapbox at the Speakers’ Corner of the internet – they let a crowd of people heckle you, too. Duffy made an extraordinary appeal as part of her statement: “If you have any questions, I would love to answer them.” It is a plea that is touching in its openness to human decency in the wake of her ordeal, but also has the naivety of someone who’s last brush with fame came before Instagram even existed – there have inevitably been trolls making dark jokes in response.

This is the problem with statements like hers: they offer the illusion of control, but the narrative is often wrested away in the tumult of social media, where faith is inherently bad. She has said she will soon post an interview, presumably with the unnamed reporter who she says gave her the strength and security to share her statement. There are limits, then, to social media, and instead it was a sensitive, traditional journalist who empowered Duffy. This kind of journalism can actually improve the mental health of pop stars and other cultural figures – more than ever in the wake of the death of tabloid-hounded TV presenter Caroline Flack.

What will happen next? The moving certainty of Duffy’s reckoning with her past – “in the last decade, the thousands and thousands of days I committed to wanting to feel the sunshine in my heart again, the sun does now shine” – is its own conclusion, and a reckoning that will likely be deepened by a dialogue with a journalist she trusts. But there are cautionary tales from other female pop stars in the #MeToo moment, who have had their narratives spun out by the centrifugal misogyny on social media. Swift won a civil court case against a man who had groped her, but goodwill was limited by the antagonism towards her from spats with stars such as Nicki Minaj and Kanye West, and over her supposed lack of political awareness. Kesha had a bruising legal battle with producer Dr Luke, that dragged down a determinedly hedonistic comeback album into an abuse narrative. Then there’s Lily Allen, who said her career was damaged by having to avoid a record executive she claimed sexually abused her. But Allen and other female pop stars are also more subtly wounded: pop music is escapist, and perhaps a deep-rooted form of misogyny is that our culture just doesn’t like these women complicating heartbreak songs with more profound horrors. None of them have had quite the same chart success they once did, and it’s possible that these unpleasant, knotty stories are a factor.

Duffy, who has been away from the limelight for so long, is not freighted with the same multivalent fame as Swift, and will hopefully be the beneficiary of mostly sympathy from a public glad to see her again. But she re-enters a culture that is so different to the one she left: one where we all now have the microphone, and can shout anything into it. She has moved on, but will we let her?

Yahoo News

Yahoo News