As the Eagles celebrate their Super Bowl victory, Mark Brunell's story is a reminder of the sport's darker side

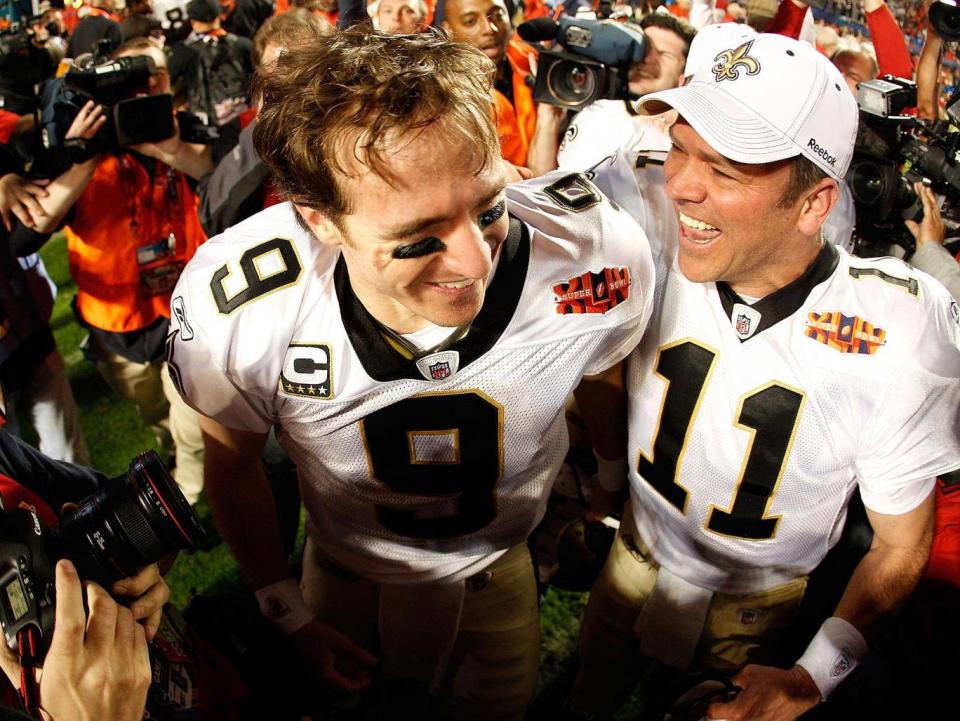

It was a swell party. It could not be otherwise. Five years after the city was all but destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, five years after the Louisiana Superdome had been taken over by 16,000 homeless and hopeless refugees, the team that played there, the New Orleans Saints, had won the greatest prize in American sport. They had won the Super Bowl for the first time in their history.

Mark Brunell was nearly 40 when he went on to the pitch and saw his wife, Stacy, and his father, David. All three burst into tears. “I am sure I cried a few times when I was 11 years old but this was the first time I had broken down as a professional,” said the quarter-back. “When you join the NFL the ultimate goal is to win a championship and it had taken me 17 years to get to that place. The feeling is astonishing.” Later that night, the Saints coach, Sean Payton, took the trophy to his room at the Miami Intercontinental put it on a table, knelt down, and said a prayer.

Everyone who was involved in the Philadelphia Eagles’ Super Bowl triumph in Minneapolis on Sunday would recognise those stories from eight years ago. The betting is that quite a few will recognise the story that follows.

For all the money that floods through the Super Bowl – $7.5m for a 30-second commercial, the $1billion television contracts – the average NFL player is paid less than his equivalent in basketball, baseball and ice-hockey. The average career lasts six seasons and many NFL players face financial ruin once the party is over.

The magazine Sports Illustrated estimated that three quarters of retired players would at some time face financial difficulty. A study by Washington University concluded that 16 per cent would file for bankruptcy.

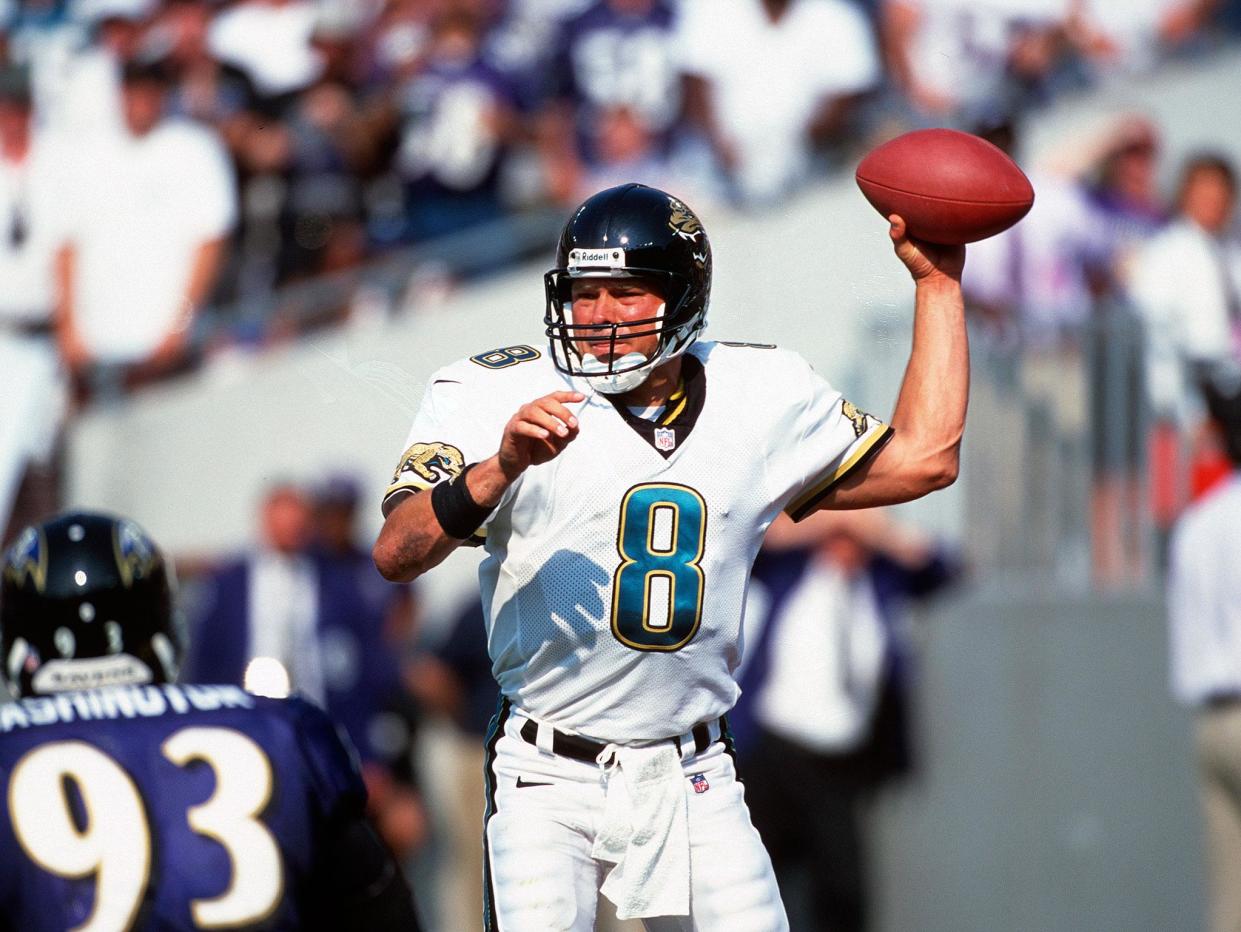

Mark Brunell was one of them. It is estimated he was paid $52m in a career that spanned the Green Bay Packers and the Washington Redskins as well as the glittering years in Jacksonville.

He did not gamble it away, although it might have been better if he had. Then, he would have owed nothing. Instead, by investing in property and guaranteeing business loans Brunell found himself owing $24m when the market collapsed. Swept away with it was the family home – a $9m beachfront house at Ponte Vedra.

He survived and when we meet he is carrying out a coaching session in London teaching Jag-Tag, a simplified form of the game that doesn’t require helmets, in the shadow of Tower Bridge.

The Jacksonville Jaguars, where Brunell set numerous records during his eight years at the club, are the NFL’s biggest investors in the British market and their ‘Gridiron Grant’ will pay the university fees of two British students who are involved in American football in their community or who play Jag-Tag. Brunell commentates, is a high-school head coach in Jacksonville and is big on education, particularly financial education.

“When you are done playing there is a transition period,” he said. “You go from a very structured life, where everything is scheduled for you. You are surrounded by your team-mates, you get to play on Sundays, you are famous, you make a lot of money. Then all that comes to a screeching halt and your first thoughts are: ‘now what do I do?’”

“For a lot of guys it is very, very difficult to go from being the centre of attention, to being the star to not having that. Being famous had its benefits, particularly in a small market like Jacksonville, but then you have to make your own way. Most professional athletes do not have a finance background, many of them don’t know how to manage money. Professional athletes, by their very nature, tend to be trusting people.

“From a very early age they take orders from their coaches. They are told when to train, when to go to the hotel, when to assemble for a team meeting. They don’t tend to question a lot of things and they are also big targets.

“The salaries are public knowledge, people want to take advantage and when they are given bad advice, you don’t tend to question it because athletes will always assume the person advising them has their best interests at heart because when you’re a footballer that’s what you always assume.”

It surprises Brunell that he is a high-school football coach; but the emphasis is on fun rather than seeing his charges at Jacksonville Episcopal forge a professional career. His 16-year-old son is one of his team and he cares little whether he follows him into the NFL or gains a football scholarship.

“There should not be that pressure to succeed at a young age,” he said. “The whole point of playing any sport, is that it should be fun. I played for 19 seasons and I will tell you something that will surprise you; when you play the Super Bowl it feels like any other game of football. Before and after, the feelings are very different but during the game, no.”

Jacksonville Jaguars in partnership with LGT Vestra US have launched Gridiron Grant, the UKs first American football scholarship. For more information please visit www.gridirongrant.co.uk

Yahoo News

Yahoo News