Eddie Van Halen was the heir to Hendrix, fusing technique with glorious pop

Think of Eddie Van Halen as a time traveller as much as a guitarist, someone who saw the future and fetched it back into the present. “What Eddie Van Halen did was reinvent the electric guitar,” says Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott. “He took it to the next level. He did what Hendrix did in 1967. He made people start listening again.”

He was far ahead of the times, in fact, that his playing could be used to symbolise something unearthly: it is him playing on the cassette that Marty McFly uses to convince his future father he is an alien in Back to the Future – a burst of Van Halen’s squalling, squealing playing, then the words, “silence, earthling!” In 1985, that was a joke all the watching audience understood. Those other players? Yeah, they shred. But Eddie? He’s one step past that.

That much was evident on the debut album by his band, also called Van Halen, released early in 1978. The songs themselves were revolutionary – hard rock, but with a pop edge; a new, sunny, Californian sound that owed little to the bands who had dominated guitar music earlier in the decade – but it was the second track on the album that proclaimed Eddie Van Halen as the heir to Hendrix.

During recording, he had been noodling in the studio, fiddling around on a solo he would play club shows. Producer Ted Templeman overheard, and realised this needed to be showcased. And so the second track on the album, Eruption, was simply 102 seconds of Eddie Van Halen bombing up and down the neck of his guitar at light speed, bringing in classical scales, and playing something that had never been heard before in a tone – which became known as the “brown sound”. That an instrumental could be the second track on a rock debut album was unusual enough; that it could be the most important track on the album was extraordinary. That 102 seconds could reshape heavy rock guitar completely was unprecedented.

An older generation knew what he had done. When Van Halen opened for Ted Nugent in 1978, Eddie told Esquire, Nugent was convinced the younger man’s playing had to be some sort of trickery. “He starts playing my guitar and it sounds like Ted,” Eddie told Esquire in 2012. “He yells,’You just removed your little black box, didn’t you? Where is it? What did you do?’ I go, ‘I didn’t do anything!’ So I play, and it sounds like me. He says, ‘Here, play my guitar!’ I play his big old guitar and it sounds just like me. He’s going, ‘You little shit!’ What I’m trying to say is I am the best at doing me. Nobody else can do me better than me.”

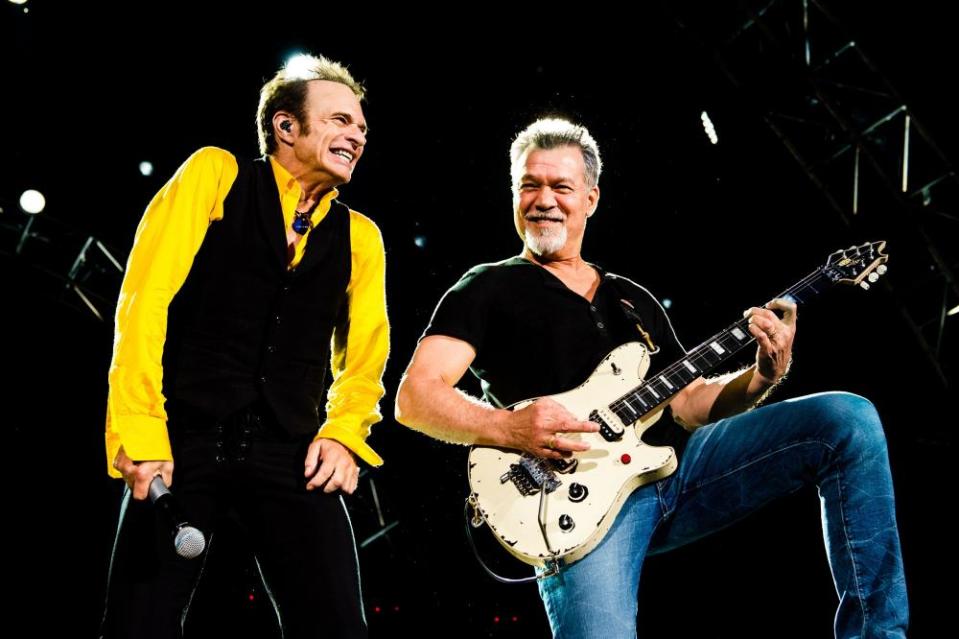

As David Lee Roth, Van Halen’s singer, told me: “When Edward plays you might never have heard the material before and you instantly recognise it as fast as, say, Jimi’s guitar.”

Nobody else can do me better than me

Eddie Van Halen

What set Eddie Van Halen apart from the shredders who followed – Yngwie Malmsteen, Joe Satriani and the like – was that he didn’t just play; he could write songs. Huge, glorious, memorable songs. Though he always saw himself as a hard rock player, he also knew how to write pop, and so Van Halen were never just a band for the guitar nerds. Though Van Halen albums always had some showcase for Eddie’s playing – Spanish Fly, Tora! Tora!, the opening of Mean Street, Cathedral – they were usually brief, and his soloing within songs was surprisingly to the point (across the first six VH albums, the ones with David Lee Roth, only three songs last longer than five minutes; this was not a self-indulgent band). His skills were just as often displayed in little flourishes – a guitar equivalent of a drum fill – fitted into the spaces in riffs, or between Roth’s lines. If you can make an impact in a few seconds, why bother wasting more time?

That he thought of the song first and the possibilities for his ego second were evident from the band’s only US No 1, Jump. Eddie had written the synth riff years before, but his bandmates rejected it. “Dave said that I was a guitar hero and I shouldn’t be playing keyboards. My response was if I want to play a tuba or a Bavarian cheese whistle, I will do it.”

Jump was the lead single from 1984, an album that slightly divides Van Halen fans – there are those who feel it a bit slight – but it’s an album of breathtaking imagination, where Eddie’s playing and the songs themselves merge into a seamless whole. Take Top Jimmy, in which Eddie appears to be playing lead and rhythm all at the same time, creating something fabulously intricate, yet with a lightness of touch that it makes it feel like a soufflé rather than stodge.

You can hear the strength of Eddie’s songs on an album that came out last year, when the Bird and the Bee – superproducer Greg Kurstin and singer Inara George – released an album of Van Halen songs. They changed the instrumentation, not the structure of the songs, which made plain quite how good they were, and just how adaptable they could be. Unless you are wholly wedded to the idea of Van Halen as a hard rock band, it’s highly recommended.

So it’s almost natural that the solo Eddie is most famous for isn’t even on a rock song, let alone a Van Halen song. It’s a 20-second section, reeled off in half an hour, for which he was unpaid. That was Michael Jackson’s Beat It, and the solo was credited with helping Jackson cross over from an R&B audience to being the world’s biggest pop star. It was uncredited, but word soon got out, and his bandmates duly blamed him for Thriller keeping 1984 from No 1 on the Billboard album chart.

Eddie Van Halen doesn’t necessarily sound as though he were an easy man – the band’s internal politics were clearly complex, to say the least; Roth’s replacement, Sammy Hagar, would later say the alcoholism that Eddie eventually got the better of turned him into a “vampire” – and he rarely gave interviews to humanise himself (and when he did, his exasperation with bandmates past and present often crept in). But the playing is what matters. And God knows, Eddie Van Halen could play.

The last word, as ever, should go to Roth, whose relationship with Eddie – and his drummer brother Alex Van Halen – was complex at best, open warfare at worst. Still, he knew an incredible thing when he heard it. “Who does endings better than Van Halen live?” he said. “I’ll send you a ticket. I’m ready to argue this. Unarguably the best endings ever, right? They sound like the end of everything. Biblical. And the guitar solo? It is a religious icon.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News