End wall of silence that helps gangs thrive, says top prosecutor

London's top murder prosecutor today appealed for an end to the “wall of silence” that is protecting gang killers from justice.

Julius Capon warned that a lack of co-operation within some communities was hindering efforts to put murderers behind bars. He said cases affected by the refusal of witnesses to provide evidence included shootings at venues where hundreds of people had been present.

Others included fatal stabbings in which friends of the victim — as well as those linked to the perpetrator —had refused to testify despite being at the scene. Mr Capon, who leads a 14-strong CPS team of homicide prosecutors, said they were striving to overcome the problem by using CCTV, phone tracking and other evidence to prove offenders’ guilt and had managed to increase the number of convictions and their success rate in recent months.

But he said even more guilty verdicts could be obtained with greater public support and it was time for those in communities affected by gang crime to “stand up and be counted” to stop killers staying free.

Mr Capon’s comments follow the publication of Met figures showing that only about one in 10 violent knife crimes in the capital between the start of 2016 and the end of June this year had so far led to a charge.

‘Everyone looked the other way’

The refusal of witnesses to testify allowed the killer of a 24-year-old student to go unpunished, a prosecutor said.

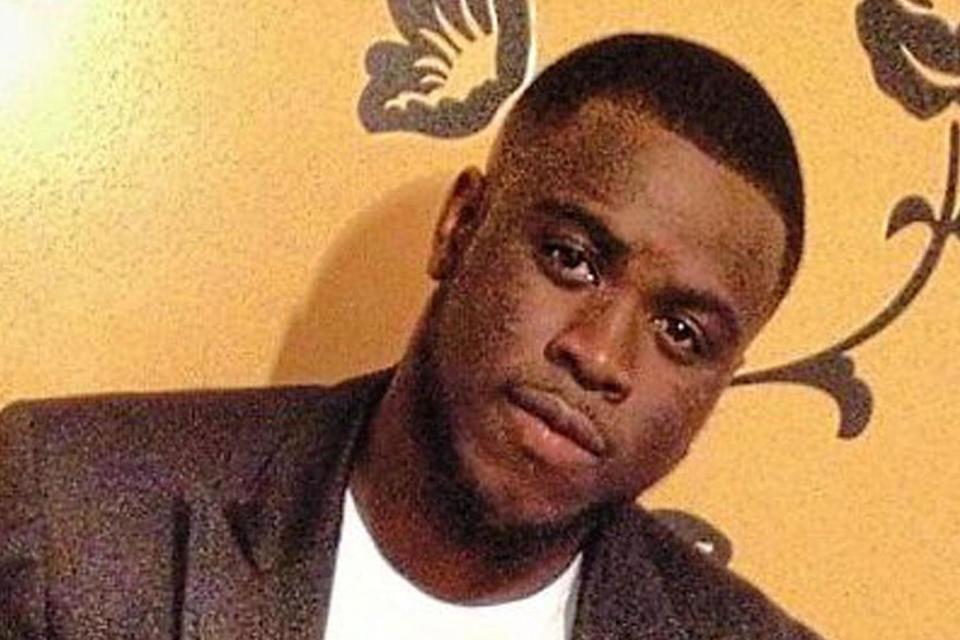

Victim Chleve Massi, pictured, whose distraught sister later killed herself by jumping off a ferry, was shot moments after walking into a party at the Sark Tower block in Thamesmead in February 2015.

Scion Fogah-Brown, 26, was jailed for eight years in January for possessing a firearm but was found not guilty of murder at the Old Bailey after claiming that someone else opened fire.

One of Julius Capon’s colleagues, lawyer Sarah Dale, who has dealt with 50 cases since joining the London homicide team, said: “Nobody saw it apparently. Everybody was looking the other way. We couldn’t get a single person to say who it was.”

In more than 2,500 of the unsolved offences, a key factor in the failure of the inquiry had been the refusal of the victim to testify against an attacker. Many further cases have similarly run into the sand because of the failure of other witnesses to give evidence.

Mr Capon said the lack of assistance was “a big problem” and added: “The wall of silence that we often get in gang cases is difficult to break a way through. We’ve had shootings in crowded nightclubs but hundreds of people there say they haven’t seen anything.

“Particularly in gang crime, you often find that the victim’s group don’t want to give evidence, just as much as the defendants don’t want to give an account. The message is if you as a community are worried about what is happening, someone needs to stand up and be counted for us to be able to bring people to justice.”

Mr Capon said that prosecutors and police used CCTV footage, mobile phone “cell site” tracking, automatic number plate recognition cameras, social media posts and other evidence to bring charges. They also sometimes use a “reluctant witness” procedure to compel them to testify, although this could fail if the person chose to lie.

But he added: “We’d rather have an eye-witness who says ‘he did it’ but we don’t often get that in murder cases. We also have to bear in mind that in a lot of those gang cases people were wearing scarves or masks so identification is always going to be difficult at the point of the murder.”

To help witnesses give evidence, prosecutors can apply to the courts for “special measures” which allow people to testify anonymously. They can also be taken to and from court by police and given further protection to ensure they are kept safe and their identities remain secret. The homicide team also meets every bereaved family to explain any charging decisions and what will happen in court.

The conviction rate for homicide cases in London fluctuates monthly and fell as low as 54.3 per cent in May. But it has risen since to above 80 per cent. Mr Capon said that another reason why convictions were sometimes not possible was that knife homicide victims in gang cases had often been carrying a knife themselves. This allowed the perpetrator to plead self-defence and either escape charges or potentially be cleared by a jury.

He added: “There are cases where we have been unable to rebut self-defence. That can be quite difficult to have to explain to a bereaved family.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News