Erdoğan has Turkey in his palm as key elections loom

All along Istanbul’s boulevards, the face of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan looms large. For 16 years he has ruled over his country, victorious in election after election, vowing every time that Turkey is on the path to reclaiming its status as a great power in the Middle East and beyond.

Turkey’s largest city is home to a variety of grandiose projects that channel this vision. In October, the government is scheduled to complete work on Istanbul’s third airport, which will serve 90 million passengers a year. A project to bypass the Bosphorus with new 28-mile (45km) waterway linking the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea – a project first proposed in the 16th century – will cost billions of dollars.

Turkey is less than a week away from arguably its most important elections in modern history. The victor in the presidential race will assume an office with extraordinary powers, which were narrowly approved in a referendum last year, and rule until 2023 – the centennial of the republic’s founding from the ashes of the Ottoman empire.

Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development (AK) party faces the prospect of losing its majority in parliament, but the 64-year-old, who has sought to position himself as a leader of the Muslim world as well as his country, is predicted to retain the presidency. He remains Turkey’s most popular and powerful politician despite an unexpectedly dynamic opposition.

“He’s a really great leader,” said Rumeysa Kadak, an AK parliamentary candidate likely to become the country’s youngest MP. “We can see that there is great pain in the world, and he is the leader to say the world is bigger than five [the permanent UN security council members], to say ‘stop’ to the world, and he’s the first person to say that.”

Independent polls suggest an easy victory in the first round, though without an outright majority, before more narrowly defeating a second-round challenger.

Muharrem İnce, a physics teacher and the main secularist opposition candidate, is most likely to make it into the final round with Erdoğan. His lively campaign has drawn thousands of people to rallies across the country. He has vowed to overturn restrictions on fundamental freedoms and restore the rule of law in Turkey.

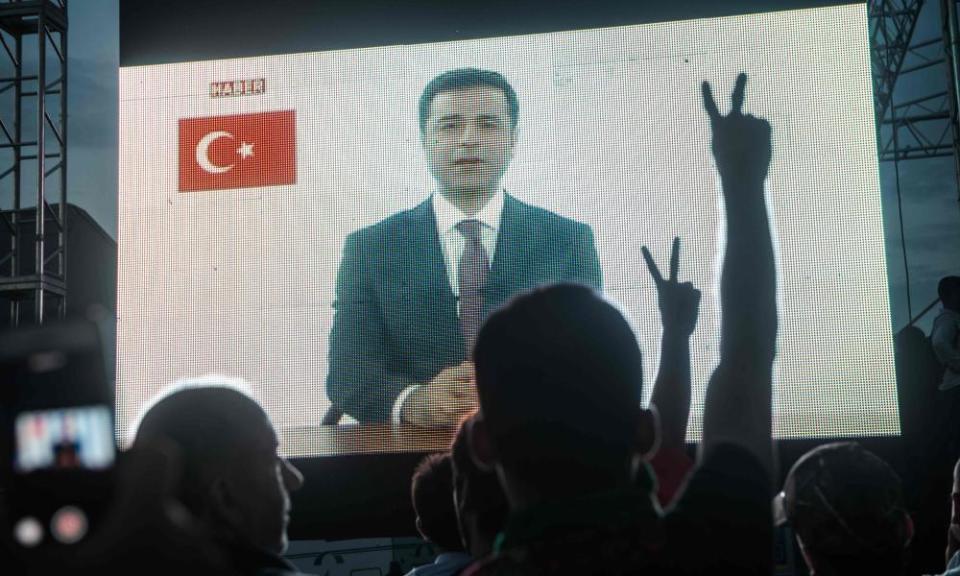

Meral Akşener, the leader of a breakaway nationalist party, has energised young voters in her attempt to outflank Erdoğan from the right, while Selahattin Demirtaş, the charismatic Kurdish leader, is running a presidential campaign from his prison in Edirne. On Monday, he gave a groundbreaking televised speech from the jail calling on voters to reject one-person rule.

However Erdoğan, often classed by human rights campaigners as a strongman leader alongside Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán, is likely to be re-elected. “Great Turkey wants a powerful leader,” say his election posters.

“There are two Turkeys I believe: one imagined Turkey, by western writers, and one real Turkey, here, and we are witnessing that Turkey,” said Fahrettin Altun, an expert at the Foundation for Economic, Political and Social Research, a thinktank with ties to the government. “Voters believe that a powerful Turkey can be obtained by Erdoğan’s leadership [and] they believe that Erdoğan is a symbol of mainstream Turkey. Erdoğan is the voice of Turkish society.”

That last claim is arguable. In the last major vote – the referendum on presidential powers – Erdoğan won by a razor-thin margin amid allegations of fraud.

Altun said, however, that opposition leaders’ attempts to imitate Erdoğan proved he offered a good representation of Turkish society.

İnce has a populist veneer to his speeches and occasionally adopts crowd-pleasing, anti-western slogans, such as vowing to close the İncirlik airbase used by the US if Washington fails to extradite Fethullah Gülen, a Pennsylvania-based preacher accused of masterminding the 2016 coup attempt. Mimicking the president’s religious piety, both Akşener and İnce have emphasised that they are personally devout.

Erdoğan and the AK party’s promise to its voters has often rested on two pillars: economic growth and democratisation, which in effect has meant a greater voice for their once-beleaguered base. Supporters of the president admire his public piety, largely because it has allowed those who identify as devout Muslims to be part of mainstream society after decades of vilification by their secular countrymen and women.

Under Erdoğan’s leadership, headscarves are allowed in parliament, universities and public buildings, a transformation that few of his supporters are likely to forget. “As a teenager in Ankara in the 1980s we couldn’t wear the headscarf at school,” said Ravza Kavakçi, an AK party MP. “So on the weekends or outside of school, if people didn’t insult me I would feel like I was invisible, I would worry that they could not see me.

“But with the democratisation I was accepted as a human being. As a Muslim it didn’t matter what others said or did, I was accepted the way I was.”

The economy, in the meantime, has suffered a few shocks. Youth unemployment remains high, and the value of the Turkish lira has plummeted against the dollar. But the strong leader image has left most voters convinced that only Erdoğan can fix what ails Turkey.

Kiraz, a 55-year-old AK party voter, said she had little patience for opposition leaders claiming to be religious or wanting to save the country. She was sitting with friends in the courtyard of the Fatih mosque in Istanbul, named in honor of Mehmet the Conqueror, who wrested control of Constantinople from the Byzantines.

She called the opposition presidential candidate İnce “a liar who will ruin everything”.

“There are no lines in the hospitals, we have roads, parks, everything, what more do we want?” she asked.

Zeynep Varol contributed to this report

Yahoo News

Yahoo News