Erik Hauri: scientist who discovered water on the moon

When early astronomers gazed up at the moon, they mistook its dark patches for seas. By the time astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Sea of Tranquility in 1969, scientists knew it was nothing but terra firma.

Most researchers concluded that the moon was bone dry, a celestial desert. But in a set of papers published beginning in 2008, American geochemist Erik Hauri helped demonstrate that water existed on the moon after all – and that the moon’s interior might contain as much water as the Mediterranean sea.

Hauri, who died of cancer aged 52, helped usher in a new era in our understanding of the moon, an astronomical object now known to have ice on its poles and water deep inside its mantle.

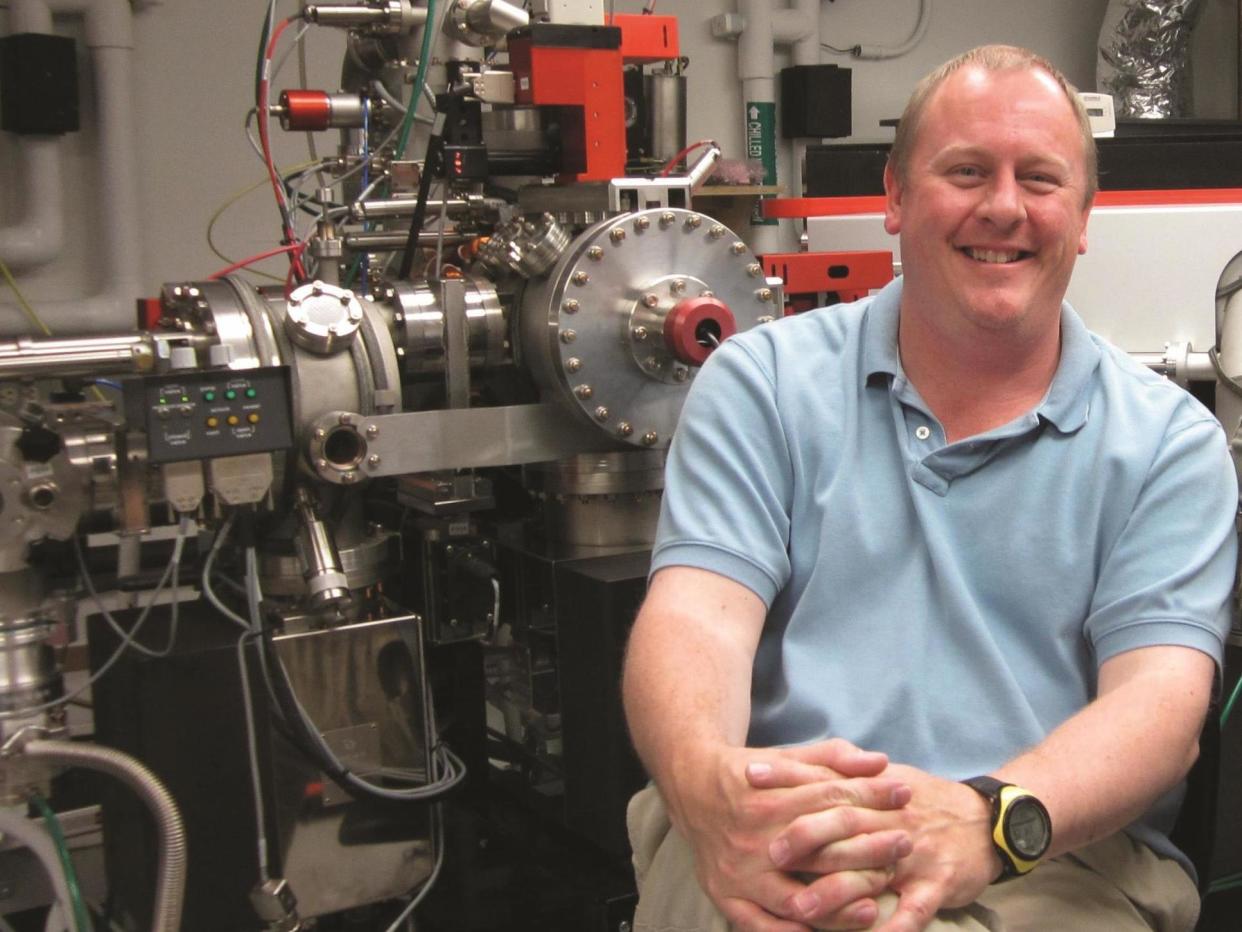

A longtime researcher at Washington’s Carnegie Institution for Science, Hauri, was first recognised for his work with highly sensitive instruments called ion microprobes, which he pushed “to their absolute technical limits,” says Larry Nittler, a cosmochemist and Carnegie colleague.

Using techniques he developed in the 1990s, Hauri used the instruments to examine slivers of shards, portions of rock the width of a human hair or smaller. He detected trace amounts of elements such as hydrogen and carbon, down to a few parts per million – work that enabled him to obtain key insights on the Earth and moon.

A onetime marine biology student, Hauri began studying rocks after deciding marine animals were fickle and uncooperative. But he spent much of his career outside the lab, collecting volcanic samples from Hawaii, Iceland, Alaska and Polynesia that shed light on the movement of elements and minerals deep inside the Earth.

He was focusing on water, which has a broad impact on volcanic eruptions and the movement of tectonic plates, when his friend Alberto Saal suggested they conduct measurements for hydrogen, water and other volatile substances using the lunar samples of the Apollo programme.

“When people measured these moon rocks they never found anything,” says Saal, a Brown University geochemist who attended graduate school with Hauri at MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “We had a good technique. Nothing had been done on hydrogen for a long time. We said, ‘Why not try?’”

It took three years for the researchers to obtain their samples from Nasa, which twice rejected their research proposal, Saal said. But when he and Hauri reviewed their findings, “It was like a bomb had exploded in our hands.”

Their work centred on a thimble’s worth of orange-tinted soil, which included tiny beads of volcanic glass collected by astronaut and geologist Harrison Schmitt in 1972. Described by Hauri as geological “time capsules”, the beads were formed when the moon was relatively young, when lava was ejected from volcanoes and cooled so fast that it turned to glass before falling to the ground.

In a 2008 article in the scientific journal Nature, the scientists reported that some of the beads contained trace amounts of water – about 50 parts per million. Three years later, in an article in Science, Hauri and his colleagues reported finding far more – about 100 times more water than had previously been believed. Their research indicated that the mantle of the moon, a hot, dense region just below the surface, contained about as much water as the upper mantle of the Earth.

“If you take our measurements and use them to estimate the water content of the interior of the moon, you arrive at a volume of water that’s equivalent to the Mediterranean Sea. Now that’s a fair bit of water,” Hauri told NPR in 2011.

Their findings also raised new questions about the origin and evolution of the moon. Scientists have long believed that the moon was formed through a massive collision some 4.5 billion years ago, when a Mars-sized object struck Earth, knocking off a chunk of material that coalesced to form our lunar neighbour. Under that theory, however, the heat of the collision was assumed to have vaporised any water.

“Our models for formation of the terrestrial planets involve these types of large collisions, which led to a prevailing wisdom that all the terrestrial planets formed bone-dry,” says Richard Carlson, director of Carnegie’s terrestrial magnetism department. “A number of observations, particularly Erik’s detection of water on the Moon,” have forced scientists “to consider more complicated, but likely more accurate, models.”

Erik Harold Hauri was born in Waukegan, Illinois, 40 miles north of Chicago, in the mid-Sixties. He grew up in Richmond, Virginia, a small town near the Wisconsin border, where his mother was a homemaker and his father was an auto mechanic and avid fisherman, taking Erik on trips that spawned a lifelong interest in the outdoors.

Neither parent opted for further education. But Hauri graduated in geology and marine science at the University of Miami in 1988. While interviewing for the doctoral programme at MIT, his future adviser, Stanley Hart, told him that he might be leaving the school in two years.

Then at MIT, he received his doctorate in four years, in 1992, and joined Carnegie in 1994.

Hauri received early-career honours including the Houtermans Award from the European Association of Geochemistry and the Macelwane Medal from the American Geophysical Union. He was elected a fellow of both organisations.

Outside of the lab, he played guitar – worship music at church, and progressive metal at home. He also became a self-taught luthier, making more than a dozen guitars and bass guitars by hand after finding himself unable to acquire a 12-string Fender Stratocaster in a store.

In addition to his wife of 31 years, Tracy (nee Spears), survivors include three children, his father, a sister and a brother.

Hauri and Saal continued their lunar work in recent years, finding that water on the moon and on Earth appeared to originate from the same source, a class of meteorites known as carbonaceous chondrites.

Others took up the hunt for lunar water as well, which picked up steam after Nasa announced in 2009 that they had found the equivalent of 26 gallons of water after a satellite was intentionally crashed at the moon’s south pole.

In 2017, a pair of researchers at Brown published a study suggesting that water was spread across the moon’s mantle, rather than isolated in certain water-rich regions. And in August, a new study found “direct and definitive evidence” for water ice on the surface of the moon’s poles. It might someday be possible, scientists noted, for that ice to be used as a resource for a station or colony on the moon.

Erik Hauri, scientist, born 25 April 1966, died 5 September 2018

© Washington Post

Yahoo News

Yahoo News