What the EU's coronavirus rescue fund deal means for Brexit

Angela Merkel keeps her cards close to her chest but, when the German Chancellor lays them on the table, all of the EU’s leaders sit up and take notice.

Her interventions, when they do arrive, are significant and with one eye firmly on the future of the European Project.

That was true in securing the EU’s massive economic stimulus plan to respond to the devastating impact of coronavirus and it will be true as Brexit trade negotiations near their endgame this year.

On the fifth day of tense summit talks EU heads of state and government agreed in the early hours of Tuesday morning to an unprecedented €750billion coronavirus rescue fund and a trillion-euro budget for the next seven years

Without Mrs Merkel the deal would never have happened, and many EU citizens in the hardest-hit countries - such as Spain and Italy - would be asking themselves what use the Union is.

The European Commission will now borrow against the EU Budget to raise capital for the rescue fund, avoiding the need for the poorer and hardest-hit member states to take more expensive debt on their public budgets.

This busts the long-standing taboo over raising large amounts of common debt and is a major step forward for EU integration.

Fiscally conservative northern member states, led by the Netherlands, were reluctant to underwrite spending in other countries.

Conscious of opposition in her CDU party to funding another euro bailout, Mrs Merkel originally aligned herself with the “frugal” countries.

After her effective response to coronavirus in Germany saw her flailing popularity surge back, Mrs Merkel took the political risk of swapping sides and restarted the EU’S stalled Franco-German policy “engine”.

She joined Emmanuel Macron at the head of a group of poorer southern EU countries including Spain and Italy demanding a rescue fund made up of handouts, which do not need to be repaid, and loans.

Mrs Merkel, who is serving her final term, secured for her legacy a further deepening of ties in the bloc in the face of a crisis that the French president warned could destroy it.

It is not the first time Mrs Merkel, who is nicknamed Queen Europe by admiring officials in Brussels, has risked her career for the EU.

Her decision at the height of the Migration Crisis in 2015 to throw open Germany’s borders to the one million Syrian refugees crossing the Continent proved very unpopular.

Her CDU party posting their worst results of the post-war era at 2017 elections that handed her her fourth term.

Mrs Merkel is pragmatic and willing to take risks. Germany now holds the six-month rotating Presidency of the EU, making Berlin an even more influential player in Brussels as the Brexit transition period comes to an end on December 31.

Her habit of intervening in key moments in EU history led many Brexiteers to confidently predict she would go over the heads of the European Commission’s Brexit negotiators and order a deal done.

But Germany is a reluctant leader of the EU. Its wartime history and the desire to expiate that national guilt means Mrs Merkel will put the EU’s, and not the German car industry’s interests, first.

In 2016, she refused to grant David Cameron’s wish for restrictions on EU freedom of movement rules in his ill-fated attempt to secure reforms from Brussels ahead of the Brexit referendum.

The Chancellor, who was born in communist East Germany, put her foot down as a matter of principle, despite the risk of Britain voting to quit the EU.

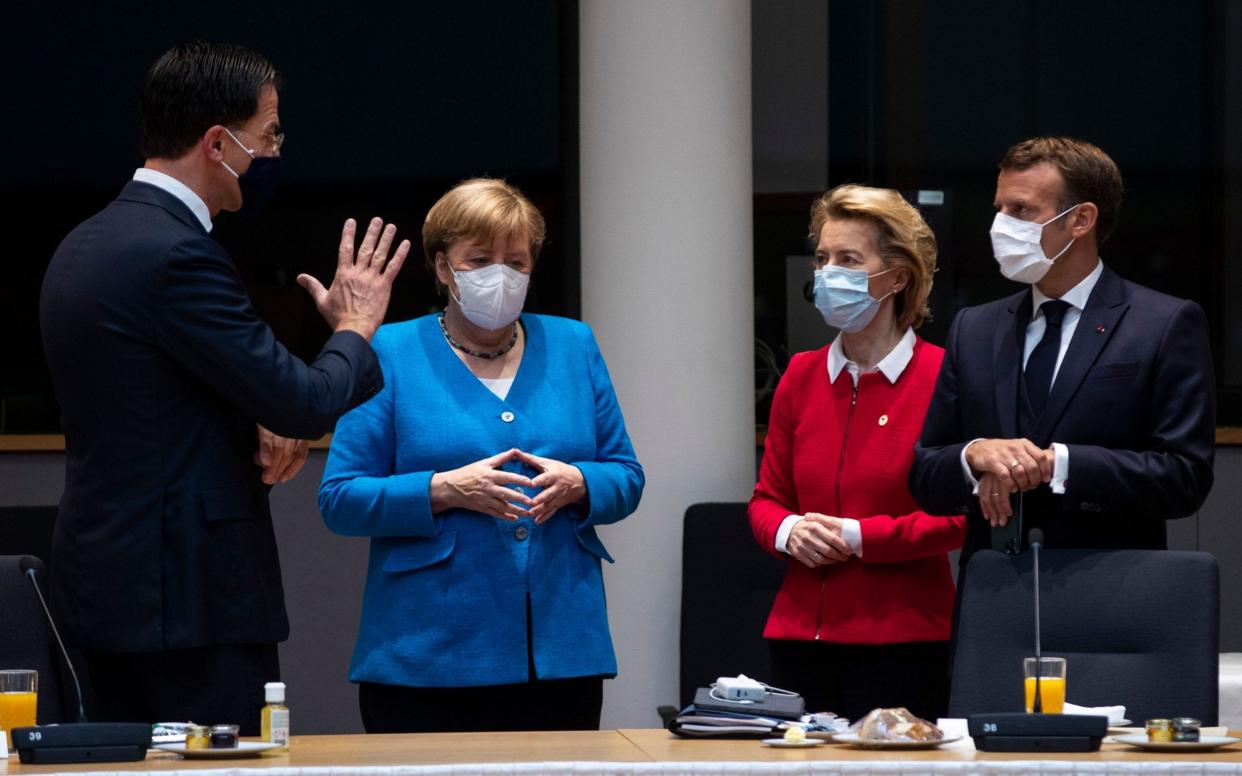

As tempers frayed during the coronavirus summit, Mr Macron accused Mark Rutte, the prime minister of the Netherlands of acting like Mr Cameron and taking on the role of an intransigent UK in the European Council.

The EU has set an end of October deadline for the deadlocked free trade agreement with the UK to be finalised so that there is time to ratify the deal before the end of the year and transition period. Failure will mean both sides trading on less lucrative WTO terms and with tariffs from January 1.

Mrs Merkel has a horror of a no-trade-deal Brexit but will not support an agreement which threatens the EU’s rules and by extension its future. She has told the EU to prepare for the worst.

After the marathon coronavirus summit, Mrs Merkel’s full attention can now turn to Brexit, another historic challenge for the EU.

But, this time, her answer to the crisis cannot be “more Europe”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News