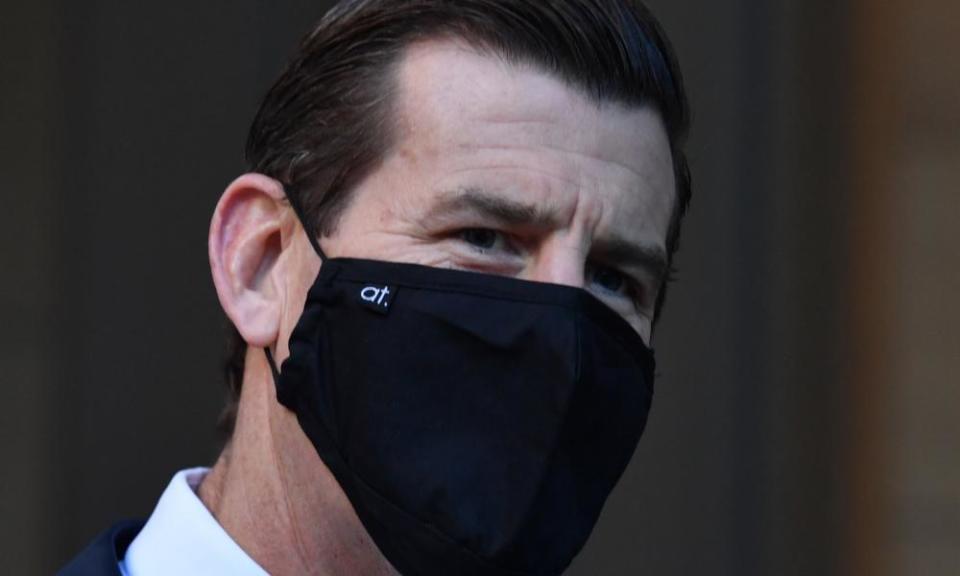

‘Even if I die I will tell the truth’: witness speaks out at Ben Roberts-Smith defamation trial

After two full days giving evidence Mohammed Hanifa Fatih was formally excused.

But he wasn’t yet finished.

Staring down a computer screen into an arcane courtroom on the other side of the world; having answered, since dawn, dozens of questions about a violent raid on his village nine years ago; he had one more thing he wanted to say.

Hanifa had been interrogated for hours over whether his uncle, Ali Jan – killed during an Australian SAS raid on his home of Darwan in September 2012 – was a member of the Taliban or a sympathiser for the terrorist network.

“Look, brother, I am a witness, I am not afraid of anybody, even if I die I will tell the truth,” Hanifa said, standing, his voice rising.

“You know this is the Pashtun custom, it is the tradition and it is the law. If you witness something like a crime you have to testify about it, even if somebody wants me to go to Australia or to the US I will go there and testify, Ali Jan was a labourer, he was a labourer, he was a labourer.”

In the defamation trial brought by the former Australian SAS corporal Ben Roberts-Smith, two witnesses from Darwan told the court this week they had seen a “big soldier” kick Ali Jan, kneeling and in handcuffs, off a cliff into a dry creekbed.

They say they heard shots fired and later found Ali Jan’s body, disfigured by gunshot wounds to his jaw, skull and chest, in a cornfield.

Even by the standards of this extraordinary trial, this was a remarkable week.

The simple logistics of putting this evidence before Justice Anthony Besanko have, at times, seemed insurmountable.

Unable to travel to Australia, three Afghan witnesses and their families have been held in Kabul safehouses for weeks, waiting for the chance to give evidence. Previously they had been staying in Kandahar, which they had to leave because of the deteriorating security situation. Some have not been home for a year.

To appear in court this week they have had to rise before dawn and make their way to a legal office in central Kabul, to begin giving their testimony at 4.45am.

Pashtu speakers, they require an interpreter to answer the questions coming from half a world away: but without an interpreter in Australia with both the sufficient translating qualifications and security clearance to act as intermediary, their answers have bounced – on secure lines – from Kabul to an interpreter in Ontario, Canada, to courtroom 18D of Sydney’s federal court.

Several times a day, the power has gone out in Kabul, with the witnesses plunged into darkness for minutes until a generator kicks in and brings them back online.

Court documents state that giving evidence could attract retribution for the Afghan witnesses: at least one of them told the court he cannot get home because of increased Taliban violence across Afghanistan and the terrorist outfit’s tightening grip on the country.

A fourth witness who was set to be called could not get to Kabul from her village near Kandahar. Those roads are impassable now and to move is too dangerous.

Roberts-Smith, a recipient of the Victoria Cross, is suing three Australian newspapers for defamation over a series of reports he alleges are defamatory and portray him as committing war crimes, including murder, during his deployments in Afghanistan.

One of the key allegations made against him concerns the death in Darwan of Ali Jan. Two versions of events have been presented to the court.

The newspapers allege that Roberts-Smith murdered a handcuffed Ali Jan, by kicking him off a cliff into a dry river bed, then shooting him, or ordering a subordinate to shoot him. Ali Jan’s body was then allegedly dragged into a cornfield and a radio – evidence of Taliban connection – was allegedly planted on his corpse.

Roberts-Smith has consistently and vociferously denied this version of events.

In his evidence he told the court that he and a comrade had encountered Ali Jan as they were climbing an embankment to be “extracted” from Darwan by helicopter. Ali Jan had been carrying a radio, refused an order to stop and was lawfully “engaged”, Roberts-Smith said. He was a legitimate target shot dead in a firefight, in accordance with the laws of war.

Roberts-Smith has maintained he could not have killed Ali Jan as alleged because there was no cliff from which to kick him. “There was no cliff … there was no kick,” he told the court.

‘A big soldier who was wet up to here’

On 11 September 2012, Australian SAS soldiers descended by helicopter on Darwan, in Afghanistan’s southern Uruzgan province, searching for a rogue Afghan national army soldier called Hekmatullah, who had killed three Australian troops a fortnight before in a brutal “green-on-blue” insider attack. Roberts-Smith was among them.

Three Afghan witnesses who were in Darwan have told the court that Ali Jan was a farmer, visiting from a neighbouring village, when he was detained, handcuffed and hit by Australian troops, as they interrogated him seeking information on the Taliban.

Hanifa told the court, “a big soldier who was wet up to here” – gesturing to the bottom of his ribcage – “and with sand from the river on his uniform” had punched and kicked him repeatedly as he interrogated him, while handcuffed.

Earlier witnesses in this trial have described Roberts-Smith as “a tall, imposing, warrior-like figure”. The court has also heard, from Roberts-Smith himself, that earlier in the raid, he had swum alone across the nearby Helmand River to pursue and kill a suspected insurgent.

Hanifa said he had seen the big soldier with the wet, sandy uniform kick Ali Jan in the chest, causing the handcuffed man to fall down the steep embankment into a dry creek bed.

“He was rolling down, rolling down until he reached the river,” Hanifa told the court. Hanifa said he had lost sight of Ali Jan as he rolled down the embankment but had later heard gunshots being fired, and had seen Ali Jan’s body being dragged by two soldiers “to the berry trees” nearby.

Hanifa said once the Australian soldiers left, he had been untied by a woman in his village and he had discovered Ali Jan’s body.

The witness said the Australian soldiers had planted a radio on Ali Jan’s body – a practice known as “throwing down”.

“By God, he had nothing with him,” Hanifa said. “He had no equipment with him … They put those things with his body.

“These are lies.”

A second witness, Ali Jan’s brother-in-law Shahzad Aka, also told the court he had seen “the big soldier” kick Ali Jan.

“I saw the big soldier … Ali Jan was facing the soldier and then the soldier kick him and he went down.”

All three Darwan witnesses insisted Ali Jan had no connection to the Taliban, and each individually said the radio photographed next to his dead body had been planted on his corpse.

“He doesn’t [didn’t] know how to work a watch,” said a Darwan villager, Man Gul. “He cannot operate a wireless device.

“This wireless device and then the white bag were not there, only there were the clothes on his body.”

Shahzad Aka told the court: “He didn’t have a wireless device, the soldiers put it on his body.”

Under intense cross-examination, the three men were repeatedly challenged on their evidence.

Related: Ben Roberts-Smith defamation trial could be delayed until November

Roberts-Smith’s barrister, Bruce McClintock SC, questioned whether the men had been coached on their evidence, had colluded with others over what they would say, or whether they were being paid to give evidence or seeking compensation for Ali Jan’s death.

Each repeatedly, resolutely said no.

“Your evidence is not true, is it?” McClintock asked Hanifa at one stage.

“I’m explaining what I saw with my own eyes,” Hanifa replied. “Whether you call it a lie or a truth, I leave it to the respected judge.”

McClintock: “The evidence you’ve given about seeing the ‘big soldier’ wet is completely untrue, isn’t it?”

Hanifa: “Whether you call it a lie, that’s up to you. But I have seen this person with my own eyes.”

Another adjournment expected

Roberts-Smith’s defamation trial has been delayed more than a year by the coronavirus pandemic and now faces further postponement because of Sydney’s Covid-19 outbreak.

The judge has said the case’s national security sensitivities mean he is unwilling to move the trial to another city, or to allow other witnesses to give evidence by videolink.

The major impediment is bringing witnesses to Sydney – now under lockdown – to give their evidence in person. Most of those to be called are serving or former SAS soldiers based in Perth, who would be unable to return to Western Australia should they come to Sydney.

The case will return to court on Monday to consider its next adjournment: resumption is not likely until November.

Bringing the evidence from Afghan witnesses forward, Besanko told the court that, given the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, “There is a substantial risk that the evidence of the Afghan witnesses will become unavailable if it is not taken soon.”

Having waited nine years since the raid on Darwan, Mohammed Hanifa Fatih has now been heard.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News