In the eyes of Beijing, the Quad poses a more menacing threat than Aukus

The Quad is a “sinister gang” whose members are “four ward mates with four different diseases” who “will become cannon fodder” if they dare to take on China, warned Global Times, the mouthpiece of the Communist Party in Beijing.

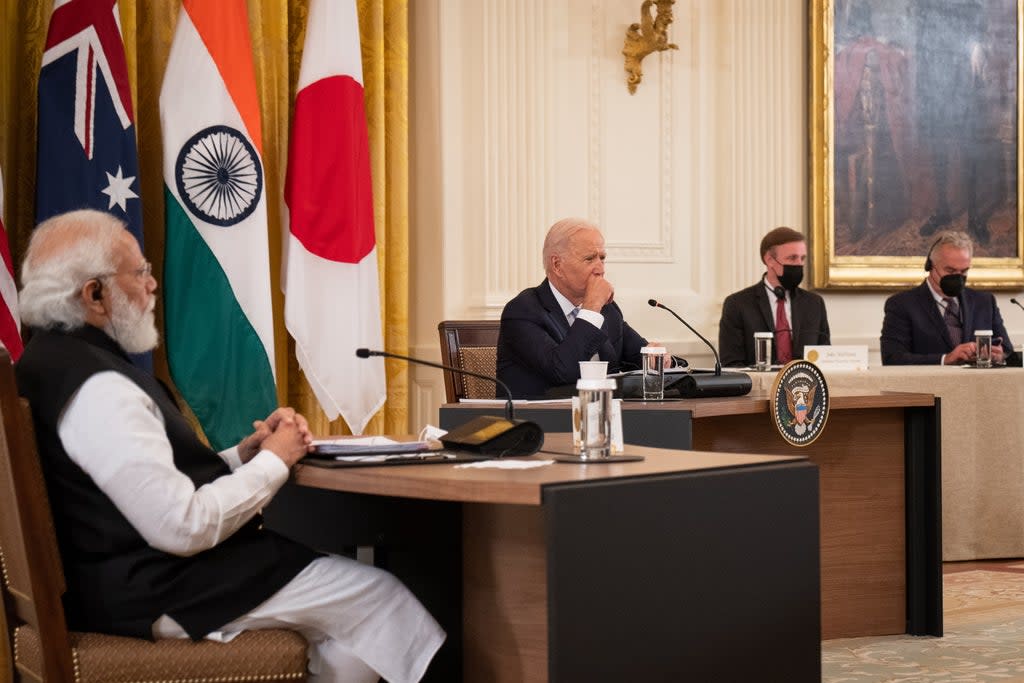

The ire expressed in the editorial was focused on the first in-person summit between the leaders of the so-called “gang”: the US, Japan, India and Australia, at the White House. The US president, Joe Biden, continued the newspaper, is putting “America first” even more than the former president, Donald Trump.

The last meeting of the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), held virtually in March, announced the delivery of a billion doses of Covid-19 vaccine to countries in Asia by the end of 2022. On this occasion, however, China and its aggressive policies is the main issue on the agenda. The group poses, strategically and militarily, more of a problem for Beijing than the much publicised Aukus agreement between Australia, UK and the US with its building of a nuclear submarine fleet for Australia.

All four member states have substantial armed presence in the Indo-Pacific, are augmenting it to counter Chinese expansion, and all feel that they face a threat from China, although the language used to described that threat is tempered in public pronouncements.

Two of the members have been in confrontation with China: India on the Himalayan border and Japan over disputed waters and Senkaku islands in the East China Sea.

Last month the navies of the Quad countries carried out the Malabar exercises off the coast of Guam. It originated as an annual bilateral naval drill between the US and India in the 1990s, then fell into abeyance but has now been reinvigorated on a larger scale to include Japan and then Australia. In April, these navies took part in the La Perouse exercise in the Bay of Bengal with France, in line with the Macron government’s decision to have a more prominent military presence in the Indo-Pacific. Despite the Aukus row between Australia and France over the cancellation of a submarine contract, more such exercises with French participation are expected to take place in the future.

The fact that this is the first face-to-face meeting since the Quad was set up 14 years ago is a sign of the group seeking to play a much more effective role. And that has come about directly as a result of China’s uncompromising approach on issues ranging from ownership of mineral-rich waters, crackdowns in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, threats to invade Taiwan and the coronavirus pandemic.

India had, until recently, been lukewarm about the Quad, but the clashes on its northern border with China appear to have concentrated minds in Narendra Modi’s government – it is now an enthusiastic member.

Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s prime minister, spoke on his way to Washington of Beijing’s growing “military influence and unilateral changing of status quo” which present a risk to Japan. Incursions by Chinese vessels near the Senkaku Islands took place on a record 157 days in a row earlier this year – part of a steady rise in such incidents. Defence minister Nobuo Kishi added that China’s actions have led to “strong concerns in regards to the safety and security of not only our own country and the region but for the global community”.

Australia, which faced punitive Chinese tariffs on exports and cyberattacks after calling for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid, joined the Malabar exercises last year. It is now also part of Aukus, despite the fact that China remains its main trading partner and further sanctions by Beijing will undoubtedly hurt the economy.

The talks between Mr Biden, Mr Modi, Mr Suga and Australian prime minister Scott Morrison are expected to be followed by an announcement on Covid and action on the climate crisis. They are also due to discuss cybersecurity and supply chains for semi-conductors and co-operation in developing 5G technology. Beijing has been accused of widespread use of cyberattacks and it currently effectively controls the semi-conductor market. The presence of Chinese companies in the telecoms infrastructure including, until recently, Huawei in the UK, has raised security concerns.

China had, in the past, sought to dismiss the Quad as being of no consequence. Three years ago Wang Yi, foreign minister and state councillor, said the group was “seafoam in the Pacific or the Indian Ocean; it may get some attention, but soon will dissipate”. But by last year he was warning that it was a “security threat” and the “new Nato” in the region.

Asked about the White House summit, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said: “It should not target any third party or harm their interest ... to form exclusive cliques targeting other countries won’t be popular and has no future.

“Relevant countries should abandon outdated zero-sum game thinking and narrow geopolitical concepts, take a correct view of China’s development, respect the hearts of the people in the region, and do more things that are conducive to promoting unity and cooperation of regional countries.”

But David Shullman, a China analyst with the Atlantic Council, held that Beijing should “really get the lion’s share of credit” for rejuvenating the Quad. Its aggressions against India, Japan and Australia, suppression in Hong Kong and threats against Taiwan “have given leaders in the region a new sense of urgency and common purpose”.

Robert Emerson, a British security analyst, added: “A lot of what is happening is made in China. The combative way the Chinese have driven through their policies was going to have consequences, and that is what’s happening now. They shouldn’t be surprised by this.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News