Facebook's getting better at identifying photos, and it wants your help

The world's largest social network is getting better at learning about your photographs, but it still needs humans to help it improve.

Facebook announced Thursday that it will make its computer vision research available to anyone who wants it, ideally creating a brainstorm that advances the technology that can automatically identify images.

SEE ALSO: Facebook really is keeping tabs on your political views

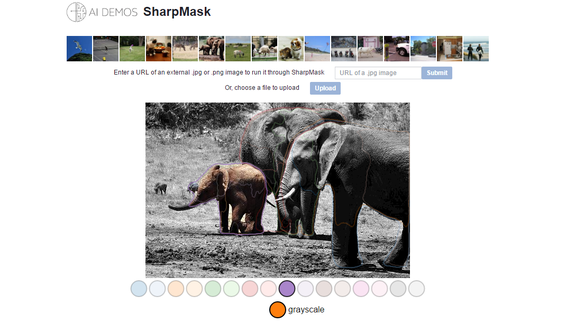

"We're making the code for DeepMask+SharpMask as well as MultiPathNet — along with our research papers and demos related to them — open and accessible to all, with the hope that they'll help rapidly advance the field of machine vision," Facebook research scientist Piotr Dollar wrote in a blog post.

If you're scratching your head, think of it this way: You probably deal with this technology on a regular basis if you're a Facebook user, even if you don't realize it. When you upload a picture and try to tag someone, Facebook will automatically suggest that person's name unless they've disabled the "tag suggestions" feature. The social network comes to recognize people based on their unique facial features once they've been tagged in enough photos, making future tags practically automatic. Users just have to approve Facebook's suggestions.

But computer vision is used for more than identifying your friends. Earlier this year, Facebook launched a new feature for blind users that employs similar technology to describe photographs in simple terms: "Two people, smiling, sunglasses, sky, outdoor, water," for example.

One day, image-recognition could make searching through your memories a snap. (Google Photos offers an instance of this in which you can type terms like "pictures of me smiling" and get results.) Facebook says there's also business potential here: Eventually, you could snap a picture of furniture to see where you can buy it, or take a photo of lunch options to see which has the most protein based on how the tech identifies each option. Perhaps it could learn melanoma patterns and tell you when to see a dermatologist. Eventually, the technology could be applied to video.

Reaching a new milestone

The photo recognition efforts are based on a form of artificial intelligence called "deep learning." In the most basic sense, deep learning is about interpreting tons of data through a series of "neural networks." While any person could point to a picture of an elephant and declare, "Yep, that's an elephant," the task isn't so simple for computers, which have to answer the basic question: What is the essence of elephantness? Is it anything with a trunk? Big ears? Four fleshy hooves hanging from a body? What if the creature is rolling around in mud, obscuring itself? And so on.

With its deep learning technology, Facebook uses layers of algorithms to process different components of images with the goal of identifying them. In his post, Dollar gave us a glance at what this means:

The technology classifies the image, states that it appears to contain a person, some sheep and a dog, then detects its core components. That third category, segmentation, is actually very tricky: The algorithms have to learn how to separate precise components of the image from background details or other noise. Facebook said in its blog post Thursday that its technology looks at each pixel in an image and asks simple questions: "Is this pixel part of the sheep?" might be one way of putting it.

Dr. Kris Kitani, an assistant research professor at Carnegie Mellon's Computer Vision Group who's unaffiliated with Facebook, told Mashable that opening segmentation research up to the public is a major milestone.

"In terms of transitioning a basic research idea — semantic segmentation — into a robust tool for public use, this is a significant achievement," Dr. Kitani said in an email. "There is a tremendous of amount of engineering and system development that is needed on top of many basic research results to make things work in the real-world."

So far, computer vision hasn't been foolproof — another reason why more research is needed. Minor distortions to an image, imperceptible to the human eye, have been shown to fool artificial intelligence. Dr. Kitani said segmentation at the pixel level can help."

I do think that the added precision/task of segmentation would help to make image analysis more 'foolproof'... because you are forcing to algorithm solve a harder problem," Dr. Kitani told Mashable.

As you might expect, there are ethical concerns. In the most fundamental sense, we're talking about computers automatically identifying people based on their physical characteristics — in an era of drones and hate crimes, it doesn't take a genius to imagine the ways this could go wrong.

So far, Facebook and Google have required humans to make the final call on putting a name to a face, though: Neither Facebook nor Google Photos, for example, would attach your name to a photo upload without your consent.

And advances in how well the technology work may not be cause for concern.

"This technology could be used to improve the performance of person recognition, but only in the same way developing a more powerful processor could also be used to improve the performance of person recognition," Dr. Kitani said.

Still, the genie's out of the bottle. Photo-identifying technology is here — now comes the task of deciding where it's appropriate.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News