Fake news: How going viral feeds the murky monster of truth

Fake news just got real. Brandon Griesemer, who is from Detroit, was arrested on Friday after making more than 20 phone calls to cable channel CNN and threatening to travel to the news organisation’s Atlanta headquarters and carry out a mass shooting.

So said the New York Post on Tuesday. They called Griesemer a “madman” and a “maniac”, and said his calls had become “increasingly deranged”. “Fake news, I’m coming to gun you all down,” Griesemer apparently told one telephone operator at CNN.

The Post attributed its information to the Atlanta news channel WGCL-TV, who reported that Griesemer had said: “I am coming to Georgia right now to go to the CNN headquarters to f***ing gun every single last one of you.”

By the time the story had started to be shared widely on Twitter, Griesemer had apparently said: “Fake News. I’m coming to gun you all down. F*** you f***ing n*****s”.

Perhaps Griesemer said all of those things – he did, after all, make more than 20 phone calls. Perhaps he said none of them. Or perhaps, as JRR Tolkien said in the foreword to Lord of the Rings, the tale grew in the telling.

There’s some irony in the fact that a news story about fake news is itself susceptible to some of the criticisms that are levelled at news, and how we consume it, and how it is fed to us, and the question of what is and isn’t fake news.

Fake news is everywhere, or at least the discussion of it is. Indeed, Collins English Dictionary last year made “fake news” its word of the year (despite being two words – fake news in itself?). It’s certainly true that it was on everyone’s lips in 2017, especially the President of the United States. Indeed, Donald Trump claimed in November to have actually invented the phrase. “I guess other people have used it perhaps over the years but I’ve never noticed it,” he told TV interviewer Mike Huckabee.

Collins puts the rise of the phrase back to the early 2000s, but it’s much more venerable than that, as broadcaster and journalist Samira Ahmed showed in Bradford on Monday evening. Ahmed, who presents the BBC’s Newswatch programme, was on a panel discussion at the city’s Science and Media Museum, which has curated and hosted a pop-up exhibition on fake news. The exhibition ends this weekend.

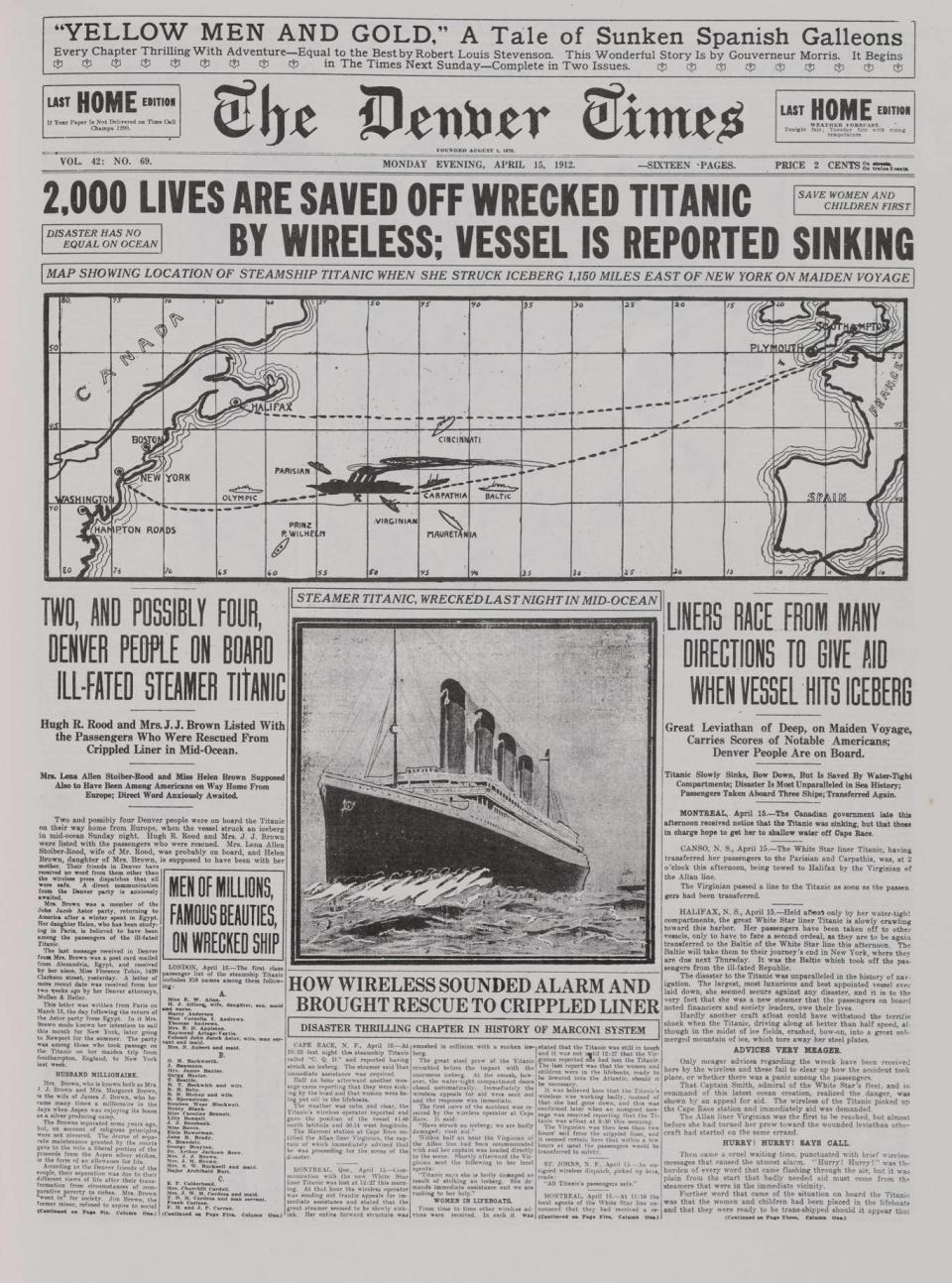

As well as pointing to some of the exhibits in the museum – such as the Cottingley fairies photographs; initial media reports that said everyone on the Titanic had been saved; the photographic evidence that gave lie to official claims that Trump’s inauguration a year ago had been better attended than Barack Obama’s – Ahmed also provided a couple of examples of perhaps surprisingly early use of the phrase. From 1890, she pulled a headline from the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune that proclaimed, “Secretary Brunnell Declares Fake News About His People Is Being Telegraphed Over The Country”, while the following year the Buffalo Commercial newspaper published a leader comment saying the public had no “appetite for ‘fake news’ and ‘special fiend’ decoctions such as were served up by a local syndicate a year or two ago”.

So, nothing new under the sun. But it’s undeniable that fake news has become one of the overriding concerns of the modern age. But what exactly do we mean by it? Well, as was discussed on the panel, there are various degrees of fakeness. Something might be an out and out lie – a Second World War bomber found on the moon, to reference a classic Sunday Sport front page, which we all knew wasn’t true even in those far-off, simpler days of the 1980s. There is fake news for political gain, or more for political discredit: Jeremy Corbyn’s “traingate” row, for example, in which the Labour leader posting a vide of himself not being able to get a seat in a carriage was dogged by claim and counter-claim for weeks.

There’s distraction, as Ahmed pointed out, using an example of a photograph of Canadian Prime Minister wearing Star Wars socks going viral, and distracting us with a big ol’ internet squee from what many people consider Justin Trudeau’s less-than sparkling political record in some areas.

And there’s also the blurring of lines between entertainment and serious news, particularly politics. Where once politicians, especially world leaders, had a measure of distance from the bread and circuses that keep the rest of us going from day to day, now we have images of talk show host Jimmy Kimmel ruffling Donald Trump’s hair, James Corden planting a kiss on the cheek of former White House press secretary Sean Spicer, and Jeremy Paxman marking his last appearance on Newsnight by climbing on to a tandem bike with Boris Johnson and riding off into the sunset.

“I think this crossed the line,” mused Ahmed to the packed debate. “It said that in the end we [media, celebrities and politicians] are all on the same side, and that is not necessarily the side of the public.”

Also on the panel were John Lubbock, from Wikimedia, the charitable foundation that promotes and enables the work of the vast online encyclopaedia Wikipedia; Natalie Kane, curator of digital design at the V&A museum in London, and Dr Gabor Batonyi, representing the peace studies department at the University of Bradford.

Kane had some interesting points to make about how digital design is intersecting the concept of fake news, especially in terms of how new aspects and definitions of “viral” are affecting and involving physical objects. We’re all familiar with an image or video going viral, and this often feeds into the idea of fake news as people share content without really stopping to ask where it’s coming from. But that can be taken to another level, as one item in the V&A’s collection shows: it’s a gun, the components created using a 3D printer. It’s good for one shot, but maybe that’s all that’s required. As another example, Kane cited the “pussy hat” as worn by participants in the global Women’s Marches (and directly referencing Trump’s pre-election “pussy-grabbing” admissions). While guns and hats aren’t fake news in and of themselves, they are perhaps side effects of it, or reactions to it. The files for printing guns, and the patterns for knitting hats, are circulated around the internet, perhaps caught up in the wake of fake news, or at least in the case of the hats, the concept of viral information.

It’s the viral nature of information and how rapidly we share it which can contribute to the fakeness of news. How often do we retweet or share a Facebook post without delving deeply into where it’s come from? And this virality can, in turn, set the agenda for mainstream news organisations. Ahmed points to Prime Minister Theresa May’s coughing fit during her keynote speech at the Tory party conference in October. Ahmed said: “I’m convinced that 15 years ago the BBC would not have led their report on the fact of her coughing. But because social media was talking about it, it became the important point rather than what was being said.”

Interestingly, though, this week saw the latest “trust barometer” released by communications marketing group Edelman, which pointed to a drop in the public’s trust about what they read on social media particularly, and an increase in reliance on traditional media. And yet, we continue to share tweets without verifying them, and trot out the old mantra “don’t believe what you read in the papers”. Perhaps there’s just too much information out there, as Wikimedia’s John Lubbock suggested.

“There’s been an explosion of data, and that perhaps makes us less decisive,” he said. And isn’t Wikipedia part of that problem? It hit its 17th birthday a week ago, marking the milestone with 47 million articles, 181 million pages and 72 million users. The USP of Wikipedia is that anyone – within a certain amount of reason – can contribute to it and edit it. If we’re all editors now, isn’t it millions of people shouting to get their version of the truth across?

“People think Wikipedia is the Wild West,” said Lubbock. “But because Wikimedia is a charity, and we don’t carry advertising, and we’re not for profit, we like to think Wikipedia isn’t contributing to the ‘attention economy’.” In other words, unlike a profit-making website, Wikipedia doesn’t need to keep you on its site after you’ve found what you’re looking for, just to please advertisers.

And because Wikipedia is, theoretically, edited by us all, there’s no one, authoritative voice telling us what to believe: “Truth is something we can create collaboratively.”

But is it? If enough people say a thing is true, does that make it true, even if it isn’t? Perhaps the most pertinent points of the whole evening were made by Dr Gabor Batonyi. The Hungarian historian has seen the direct opposite of the information explosion, which gives us too many options and renders us paralysed by indecision – where there is only state-controlled news.

He said: “People in totalitarian regimes learned how to read between the lines.” In other words, people in strictly controlled societies being fed official news pretty much accepted that what they were being told was probably, at worst, an outright lie, and at best, the varnished, spun truth. Too many versions, we don’t know what to believe. Limited information, we learn to decode the stories and perhaps get a little closer to the truth than is intended for us to know.

Fake news has been with us for longer than Donald Trump would have us believe, and will be around for a lot longer. But perhaps the fact that we recognise its existence, if not always see it for what it is – coupled with a shift in the trust ratio away from social media and back to traditional news outlets – means that we might just emerge from the information explosion with our critical faculties intact.

Fake News at the Science and Media Museum, Bradford, runs until Sunday (scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/whats-on/fake-news)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News