Is the fascinating West Bank home of Munib Musri a shrine – or a gift to a Palestinian state that may never exist?

Munib Musri says that his neo-Renaissance villa and its wealth of carpets, baroque wall coverings, paintings and antiquities is to be a gift to the people of Palestine. He calls it beit filastin – the House of Palestine – and in the basement is a hall to commemorate the suffering and resistance of the Palestinian people.

There is a wall-painting in this cavernous room which portrays a middle-aged man in a keffiyeh leading refugee children out of “Palestine” in 1948. He has a white beard with a brown jacket over a robe and his eyes are staring and appalled. It is a portrait of Musri himself.

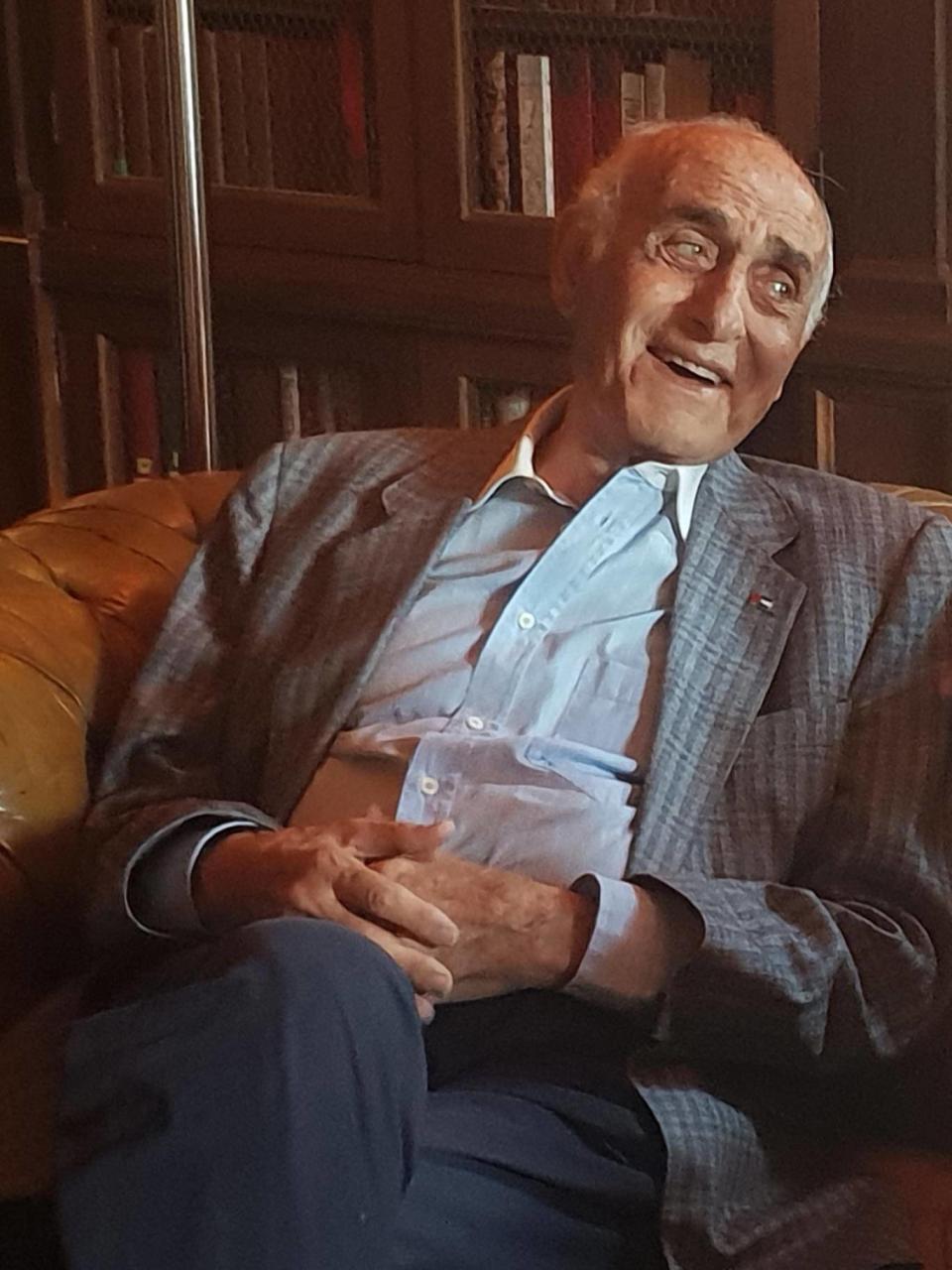

So is this pile – a copy of the Andrea Palladio masterpiece outside Vicenza, its dome just 12 feet higher than the original’s 18 metres – really the house of a state which still does not exist and which may never exist? Or is it a shrine to the dreams of the 84-year-old billionaire who owns it, the eternal optimist amid the eternal Israeli occupation of “Palestine”, one of whose illegal Jewish colonies sits just outside the garden walls, its lights beaming across the villa at night?

Musri – industrialist and owner of conglomerates in telecoms, engineering, construction, banking, you name it – is real enough: tall, athletic, bubbling with outrage, history, anger, honour and a fair amount of name-dropping, as well as quite frightening optimism.

But the ghost of Yasser Arafat is almost as powerful a figure in this echoing palace. His photographs meander along museum walls, with his trademark keffiyeh and that familiar, irritating stubble and protruding eyes that marked him out from his early days as a guerrilla leader. In many of the pictures, a tall and much younger Musri can be observed, flanking Arafat to the right, lingering in the background, an attendant lord – which he most assuredly was, since Arafat trusted him – although he is also a mixture of Prospero and King Lear: wisdom and rage.

“I had faith in the old man, in Arafat,” Musri says rather bleakly when I ask him if the Palestinian leader’s temporary statelet did not reek of the same cronyism and torture as many Arab nations. Musri thought these failings might have been temporary. “Because he was my friend, I always found an excuse for him. And I think you are a bit exaggerating – a bit, Robert – although I think a lot of people saw it the same way. But I always created an excuse for Arafat because overall he was the only one who I thought could do it, the Palestinian state.”

Was this hero-worship, I wondered? Musri has himself turned down the presidency of Palestine, although he has been both a Palestinian and Jordanian minister. After Oslo, he was deeply shocked.

“I was shouting at Arafat and saying, ‘You’re a traitor, you’re this and that’, and he shook me and said: ‘Munib, please have faith in me – that I want you to see that I accepted this to create a state’ … but we screwed up. We screwed up because we didn’t know … When we put the struggle aside, we became fat and we lost the direction.” Started to smoke cigars, I ask cruelly? “Yes, we started to ‘smoke cigars’. But Arafat thought differently. And I believe in what he thought. And that’s why I still hope that Israel will wake up.”

This theme of “waking up” runs through Musri’s conversation like an old thread. I tell him that the great men of Palestine and Israel are old or dying – Edward Said has gone, Uri Avnery has gone, Rabin before his time, “president” Mahmoud Abbas of “Palestine” is around Musri’s age.

“I accompanied Arafat’s body from France [in 2004],” he says. “I was beside his coffin, and I was sitting there, thinking, and I said ‘Arafat!’ – I believed in miracles – and I thought Arafat would wake up and say ‘I’m not dying’. I believed him. I believed him when I met him in 1963 in Algeria when he said … that ‘I will be talking to the whole world that the Palestinians are there to stay’ – and he did [that] in the UN.”

Arafat’s secretary, Bassem Abu Sharif – he who had his hand blasted off by a Mossad parcel bomb in Beirut – wrote down every detail of Arafat’s movements and of his handshake with Rabin.

“Arafat told me, ‘watch me, how I’m going to shake his hand’,” Musri remembers. “And he kept shaking his hand because Rabin had told me ‘I will never shake his [Arafat’s] hand’. If Rabin lived, I think we would have a two-state solution. We made a lot of mistakes – the Palestinians made a lot of mistakes – and this last one [the Fatah-Hamas conflict] is 12 years old, the division, it was so stupid…” At another moment, Musri laments that “we have to get the Palestinian house in order. We must unite.”

But Musri tries to overwhelm regret with optimism. “We are destined to live together, but the Israelis are doing everything to stop this happening – because they want to have the whole thing and eat it. They are very greedy… Because they wanted more and more and because the government, the fanatic religious groups, they want to have the whole thing and it is not going to happen because the Palestinians will do everything in their power not to let it happen. I hope the wounds are not going to open – because the Palestinians will ask [in the future] for the whole state, from the [Mediterranean] sea to the [Jordan] river. We accepted Oslo. When Arafat signed Oslo, I went to see him in Tunis and he was very upset because it didn’t look good at the time – but he convinced me. He said: ‘Munib, you better read Oslo like I read it. It’s an independent state. We gave [up] 78 per cent of our natural land and accepted 22 per cent … to make it happen. Please accept what I’m saying’.”

Musri accepted. “So I’m living on this hope, that we can share the land … If you are living together and with dignity, then you don’t mind if you have a state of 22 per cent or 78 per cent. But we accepted the judgement of Arafat and I hope [the Israelis] will wake up and say ‘Let’s do it!’. I think Mr Netanyahu has every chance to do it and I wish he would do that.”

Musri, I fear, is dreaming. He met Netanyahu during the latter’s first government. “He asked for the meeting and I went and Arafat had encouraged me. I was in Gaza, and Arafat said ‘You go’. Martin Indyk, the American envoy and former AIPAC lobbyist, said he would arrange it. I met Netanyahu at the ministry of defence [in Tel Aviv] and afterwards, he told his aides: ‘Make sure to arrange a meeting every month with Mr Musri.’ I haven’t seen him since. I sent him many messages, even through his secretary. I sent a letter to him, saying: ‘Mr Netanyahu, let’s appear on television – you say what you want and I say what I want – let the people decide’.”

Musri did much secret work to bring about meetings between Hamas and the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank. He believes – or rather, he says he believes – that the talk of Arab frustration at the Palestinians is exaggerated. “It’s a shame what the [Arab] governments have done. But these governments, they come and go, and I hope they will come to their senses… But because I’m an optimist, I always say ‘the Arabs won’t sell us’. Maybe the regimes will sell us, but the ‘umma’ [the Arab ‘community’] will not.”

I’m not so sure. There is something pleasantly naive but also worryingly simplistic about Musri’s reflections on the Arab world. When I noted that no photographs of Saddam Hussein adorned his walls, he replied: “I loved him for his support for the Palestinians – I hated him for his dictatorship.” When I ask about Syria, he responds at once. “I never was in love with the Assad regime, but I support it because the plot has failed. If Syria was overcome and the regime destroyed, I think we would have had ‘Daesh’ [Isis] here.” A good Baathist line, that.

As for Israel, Musri still believes in the “plot”. “They think that by destroying Iraq, by destroying Syria, by destroying Libya, by having this ‘Arab Spring’ bull**** – everybody realises now it was organised for Israel to say, ‘We are the protector, we are the protector of the West and we are the protector of the regimes here.’ They wanted to break up the countries, Syria into 20 or 30 countries, so that Israel could say: ‘I am the contractor to put law and order in this area’.”

Musri hopes – desperately, I suspect – that the Europeans will bravely step forth as the new Middle East peacemaker to take the place of Trump’s America. “They have a responsibility to deliver [on this]… they have to speak their mind. But they want to be away from the problem. We don’t want money. We want our dignity, our independence, we want our state – Europe could do it. Russia will help in doing that, and China…” I admire Musri’s faith, but am amazed that any Palestinian would still put such trust in a Europe which produced not only the Balfour Declaration but the Sykes-Picot agreement.

Musri climbs downstairs, to the underground of his villa where the remains of a fourth century Byzantine church glow beneath the lights, mosaic leaves that turn a darker green when you spray water upon them. What if the Israelis bomb all this one day, in some future military action, a companion asks, including all the treasures and paintings in the villa? “That is why they are uninsured,” Musri says with a smile.

A good guy, as good guys go, and a strong soul – he sleeps, he says, only between 2am and 4am – but I wait to see if Musri’s villa is a shrine or a symbol of hope. There are Muslim artefacts and ancient Christian crosses among his collection, Egyptian columns and olive presses and a Picasso and baroque furnishings, European and Muslim civilisation together.

“The Metropolitan Museum curator – he’s now the curator of the Kennedy Centre – he’s a Jew – he came and spent the night here,” Musri recalls. “And when he wrote in the book next morning, he said it was the most inspiring day of his life.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News