Fibromyalgia: researchers trying to fathom the causes of this painful condition

Fibromyalgia is something of a mystery. It can’t be detected with scans or blood tests, yet it causes lifelong pain for millions of people.

The disease mainly affects women (about 75-90% of cases), causing pain all over the body. Because not all healthcare professionals are adept at identifying and diagnosing fibromyalgia, reported rates of the condition vary greatly from country to country. In China, it affects only 0.8% of people, in France around 1.5%, in Canada 3.3%, and in Turkey 8.8%. Estimates in the US range from 2.2% to 6.4%, and in Russia, about 2% of the population is affected.

People with the condition are often diagnosed if they have longstanding muscle pain, bone or joint pain and fatigue. Fibromyalgia can also cause insomnia, “brain fog”, some symptoms of depression or anxiety, as well as a range of other complaints, including irritable bowel syndrome and headache. Many patients are also hypermobile (“double-jointed”), and there is some overlap with chronic fatigue syndrome (also known as ME).

Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology make it clear that the diagnosis should be made using defined criteria based on the “widespread pain index” (which scores the number of painful regions out of 19) coupled with a symptom severity scale. The diagnosis also takes fatigue, generalised pain, unrefreshing sleep and cognitive symptoms into account. It doesn’t matter if the patient has another rheumatic disease, they can still be diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

The scoring system, recommended by the American College of Rheumatology, is often used in clinical trials, but in the clinic, most doctors rely on detecting tender points in specific places and on excluding other medical conditions, including rheumatic conditions. Unlike say, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, the tests do not show clear evidence of inflammation or autoimmunity (when the body’s immune system attacks itself) and scans are normal.

The lack of inflammation or structural abnormality in muscles or joints – aside from making diagnosis difficult – is the main reason there are no widely accepted or effective treatments. In rheumatic diseases, where we understand the mechanisms that underlie the condition, we have the most effective treatments. In rheumatoid arthritis, for example, we know that much of the inflammation is caused by a cell-signalling protein (cytokine) called tumour necrosis factor and that blocking the activity of this protein switches off the disease in most patients.

A number of possible mechanisms have been proposed in fibromyalgia, including abnormal muscle metabolism, reduced levels of steroid hormones such as cortisol, or abnormal small nerve fibres. But these abnormalities aren’t found in all patients with the condition. As such, they can’t be used as part of a diagnostic test, nor can they help develop treatments.

Some experts have suggested that fibromyalgia may be related to abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system – the part of the nervous system that controls bodily functions, such as heart rate and blood pressure – and how the brain responds to pain signals and reacts to external stressors (such as infections). But there is currently no hard evidence to back up this theory.

Looking for clues

To fill in some of the gaps in our knowledge about this devastating condition, our research team at Brighton and Sussex Medical School is investigating the potential role of the autonomic nervous system and inflammation in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.

For our study, we have two groups of patients: one with pain as the main symptom and the other with fatigue as the main symptom. We also have matched controls – people without the disease, but otherwise similar characteristics – to make meaningful comparisons.

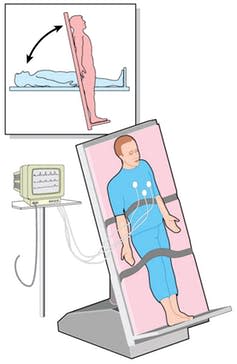

The study is in two parts. First, we will test the patients’ autonomic nervous system using a tilt-table. This involves tilting the person head downwards to see how well their body adapts to this change in posture by changing heart rate and blood pressure (both of which are monitored during the test).

Second, we will stimulate patients’ immune systems with a typhoid vaccine (the normal type used in travellers) and perform magnetic resonance brain scans to look for changes in blood flow and also measure the levels of “inflammatory mediators” (the chemicals the body produces in response to stimuli of this type), to see whether these are higher in the fibromyalgia patients.

Our study should, for the first time, help us to address the question of whether there really is an abnormal brain response to inflammation or infection in these patient groups and enable us to explore the relationship between the abnormal functioning of the autonomic nervous system and fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Fibromyalgia rarely goes away and treatment options are limited. Only by developing a proper understanding of the disease processes underlying this condition will doctors be able to make a clear, positive diagnosis, and most importantly, offer effective therapy.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kevin Davies receives funding from AR-UK.

Jessica Eccles receives funding from Academy of Medical Sciences, National Institute of Health Research, MQ

Neil Harrison receives funding from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council (MRC), Arthritis Research UK, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News