Fin de Partie review – Kurtág's compelling musical testament

György Kurtág’s fascination with Samuel Beckett dates back more than 60 years. After leaving his native Hungary in the wake of the failed 1956 uprising, he attended the Paris premiere of Endgame, or Fin de Partie as it was in the original French version of the play, which had been first performed a few months earlier at the Royal Court in London. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that the notoriously fastidious Kurtág produced any works based on Beckett’s texts. Both What Is the Word and Pas à Pas – Nulle Part are substantial, extraordinary pieces but seem only stepping stones to the opera Kurtág has now composed, which returns to that first encounter with Fin de Partie, and its quartet of characters, locked in a terminal spiral of mutual loathing and dependency.

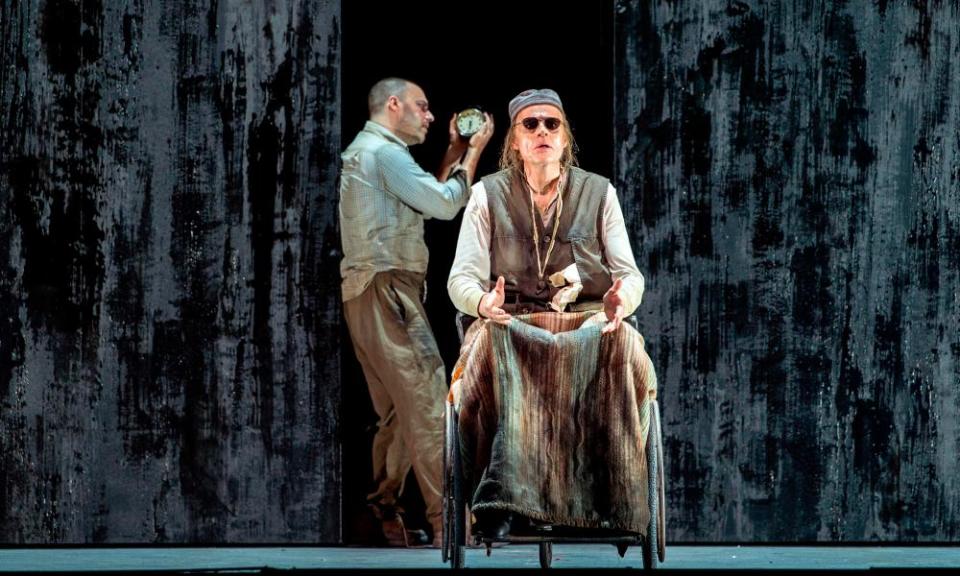

It’s been a long operatic journey and eight years from the original commission. Kurtág has used about 60% of the original French text, omitting some of the repetitions that reinforce the hopelessness of the characters – blind Hamm, who cannot stand, his servant Clov who cannot sit, and Hamm’s parents Nagg and Nell, who have no legs and live in adjoining dustbins. But he’s left their words unchanged, and prefaced the opera with a setting of Roundelay, a Beckett poem from the 70s.

With short pauses between the scenes, Fin de Partie runs for just over two hours, more than twice as long as anything Kurtág has composed before. It’s surely his musical testament – at 92, he was too frail to travel to Milan from his Budapest home. And, as one might expect from one of the greatest figures in the music of the last half century, few new operas are so uncompromisingly distinctive, paying so little heed to anything else in the operatic canon.

The text is set as extended recitative, only rarely erupting into lyricism, and supported by an orchestral score that never uses more than the absolute minimum of instruments. There’s the dramatic directness of Monteverdi and the extreme instrumental compression of Webern – volleys of brass, lonely saxophone solos, tuba growls, snatches of cimbalom and accordion, ripples of harp and occasional surges of warming strings. Just occasionally the orchestra has a brief interlude to itself.

The forensic exploration of the text plays down any moments of black humour; there’s little redemption in the endgames Kurtág depicts so unblinkingly, with three large-scale monologues for Hamm providing the dramatic backbone. But this austerity is compelling, and the rare moments of piercing emotion are transfixing, as when Nagg’s shouts finally fail to summon Nell from her dustbin – his shouts turning first into a wail, then to a piercing scream – or in the only moment when Clov and Hamm sing together, admitting their reliance on each other.

There are rumours Kurtág plans to continue working on the score, but the director Pierre Audi insists what he has staged at La Scala should be considered definitive. Certainly his cool, lucid production, with a design by Christof Hetzer showing the outside of Hamm’s house and changing perspective from scene to scene, perfectly matches the opera’s economy, just as Markus Stenz’s conducting realises every detail of the score with the absolute precision Kurtág’s music always demands.

So, too, do the four wonderfully committed singers – Frode Olsen’s frighteningly austere, unbending Hamm; Leigh Melrose’s gruffly submissive Clov; Leonardo Cortellazzi the touchingly fragile Nagg, and Hilary Summers as Nell, whose gentle, confiding delivery of the Roundelay gets this extraordinary, unforgettable piece under way.

• At La Scala, Milan, until 25 November. Then at the Amsterdam Muziektheater 6 to 10 March 2019.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News