Finding new Everests: The doomed journey up Nanga Parbat, and climbing's endless search for greater highs

Tom Ballard will never climb Everest. Before his death on Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat was confirmed earlier this month, the prodigious British mountaineer would joke that he had been scaling peaks since before he was born – in a way, it was what he was born to do. Aged just 30, Ballard already had some extraordinary feats on his climbing resume, foremost among them his record for scaling all six of Europe’s most challenging north faces in a single winter.

Ballard’s mother was Alison Hargreaves, the first woman ever to climb Everest solo in 1995 and who, equally famously in the eyes of the press at the time, then died descending K2 the same year, leaving behind a husband, Jim, and two children, Tom and his sister Kate. She carried Tom up the north face of the Eiger in the Swiss Alps when she was six months pregnant, and after he was born the family moved to Scotland so Hargreaves could practice on the local crags.

Yet while he followed in his mother’s footsteps in his passion for mountaineering, this fatal Nanga Parbat expedition was also his first attempt at any peak above 8,000 metres. Simply scaling the world’s most famous “big mountains” held no excitement for Ballard – or indeed in Everest itself, which was climbed by more than 800 people in 2018 alone. His father Jim said in 2010: “Tom has no interest in climbing K2 in summer, or [any] routes where there are lots of other people.”

The story of how Ballard came to attempt this particular mountain – the mountain where his body will remain unless and until a recovery attempt is made – is as much about his co-climber Daniele Nardi as it is about the way this extraordinary, exhilarating yet occasionally deadly sport has evolved since Ballard’s mother’s own demise.

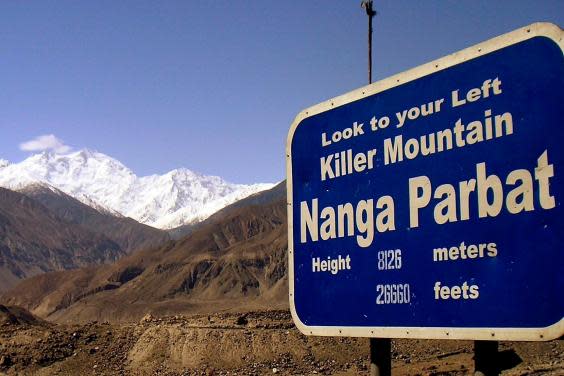

Ballard, 30, and Nardi, 42, were attempting to reach Nanga Parbat’s 8,126m peak via the most direct route, the Mummery Spur. It is an audacious approach, flanked on both sides by towering ice walls that make avalanches a regular occurrence and requiring “mixed climbing” across both ice and rock, a technique beyond even some of the most proficient mountaineers.

[[gallery-0]]

The dangers and challenges are such that no one has ever successfully taken the Mummery Spur route in winter before. And for Nardi, who had already turned back from four previous attempts at the same expedition, that was the point. The Italian was obsessed with the route, says Pakistani climber and tour operator Ali Muhammad, who accompanied Nardi on his 2014-15 attempt but chose to turn back when conditions became too hazardous.

In winter this mountain is so dangerous; very windy, many avalanches and cloudy, with zero visibility. Sometimes you have to stop on the wall because you cannot see where to go – down or up

Nanga Parbat is known as the “Killer Mountain” for a reason, he tells The Independent. “In winter this mountain is so very dangerous; very windy, many avalanches and cloudy, with zero visibility. Sometimes you have to stop on the wall because you cannot see where to go – down or up. Then we have no choice: just hold on until we get better weather.”

It was only three years ago, in early 2016, when an international team of climbers made the coveted first winter ascent of Nanga Parbat by any route, leaving K2 as the only mountain above 8,000m anywhere in the world that has yet to be conquered in winter.

Muhammad says he understands the urge to conquer a mountain in a way that has never been done before. “Daniele and Tom were trying to make a new history in winter climbing,” he says.

But the Mummery Spur, he says, is not just one of the hardest ways to summit Nanga Parbat – it is, in Muhammad’s view, the most difficult unconquered route anywhere in Pakistan, perhaps even the world.

Simone Mori, the star Italian climber among the group that completed the winter ascent in 2016, has described the Mummery Spur as “suicidal”. “It is ice, rocks, snow, and deep crevasses, and that’s just to reach Camp 2. After Camp 2 there are no crevasses. It is all vertical,” Muhammad says.

Nardi and Ballard last made contact with base camp when they were at an altitude of about 6,300m. After a search of almost two weeks, their bodies were found using a high-power telescopic lens by Spanish climber Alex Txikon, another of the successful 2016 ascent team. The families consented to the release of the images, showing two figures and a tent lying close together on a small patch of snow at the bottom of a gully, surrounded by jagged rocks.

“I don’t know why Nardi was trying to do this route, again and again, which is so very difficult, and on a peak where we have already lost one friend last year [Poland’s Tomek Mackiewicz],” says Muhammad. “I will never understand.”

* * *

What changed in the sport of mountaineering between Hargreaves’ generation and that of her son, Ballard, and Nardi? Everest is still Everest, the highest peak on the planet, its height unchanged, more or less, from 1995 to 2019.

Rather what has changed is our perception of what is humanly possible, argues Jake Meyer, a mountaineer who at the age of 21 years and four months became the youngest Briton to scale Everest in 2005. He says that the cultural allure of Everest comes from the fact that it wasn’t climbed at all, that we know of, until Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay as late as 1953.

25 million

The number of climbers worldwide

After that, the landmarks tumbled: in 1975, the first woman to reach the summit. In 1978, the first successful climb without supplemental oxygen. In 1980, the first winter summit. All the way to Hargreaves’ own achievement in 1995. To elite climbers, Everest now has little left to offer.

Like Ballard, Meyer started climbing when he was young, gaining a degree of competency quickly so that his youth alone was basis enough to set new benchmarks and, almost just as importantly, attract the interest of sponsors to make the expeditions possible. He describes a never-ending “arms race” among professional mountaineers to keep pushing the boundaries and achieve things that have never been done before, or at least do them in a way that is new – playing with the “semantics”, he calls it.

“One of the reasons why I was able to get funding was because I was young and chasing records, because at that time it was still relatively uncommon,” he says. “I think if you went back to the same people today at a similar age, I think you would really struggle [to get sponsorship].”

Nardi was keenly aware of this competition, and indeed saw it as integral to the sport. Pakistani mountaineer Karim Shah Nizari quoted him in a tribute after his death by saying: “He always said, ‘A climber is someone who climbs new routes’.”

In a modern world of social media and round-the-clock connectivity, that urge to open up new frontiers and explore the world’s last wildernesses may be appealing – but it is also one “that has always been there” as a driving force for the great historic mountaineers, Meyer says.

The difference now is that with Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, hundreds of thousands of fans around the world can follow their favourite climbers’ expeditions in real time.

Nardi’s official Facebook page had more than 100,000 followers at the time of his death. The latest updates in the search and rescue operation for the pair were distributed direct to supporters by Stefano Pontecorvo, the Italian ambassador to Pakistan. And Alex Txikon, who has more than 58,000 Facebook followers, shared dramatic photographs and video from the frontline of the search.

Could this new exposure, and the fact that sponsors pay a lot of attention to mountaineers’ status as modern influencers, be another factor leading them to take greater risks? It’s a question Meyer poses. “Everyone is so aware of what everyone else is doing,” he says. “You have to be doing bigger, badder, more awesome and, as a result, slightly dangerous things to keep up? I think that if people are treating it like that, then it is a race to the bottom.”

If mountaineering and climbing have taken an edgier and more extreme turn in the past 20 years, it isn’t just on new media formats that people are taking notice. Up until the turn of the century, the sport was considered fodder for low-rent thrillers like Vertical Limit (2000, starring Chris O’Donnell), Cliff Hanger (1993, Sylvester Stallone) and The Eiger Sanction (1975).

Something changed around the time of North Face (2008), a critically acclaimed German film about the competition to scale the most dangerous ascent of the Alps. In 2010, 127 Hours about mountaineer Aron Ralston’s fall down a canyon in Utah was runner-up for six Academy Awards. Finally, this year the suspenseful Free Solo, about Alex Honnold’s successful climb up Yosemite’s El Capitan rock wall without a rope, won the Oscar for best documentary.

I don’t go to the mountains because I have a death wish. On the contrary, I go there because that’s where I feel alive

Jake Meyer

Climbing is now officially cool – and there are figures to back up the assumption that young people who might once have been inspired to take up skate- or snowboarding are now turning to their local bouldering gym instead. In North America, indoor climbing is set to be a billion-dollar industry by the year 2021, according to the Climbing Wall Association, with a record 43 new climbing gyms opening up across the US in 2017.

The International Federation of Sport Climbing estimates 25 million people are climbing regularly worldwide, with the number of young competitors in the UK up 50 per cent in the past five years. And in another landmark for the sport unthinkable a generation ago, sport climbing will feature at the summer Olympic Games for the first time in history next year at Tokyo 2020.

“It’s amazing to see how much it’s changed over my career, and we’re talking 20 years since I watched the new millennium dawn over Kilimanjaro,” Meyer says. “It’s incredible, fantastic, and it’s an inspiration.”

* * *

As the sport’s popularity continues to grow and its elite members keep pushing the limits of what’s possible, a point will be reached where mountaineering must pause and take stock of the element that makes it stand apart from other pursuits – the extraordinary risk to life involved.

The Italian climber Mori has been the most outspoken in the community since Ballard and Nardi’s deaths, telling The Times newspaper that “if we continue to say they were just unlucky, the risk is someone will die there next year”.

And if the trend continues for increasingly young climbers to seek out the road less travelled, in search of new and more impressive feats, the dangers posed are not just from the mountains themselves.

Nowhere is this more evident than with Nanga Parbat. In 2013, a major terrorist attack was launched at the mountain’s base camp, itself a remote outcrop 4,200m above sea level that can only be reached on foot. The attack, claimed by the Pakistani Taliban, killed one local guide and 10 international climbers, among them an American-Chinese citizen who was believed to have been the prime target for the gunmen in a kidnapping gone wrong.

In 2013 at Nanga Parbat basecamp a terrorist attack by Pakistani Taliban claimed the lives of one guide and 1o international climbers

After the massacre, the gunmen walked for five hours before eating breakfast at a village and dissipating in the small hours of the morning. An AFP report a year on from the attack suggested most, if not all of the perpetrators remained at large. The 2013 attack aside, the Gilgit Pakistan region where most of the country’s biggest mountains lie is generally very safe, far from the restive western border with Afghanistan.

Trekkers and climbing enthusiasts are starting to return to the region in larger numbers and can expect encouragement from visa officials and a warm welcome from locals, says Karra Hadri, spokesman for the Alpine Club of Pakistan, the sport’s governing body in the country. Hadri, who remembers Ballard from the time when he visited Pakistan as a toddler with his mother and was carried up to K2 base camp on a porter’s back, says last year there were more than 40 major expeditions in Pakistan – up from just one or two in the years after the 9/11 attack.

But he is concerned that growing numbers of young people will come to the country seeking adventure and put their lives in danger. He is calling for a change to the regulations for permits, so that climbers must prove themselves on smaller peaks before attempting any of Pakistan’s five 8,000m-plus summits.

“Mountaineering in Pakistan, especially above 8,000m, can be very difficult compared to the rest of the world,” he says. “We still have many mountains that have not been climbed, but youngsters need to know the risks. They should have a lot of skill, a lot of experience, and much budget. And they should go in a group, not just one or two alone.”

Hadri was closely tracking the progress of the search operation over the past two weeks and was “very sorry to hear” about Nardi and Ballard’s fates. “Tom’s mother was a brave lady,” he adds.

Ballard is survived by his sister, Kate, who posted a message on Facebook after he went missing thanking people across the world for their “love and thoughts”, and by his girlfriend Stefania Pederiva, who wrote: “I will find you in nature, in the rivers, in the trees, in the mountains, you will always be my most beautiful rock.”

Nardi is survived by his wife Daniela and a son Mattia, who is just six months old. And while the sport mourns two of its most promising sons, climbers as a whole are stoic about the risks they take in pursuit of their passion. Meyer, who last year joined an elite group of only 10 Britons to have scaled K2, says he cannot imagine removing the element of danger from mountaineering, despite having, like Nardi, young children at home.

“I don’t go to the mountains because I have a death wish. On the contrary, I go there because that’s where I feel alive,” he says. “If you remove the element of risk completely, then what you are left with is almost every other sport. Having children didn’t change my desire to want to go, but what it did was it gave me three times the reasons to come home safe.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News