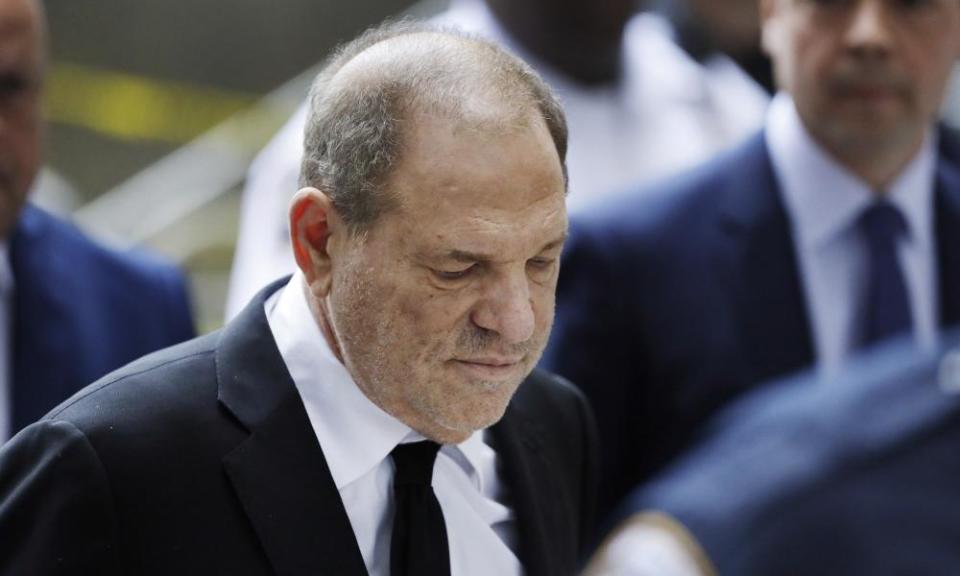

Fixing a tattered reputation like Harvey Weinstein’s is dirty work, but pays so well

Odious Harvey Weinstein is, of course, chief villain of the brilliant and deeply satisfying new book, She Said, by the New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. It details how, in 2017, they finally unmasked the alleged – his trial is pending – serial rapist. Shortly after publication, however, much interest has alighted on another, less familiar figure in this story, who was once as fully committed as Weinstein to silencing and shaming survivors, intimidating reporters and rebuilding his good name: a US lawyer called Lisa Bloom.

At the same time as it offers inspiration and guidance to investigative reporters in pursuit of powerful bullies, She Said – with its startling new evidence about Bloom’s involvement – also supplies a priceless introduction, for novices, to the business of reputation management.

How is it that some obvious shits still prosper, or make rapid comebacks as deferred-to public figures, despite persuasive rumours or actual evidence of, say, sexual molestation, bullying and serial dishonesty? How do their misdemeanours sometimes descend so swiftly from the top of Google searches? Some of that will be attributable to luck, time or the process whereby, as some of our leading douches have demonstrated, continually overlaid offensiveness, on a vast and sufficiently public scale, will effectively neutralise decades of misconduct. How many times, after all, can one react to the transformation of a proved GBH plotter, racist, liar, sexist and idle, incontinently shagging idiot into a national leader?

But Bloom sets out, in an email revealed by Kantor and Twohey, the potential benefits of employing reputation professionals when the concealment of specific wrongdoing is urgent or less amenable to denial.

A woman’s advocate, with – in December 2016 – a still-intact reputation as a feminist, Bloom offered her services to Weinstein; allegations of his sexual misconduct were circulating. Much of the relevant memo, which deserves to be read in full, features slurs against Rose McGowan, one of the earliest and bravest of Weinstein’s accusers, alongside assurances that Bloom understands, from her experience representing survivors, just how to deal with “the Roses of the world”.

Options for shutting down McGowan’s accusations include, Bloom suggests: (1) falsely befriending her; (2) “counterops”, an “online campaign to push back and call her out as a pathological liar… we can place an article re her becoming increasingly unglued”; (3) a scary cease and desist letter; and, more positively, (4) and (5) a phony show of repentance from Weinstein – “this is very doable” – along with ostentatious, targeted philanthropy, to prove that Weinstein, the predator of the “Roses of the world”, is on the contrary a hero: friend and benefactor to the Roses of the world.

For instance, Bloom says: “Start the Weinstein foundation, focusing on gender equality in film, etc.” Finally, Bloom proposes working with a reputation management company to mess with Google searches: “Your first page of Google is key… Easy to do.” She was hired, for $895 per hour. Only much later, after intercessions on behalf of Weinstein that included a threatening appearance in the reporters’ newsroom, did Bloom describe her involvement as a “colossal mistake”.

This expert in counterops blamed the mistake on her “naivete”. It has not advanced her repentance journey, either, that the true extent of Bloom’s concern for survivors was revealed in the same week that Margaret Atwood’s vicious collaborator, Aunt Lydia, reappeared in The Testaments. “What good is it to throw yourself in front of a steamroller out of moral principle?” Lydia reasons. “Better to hurl rocks than have them hurled at you.”

As for Weinstein: he did pay for McGowan to be falsely befriended by an agent from the Israeli firm Black Cube; he repented, lavishly and, in retrospect, hilariously – “I’ve asked Lisa Bloom to tutor me”; he pledged $5m for a scholarship fund, at the University of Southern California, for female film-makers, “named after my mom”.

While undetectability, the heart of reputation management, makes it hard to know which of our most improbably respected names owe their survival to a Bloom-like playbook, her focus on philanthropy as a redemptive tool ought to establish, finally, for organisations yet to grasp this point, that offers of money from compromised or suspect donors mean they are being used.

In Weinstein’s case, intended beneficiaries were, effectively, cast as accomplices in Bloom’s Rose-persecution schedule. But at other times they might be helping purge historical links with, say, Vladimir Putin, with fascist organisations or with discreditable financial practices. You sometimes get the impression that, usefully for donors and their advisers, complacency on this point, and carelessness about complicity, is most likely in organisations whose motives are unassailably pure and high-minded.

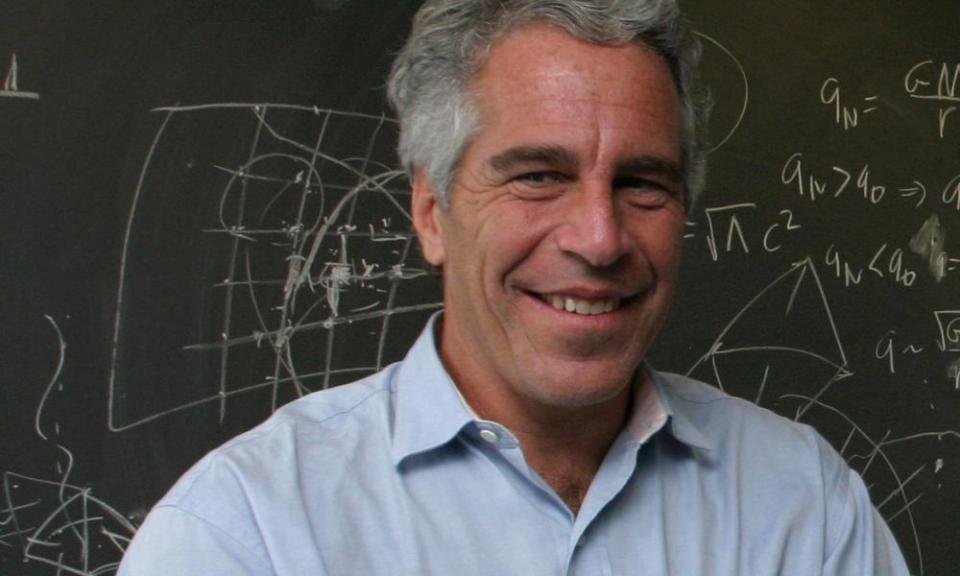

For some reason, some of the world’s most brilliant academics happily accepted invitations and visits, as well as funds, from Jeffrey Epstein, the relentless paedophile, founder of the Epstein Foundation, and friend of Prince Andrew.

Although students at USC successfully campaigned to reject Weinstein’s gift, numerous male scientists, including those at MIT’s Media Lab, reportedly the recipient of $7.5m, accepted swag from the Epstein Foundation, thus helping position its creator, in websites that popped up on Google, as an unworldly brainiac. His customary female attendants could be, it appears, overlooked by the truly gifted and talented.

A female academic recalls, in Ronan Farrow’s report, being concerned for the wellbeing of two young women accompanying Epstein when he visited MIT in 2015: “They were models. Eastern European, definitely.” The Media Lab director has now resigned. But its co-founder, the digital utopian Nicholas Negroponte, says he’d take Epstein’s cash all over again. “We all knew he went to jail for soliciting underage prostitution, but we thought he served his term and repented.”

And with that, thanks to Epstein, yet another reputation falls due for professional refurbishment. Prince Andrew might know someone.

• Catherine Bennett is an Observer columnist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News