After the Florida school shooting, it's no wonder the youth are turning to protest

Commit these names to memory, because you’re going to need them.

Alyssa Alhadeff. Scott Beigel. Martin Duque Anguiano. Nicholas Dworet. Aaron Feis. Jaime Guttenberg. Chris Hixon. Luke Hoyer. Cara Loughran. Gina Montalto. Joaquin Oliver. Alaina Petty. Meadow Pollack. Helena Ramsay. Alex Schachter. Carmen Schentrup. Peter Wang.

The students and their teachers and coaches who died on Wednesday 14 February at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. You’ll need to remember the date and place as well. Because your children, and your grandchildren, will be studying them in their history lessons.

But not just the names of those who died at the hands of 19-year-old Nikolas Jacob Cruz. The names of those who survived, who spoke out, who set in motion the chain of events which we will look back upon and realise we were living through history.

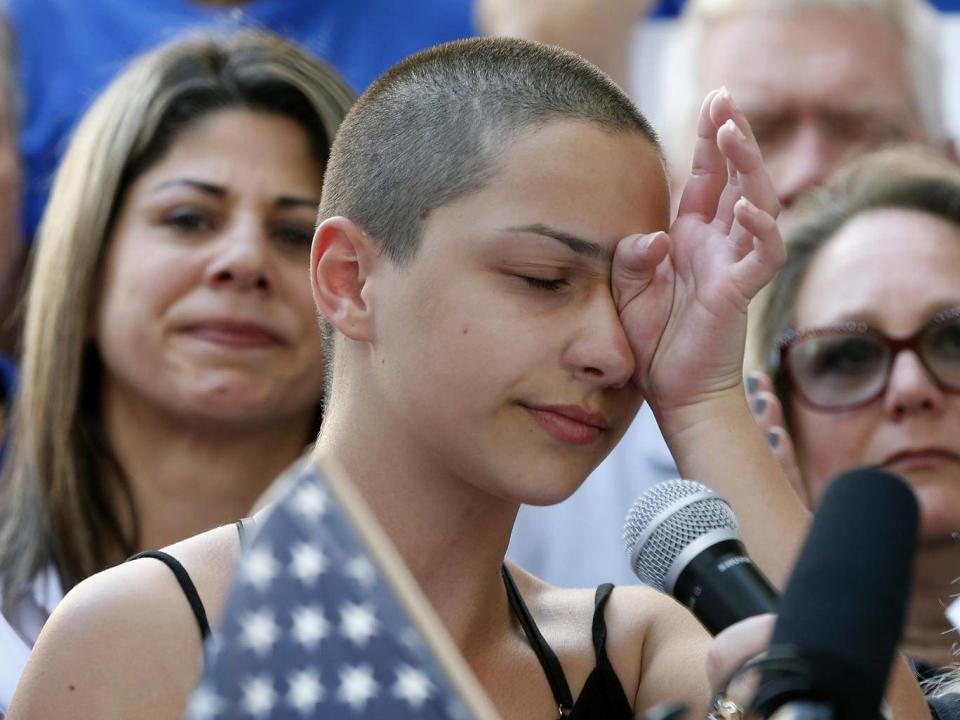

Names such as Emma Gonzalez, one of the survivors of the shooting, whose quietly fierce speech decrying President Donald Trump and US lawmakers for their close associations with the National Rifle Association galvanised thousands of young Americans to do what had almost become unthinkable: demand gun control, and the end of the widespread carnage wrought on the children of the Land of the Free by the ubiquity of high-powered firearms.

Within a week of the shootings, rallies were being held, driven by young people. School and college walkouts are scheduled for 24 March, which will include a march on Washington, and 20 April, the 19th anniversary of the Columbine school massacre.

If you think that this means nothing, that it’s just a bunch of kids letting off steam, that it’ll amount to precisely zero, then you’re a fool. If you’re one of those who has publicly decried these young people, who has spread fake news claiming them to be actors, or brainwashed by the left, then you’re a monster. If you were sitting in the Florida House of Representatives in Tallahassee on 20 February, just six days after the shooting, and you voted to reject the bill to ban assault weapons, then expect to see your names as a footnote in the history books, too. But for all the wrong reasons.

Major societal change has always been brought about by young people. For future historians, there’s probably a neat symmetry in the fact that the groundswell of support for gun control is rising as we approach May, which will mark the 50th anniversary of the start of one of the biggest mass protests in history. Which, of course, was begun by young people.

The protests led to strikes and practically brought France to its knees, and spread across Europe and the rest of the world. They started on 22 March 1968, when students, poets and writers, and far-left groups occupied buildings at Paris Nanterre University in protest against growing class divisions in French society, university funding and the growth of capitalism and consumerism.

The police were called and the protesters left peacefully after making clear their demands. But trouble rumbled on for the next two months, and the university closed its doors because of the level of protest on 2 May. Sorbonne University held its own event the next day to support the students threatened with expulsion, and by 6 May more than 20,000 students and lecturers marched on the Sorbonne, clashing with police. The rally descended into running battles, with students ripping up street furniture to create barricades as police charged with batons and teargas.

Perhaps it was the images of police brutality which galvanised the rest of the country, but more protests followed and factory workers got swept up in the fervour, closing down industrial sites despite their unions’ attempts to get them back to work, instead demanding more rights for the working class.

So widespread was the unrest across France that President Charles de Gaulle reportedly fled the country, fearing nothing less than a second French revolution. He was gone only a matter of hours, to Germany where he met with the leaders of the French military to make sure he had their support, but for those hours France was effectively without a functioning government.

On 30 May, four weeks after the university at Nanterre had closed its doors, De Gaulle announced a general election for 23 June, and the protests subsided… apparently with the added threat of the President instituting a state of emergency if they didn’t, with the military poised to march into Paris. He won the 1968 election, but resigned in 1969, and died the following year.

There must have been those in Paris, just about 50 years ago, who dismissed the actions of a handful of students as a flash in the pan. Perhaps they thought they’d been infiltrated by the hard left. Perhaps they even thought the most vocal of them were merely actors.

Throughout history, it’s been young people who have paved the way for meaningful change. We rightly remember Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat for a white passenger on a bus in Alabama in December 1955, but nine months previously Claudette Colvin did exactly the same thing, also in Montgomery, and was arrested. She was just 15 years old.

In 2010, aided by social media, young people in North Africa and the Middle East prompted the waves of largely peaceful demonstrations against the oppression and authoritarianism of their governments in a movement that became known as the Arab Spring.

In 1989, students teamed up with veteran dissidents to protest against the one-party government in what was then Czechoslovakia. The Velvet Revolution ushered in a period of major reform, the institution of a democratic government, and the creation of two whole new countries. The Berlin Wall had already fallen; the map of Europe was changing. The old ways, and the men who advocated them, had been found wanting.

Consider these words: “There was a time long, long ago, we understand, when age and experience brought the kind of wisdom which younger men could admire and envy and seek to emulate. The old men held their position of power because they could show that age had brought them breadth of understanding and an enriched vision of the way ahead.

“It is just one of the curiosities of the modern world that age and experience have brought to so many only the sickness of self-despair and the desire to escape from the realities of existence if not through suicide then by bolting down a variety of intellectual and emotional hidey-holes.

“It is the claim of my generation that we can understand the causes which have driven our elders to this situation and can pity them.”

They were written by journalist and broadcaster George Scott in his autobiographical book Time and Place. They could have been written today. The book was published in 1956, when Scott was 31.

Just about a year ago, I wrote a piece for The Independent which was the most widely shared thing I have ever done. It was about Generation X, that often-forgotten cohort between the Baby Boomers born in the post-war period, and the millennials, who came of age in the year 2000.

Don’t worry, I said, referring to the ills of the world. We’re Generation X. We’ve got this. And maybe I was half right. Because while my generation did a lot in laying the groundwork for a better world, it’s not our place to make that world.

Those Parkland kids, and their peers. Generation Z; call them what you will. It’s their world and they’re going to be the ones that build it. They’re building it now. They’re saying enough is enough. On the day of the Parkland massacre, I would have said with a lot of conviction that you’ll never separate Americans and their guns, that they’re too enmeshed, and for too long.

A week later, after seeing the determination, bravery and refusal to capitulate from those young people, I wasn’t so sure.

From the student protests of Paris in 1968 to the Velvet Revolution in 1989, the biggest change has been born out of energy from young people allied with experience of older generations. In Paris the students lit the touchpaper; the workers in the factories fanned the flames. And that’s what my generation has to do.

We have to stand aside and let this blow up, and then offer our support and help. That’s how it works, that’s how it’s always worked. From #MeToo to #TimesUp to #NeverAgain, the baton has been officially passed.

Your children and your grandchildren will be learning about 2018 in school. And if you want the history books to treat you kindly, now’s the time to start doing the right thing.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News