Frank Field: I back the ban, it’s over to Uber to show it can raise its standard

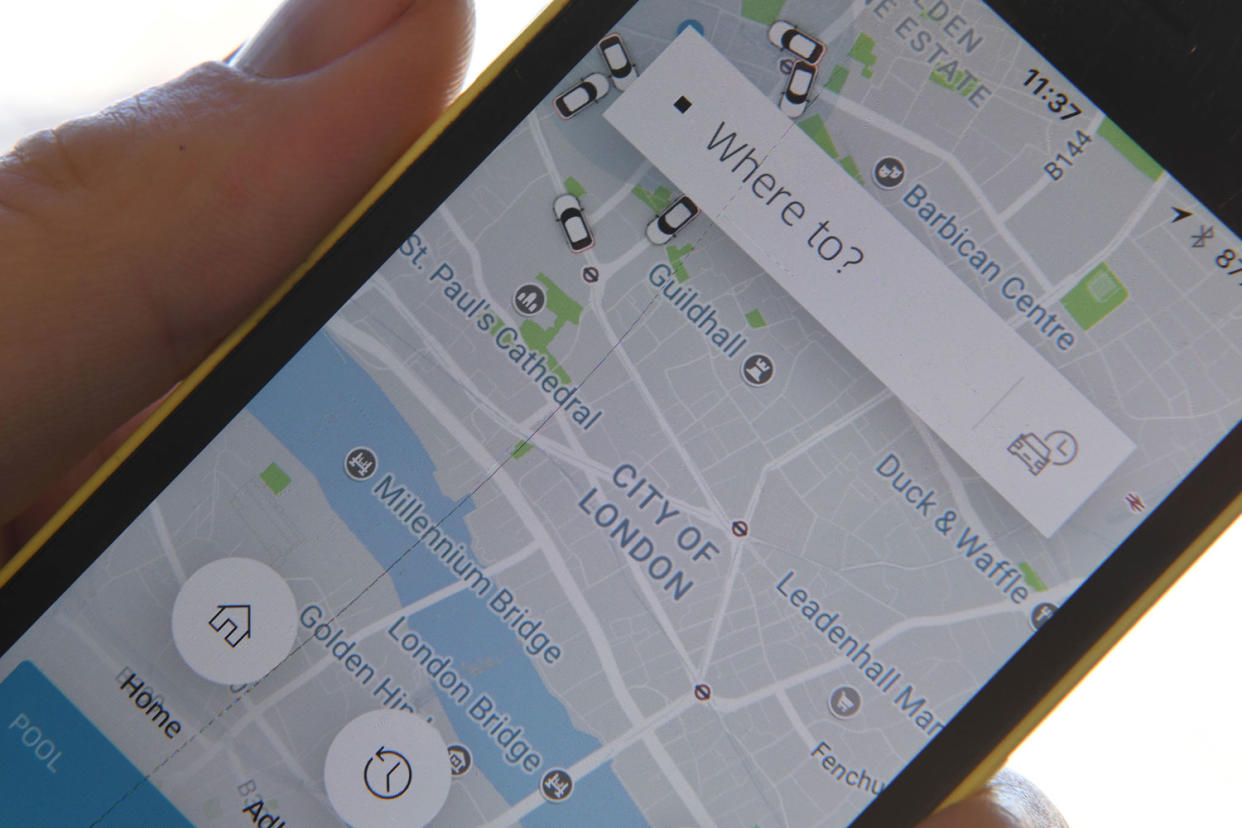

The future of London’s transport network was turned upside down on Friday when it seemed possible that Uber might disappear from the streets. So too, in fact, was the whole “gig economy” on which millions of people now rely for work, goods, and services.

While black cab drivers rejoiced, more than 700,000 people signed a petition calling for a reversal of the decision taken by TfL to strip Uber of its licence. I support its decision.

In its wake, Londoners debated what the rise of Uber has meant for passenger safety, congestion, drivers’ living standards and competition for taxis and minicabs. There was also talk of a long court battle between Uber and TfL.

Now the debate has settled down: Uber is hugely popular among Londoners but it has failed to comply with certain rules and, as such, is not considered a fit and proper operator. Having had time to reflect, Uber now says it is willing to negotiate with TfL on the improvements it must make on safety and pay, for example, to retain its licence. This already represents real progress from where we were three days ago.

What happens next will carry lessons for the rest of the country, as well as those cities across the world where Uber operates, or wishes to. I offer here a route map for TfL and Uber to follow, not only to settle their own dispute but also to establish London as an example for transport networks everywhere.

The first step must involve TfL making clear to Uber that it has not totally repudiated the company. It should remain open to a fresh application for a new licence conditional upon Uber making real changes to its current model.

The guarantee TfL made to Uber’s 40,000 drivers — that they can continue operating until the dispute has been settled — is a welcome opening move. Many of those drivers have taken out costly hire-purchase agreements to obtain vehicles that meet Uber’s requirements. Therefore, despite being classed as self-employed, their fortunes are bound up with that of the company. An immediate removal of work would have disastrous human consequences.

For its part, Uber must now show TfL it means business by withdrawing its threat of a lengthy legal battle over Friday’s decision. The company should instead ask TfL this week to present it with a set of licensing criteria by which it needs to abide in order to be deemed a fit and proper operator.

Then comes the most crucial part. TfL must initiate a major upgrade of the current regulatory environment so as to provide the best service for passengers without placing drivers at a disadvantage. This will involve the construction of a totally new set of regulations, showing the world that London welcomes innovation and wishes to encourage entrepreneurialism but is also serious about passenger safety and protecting the living standards of drivers who represent the vulnerable underbelly of the labour market.

A game-changing move here has already been made by Transport Minister John Hayes, through the creation of a new working group on taxis and private hire vehicles. The working group, which meets tomorrow for the first time, will review existing regulations on passenger safety and drivers’ pay and conditions, and make recommendations for future policy. It was set up to act on findings which I presented to Hayes during a Commons debate in July, on what Uber’s rise tells us about the gig economy.

Andrew Forsey and I found in our investigation that some drivers have enjoyed working with Uber in a flexible relationship governed by few regulations. Likewise, millions of passengers have made the most of having a low-cost, convenient service at the touch of a button. But our investigation also revealed that there are drivers with young families, relying on Uber as their sole source of income, who are taking home less than £5 an hour — they are not covered by the National Living Wage or other worker protections, as they are classed as self-employed. Both industry and the welfare state have yet to come to terms with the importance of the National Living Wage strategy, at a time when more people work in the gig economy.

Inadequate regulation has both put the safety of some passengers at risk, and allowed Uber to flood the market with huge numbers of new drivers. For existing drivers, this has resulted in a cut in living standards – more cars on the road mean there is less work to go round. It was on the basis of these findings that we recommended to TfL it should only renew Uber’s licence if the company incorporated minimum standards into its business model.

We remain of the belief that those minimum standards must be sacrosanct, not optional — Uber needs to show TfL that it has taken the measures to guarantee passenger safety. Likewise, TfL must ensure that all drivers who are logged in and available for work take home no less than the National Living Wage.

In the coming weeks, the working group will seek a new framework on safety and pay, which gives TfL the tools it needs to strike a balance between freedom, flexibility, protection and minimum standards. Friday’s decision shows that a rebalancing of regulation is badly needed in the gig economy.

Over the same period, two Commons Select Committees — Work & Pensions, which I chair, and Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, chaired by Rachel Reeves — will be thinking about what changes are needed to enshrine this new balance in law.

Matthew Taylor’s report on modern employment, which the Prime Minister commissioned on the back of the first report Andrew and I published on the gig economy, offers the basis for reform. But we must ensure the protection of the National Living Wage forms the cornerstone of any new settlement for low-paid drivers.

We hope to reach a position in a few weeks’ time, when Uber is able to advise on how best to strike this new balance. For the sake of passengers and drivers, the firm must show first that it is capable of incorporating a series of minimum standards within its business model.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News