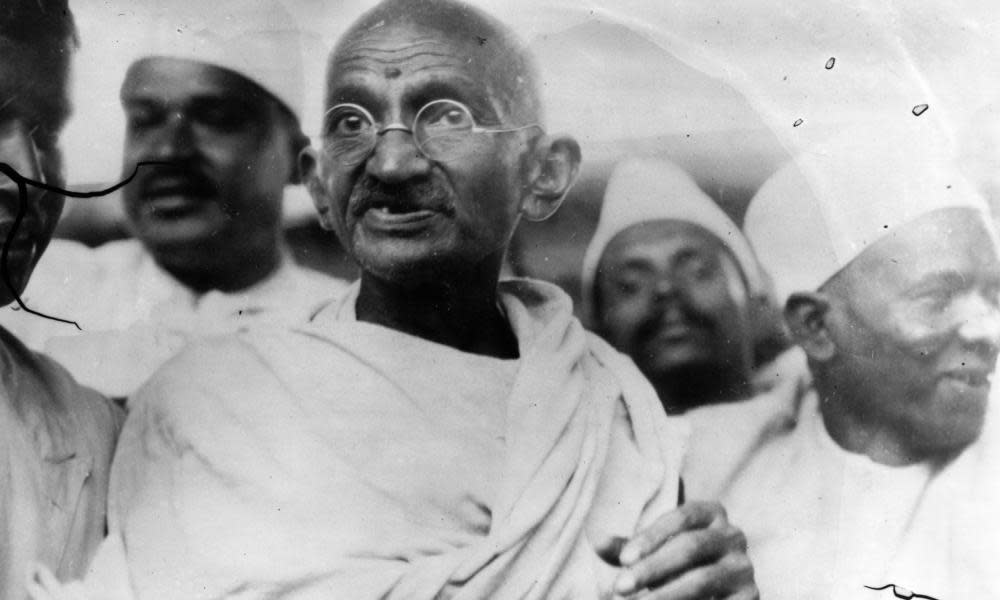

Gandhi scholar quits Indian university after nationalist pressure

An Indian biographer of Mahatma Gandhi will no longer teach at a university in the independence leader’s home state after the institute came under pressure from critics including Hindu nationalist student groups complaining his work was “anti-national”.

Ramachandra Guha, an Indian public intellectual whose works have covered cricket, the environment, contemporary Indian history and the life of Gandhi, had been announced in September as the newest faculty member at Ahmedabad University in Gujarat state.

Last week, after a student union affiliated with India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party complained about Guha’s appointment, the writer said on Twitter he was no longer joining the university.

“Due to circumstances beyond my control, I shall not be joining Ahmedabad University,” he wrote, adding: “May the spirit of Gandhi one day come alive once more in his native Gujarat.”

Due to circumstances beyond my control, I shall not be joining Ahmedabad University. I wish AU well; it has fine faculty and an outstanding Vice Chancellor. And may the spirit of Gandhi one day come alive once more in his native Gujarat.

— Ramachandra Guha (@Ram_Guha) November 1, 2018

The Guardian understands the newly established university faced political resistance over the appointment and asked Guha to defer the start of his post until after parliamentary elections, scheduled to take place before May. Since the appointment had already been announced, Guha decided not to take up the post rather than delay its commencement without explanation, sources said.

His selection as a professor of humanities had earned the ire of members of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), a student group affiliated to the ruling party of the prime minister, Narendra Modi.

A memorandum penned by the group and addressed to the university’s vice-chancellor said Guha’s work was “critical of India’s Hindu culture”.

“His such writings have encouraged divisive tendencies, alienation in the name of independence of the individual, freeing terrorists in the name of independence of the individual, and separating Jammu and Kashmir from the Indian union,” they wrote.

The ABVP, which claims to have more than 3 million members, has become more prominent on Indian campuses since Modi’s election in 2014, regularly clashing with liberal and leftwing student groups and disrupting events they deem anti-Hindu.

Ahmedabad University denied being pressured into any decision by the ABVP.

Guha has been critical of the Modi government but also its main opposition, the Congress party. He famously described India as a “50/50” democracy, but two years ago revised the democratic quotient in the Modi era downwards to 40/60.

Groups such as PEN International have warned of “a rising tide of violence, impunity, extended pre-trial detentions, and surveillance” in India since Modi was elected, though others, including Guha, have pointed out that previous governments have also shown varying degrees of intolerance to dissent.

Yet no government in recent decades has enjoyed the parliamentary majority of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party nor had its zeal or mission to explicitly reshape the country to put Hinduism at the political and cultural centre.

Some prominent commentators reacted with dismay at Guha’s apparent unwillingness or inability to teach in Ahmedabad, the city where Gandhi went to high school and established his base after returning from South Africa.

“It’s come to a stage that an accomplished historian of modern India can no longer teach where he wants to in the country,” wrote Sushil Aaron, a journalist and commentator.

Modi’s government has also exercised its right to change the composition of state-funded cultural institutions to include appointments of those closer to its worldview.

Last week, it raised eyebrows by appointing the bombastic television host Arnab Goswami to the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library board. Another public intellectual, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, had recently quit the board citing political pressure.

A major Delhi institute, Jawaharlal Nehru University, whose vice-chancellor was chosen from a list created by a government agency, last week appointed a Hindu nationalist activist as an honorary professor.

Rajiv Malhotra, a former entrepreneur turned writer, has gained a large following for his criticism of Hindu scholars, especially foreign ones, some of who he claims have been driven to studying, and in his view, eroticising aspects of, Hinduism because of repressed sexual desires.

His work has earned him a large following among Hindu activists but also scorn from religious scholars, with one theologian at Princeton in the US accusing him of plagiarism and “a lack of academic integrity”.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News