‘GEEEETTAAOUTTOFIT!’: Carl Barat on the story of The Libertines’ ramshackle, rebellious debut Up the Bracket

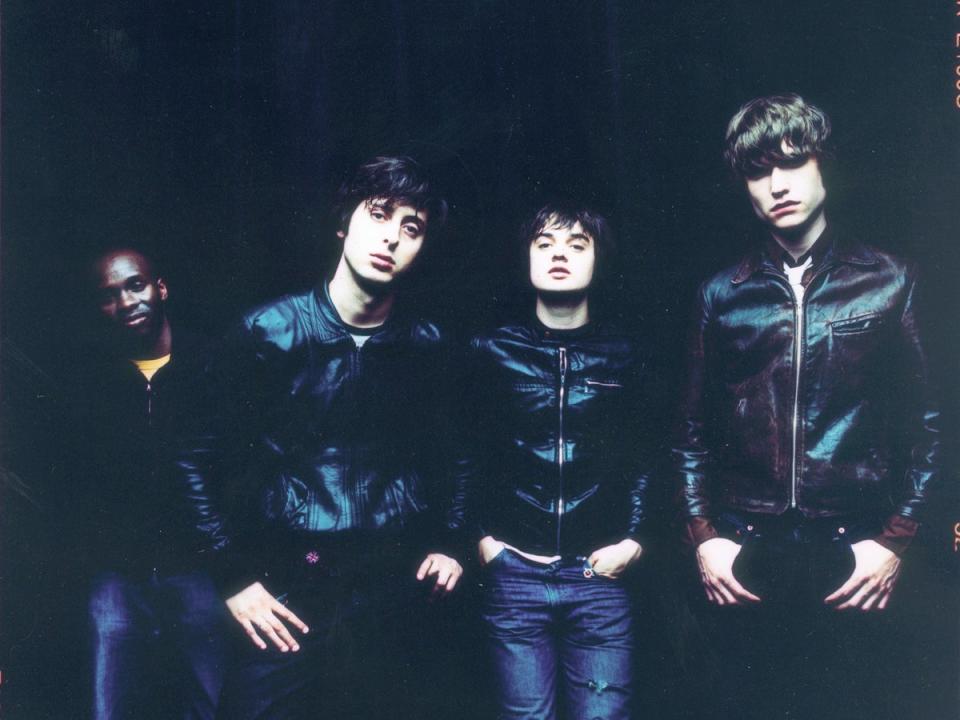

It started with a blood-curdling scream: “GEEEETTAAOUTTOFIT!” Pete Doherty’s visceral howl opens “Up The Bracket”, the lead single from The Libertines’ debut album of the same name. Released 20 years ago, on 21 October 2002, the record was an unruly, triumphant beast that revived British guitar music from its post-Britpop doldrums and gave the country an answer to the New Rock Revolution being led in the United States by The Strokes and The White Stripes. The accompanying music video made bright red military tunics an instant indie fashion staple, while a nondescript alleyway in Bethnal Green became a site of pilgrimage for dedicated fans. “That’s still going on now,” notes Carl Barât, whose volatile partnership with Doherty formed the nucleus of the band. “I think the council cover over [the graffiti] every year, but it keeps coming back. What a funny time that was. The video concept was, ‘We’ll bring the cameras round and leap around the house pretending to play guitars.’ Halcyon days!”

Barât is sat in the bar at The Libertines’ hotel and studio The Albion Rooms in Margate, sipping from a mug of tea. On “Death of the Stairs”, Up The Bracket’s second track – and still his favourite – he once sang: “Don’t bang on about yesterday, I wouldn’t know about that anyway”. Today, though, he’s in the mood to reminisce about Up The Bracket, which remains The Libertines’ finest half-hour. Marrying urgent, garage-rock guitar riffs with the idiosyncratic lyrical wit of The Kinks and The Jam, the record was delightfully ramshackle and boisterous, the sound of a band giddy on youthful rebellion. Their songs about drinkers, smokers and “good-time girls” gripped the cultural zeitgeist, cigarette in hand, and were full of endlessly quotable lines. Take “Time For Heroes”, on which Doherty observes that there are “few more distressing sights than that / Of an Englishman in a baseball cap”. Twenty years on, it still draws a wry smile of recognition.

The story of Up The Bracket began half a decade before its release. In the mid-Nineties, Barât heard about Doherty before he met him. While he was a drama student at Brunel University, he lived in student halls in Richmond and became close friends with Doherty’s sister Amy-Jo. “She kept saying how much he admired me and couldn’t wait to meet me,” recalls Barât. “I was expecting this little introvert, I didn’t expect him to be six foot three! I met this really enormous, towering, argumentative kid. We ended up bickering and sniping at each other, which obviously became a lifelong, beautiful friendship.” Their friendship, and their rivalry, was sealed at that first meeting when Barât said he had to go to an audition. “Pete said, ‘I’ll come with you’, then he auditioned and got the f***ing part!” says Barât with a laugh. “Then he announced that he didn’t go to the university, and everyone was roundly disappointed. Except me.”

For his part, Doherty quickly identified Barât as a potential bandmate. “When my sister first told me about him I thought ‘that’s gonna be the guy that is going to play the guitar for me, but obviously it didn’t quite work out like that,” Doherty says in a new podcast documentary about the making of the album. “Years later when we started trying to write songs, he explained very politely that I wasn’t going to be the lead singer, if anyone was going to sing, we were both gonna do it, so I’d have to learn guitar.”

After Doherty moved to London in 1997 to study English at Queen Mary University, the pair became inseparable. Barât credits his friend with encouraging him to take the dream of forming a band together seriously. “I was a bit f***ing rough and ready back then,” says Barât. “Mental illness, fresh off the estates. He sort of romanticised that in me, and made me feel like it was a good thing. I was such a wastrel with doing bad things to my body in terms of consumption that I think he thought I was too wild for him for a while, but he persisted.” The pair venerated bands like The Smiths, The Stone Roses and The Velvet Underground, and soon they’d both dropped out of their university courses to concentrate on writing their own myths as The Libertines. “We called it ‘throwing ourselves into eternity’, in our sixth form poet way,” says Barât. “But we actually did what a lot of sixth form poets don’t do, and followed through. I wouldn’t say we made a deal with the devil, it was more like a deal with God, or a deal with the universe. We really did throw it all out on a limb, and it actually f***ing came true.”

Sometimes though, even the universe needs a bit of encouragement. The earliest incarnation of The Libertines was a debauched troupe best known for playing hundreds of shows across London anywhere people would have them. “We played a nursing home once, and someone died during ‘Music When The Lights Go Out’,” remembers Barât. “I thought that was an appropriate song to go out on. We’d go around on public transport with our amps to do gigs, singing about love’s vicissitudes and romantic things that no one else thought were very romantic.”

After four years of relentless gigging, the band fell apart. The rhythm section of bassist John Hassall and drummer Paul “Mr Razzcocks” Dufour left, but in July 2001 Doherty and Barât were given a shot of ambition by the release of The Strokes’ debut album Is This It. “When The Strokes happened, we were a bit like, ‘We’ve got those jackets, and we’ve got a lot of anger too to fuel the driving downstrokes [of the music]’.”

The band’s then manager Banny Poostchi came up with a plan to get The Libertines signed, with The Strokes’ British label Rough Trade at the top of the wish list. “By that point, I’d become a bit more strategic and business-minded,” Barât says. “Pete was basically happy to go with anyone who had a four-track in their basement and said they’d put our record out.” Poostchi had devised plan A, which was, among other things, to get the band signed to a label who could do something with them properly. “Instead of signing away the rights to some tinpot f***er in the pub,” Barât explains.

Key to this plan was attracting the attention of an A&R man, and before long Poostchi and the band had convinced Rough Trade’s James Endeacott to see them play at east London venue Rhythm Factory. The band knew he’d want to witness a scene, so they gave him one. “I went round all the performers from the acoustic and open mic nights, and I got everyone who seemed a bit weird and interesting to come to this gig,” remembers Barât. “I said, ‘Guys, you have to pretend that there’s a f***ing scene here and you’re absolutely mad for it.’ John, our exiled bass player, was in the crowd right in the front pogoing like a nutter. We were faking it until we made it, but it was still kind of real. Everyone must have felt the madness and the magic of it, it’s just ironic that it came from a blag.”

Endeacott was convinced, and after further demos were recorded The Libertines signed to Rough Trade on 21 December 2001. Hassall returned as bassist, joining new drummer Gary Powell. The following year, the band were despatched to London’s RAK Studios, near Regent’s Park, to deliver on the promise they’d dreamt up.

By the time Up The Bracket was released, The Libertines had been hyped to the rafters. Not everyone was buying it. A week before the album came out, The Independent’s Steve Jelbert caught the band supporting Supergrass at Rock City in Nottingham. “This twentysomething punk quartet have something going for them, although it’s concealed by their tentative playing and permanently out-of-tune guitars,” he wrote. “Their well-meaning attempts to provide the capital’s riposte to The Strokes are repeatedly foiled by their sloppiness. It takes a lot of work to sound that simple.”

After the band appeared on the cover of NME after just one single and were touted as the saviours of British rock’n’roll, it felt anticlimactic when Up The Bracket entered the charts at number 35. “We didn’t understand the long game,” says Barât. “Why would we? We were precocious neophytes on the scene. The album went in at f***ing 35 or something, and then it was out of the charts. We didn’t really understand that we were building something special. If it had gone in at No 1 we would probably have been flash in the pans.”

Instead, Up The Bracket’s cache has only grown as time has gone by. Pitchfork, whose initial review suggested the album was “calculated” and “derivative”, went on to name the record among the greatest of its decade. Uncut, Rolling Stone and NME all did likewise. This year, the band have been celebrating its anniversary with a string of shows in venues much grander than they commanded when the album was first released. “The fact that young people are still down the front is f***ing meaningful, and something I’m deeply grateful for,” says Barât. “The album is still resonating with people who weren’t born 20 years ago. That’s a beautiful thing.”

Doherty, too, looks back on the band’s first record with evident pride. “We were so desperate to do something,” he told a press conference at north London’s Boogaloo when the band first reunited in 2010. “We couldn’t quite put our finger on what it was but it was something to do with performing songs, and we were kind of falling over ourselves to do it. It all got so messed up. But looking back on it, we actually did produce things that we’re all so proud of.”

Just as remarkable is the fact that the band are still together to see it. Within two years of Up The Bracket’s release, the band collapsed in a flurry of drugs, amateur burglary and prison sentences. They reunited again in 2015, and Doherty and Barât’s mercurial, loving, co-dependent relationship was revived with it. “I think we were bound together by forces greater than those we could control,” says Barât. “The bond that has held us together through very, very adverse circumstances for 25 years has been impossible to break, even when we wanted to. When you’re greater than the sum of your parts, with someone you work with, or love, or have in your life, then that exists outside of you. It doesn’t belong to you. It just is. You can’t get away from it.”

‘Up The Bracket: 20th Anniversary Edition’ will be released on 21 October

UPDATE (21/10/22): This piece has been updated to reflect the fact that Banny Poostchi was the band’s former manager during the release of the band’s debut album Up the Bracket and she signed the band to Rough Trade.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News