Genetic technology used to exterminate disease-carrying animals succeeds in mammals for first time

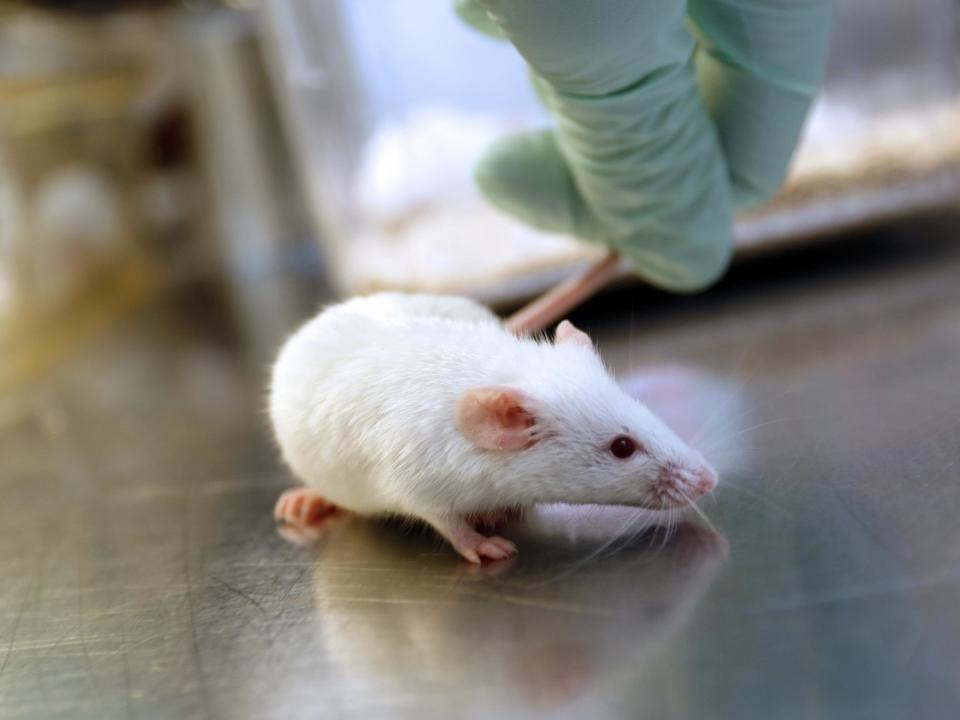

A genetic technology that could be used to to eradicate disease-carrying insects has been succesfully used in mammals for the first time.

Scientists think so-called "gene drives" could one day be used to spread harmful DNA that can wipe out pests or invasive alien species.

The United Nations (UN) recently considered a total ban on the technique after many expressed concerns about unintended and uncontrollable knock-on effects.

So the controversial practice is currently confined to the laboratory, but publishing their findings in the journal Nature, a team of scientists from California have successfully used it to change the colour of white mice to grey.

Led by Professor Kimberly Cooper, the team used Crispr gene editing to add a segment of DNA known as “CopyCat” into a gene controlling fur colour.

This gene drive tilted the scales in favour of the desired gene, meaning when the new mice are born they were more likely to have darker fur.

After two years, around 70 per cent of mice being born had genes for the greyer complexion compared to around half of those in a normal population.

The technique only worked in female mice during the production of eggs and had no effect on the sperm of males.

Excitement about gene drives in the scientific community has largely focused on their potential to tackle deadly diseases like malaria and dengue fever by wiping out biting insects.

This technique has already proven effective in laboratories, where malaria-carrying mosquitoes have been prevented from laying eggs

The scientists behind the new study hoped to lay the groundwork for the creation of mice that could be used in medical research for complicated genetic diseases.

However, some have proposed similar gene drives could be used to control pests, such as rat infestations.

The technique might be more effective than alternative methods such as dangerous pesticides.

“With additional refinements, it should be possible to develop gene-drive technologies to either modify or possibly reduce mammalian populations that are vectors for disease or cause damage to indigenous species,” said Professor Ethan Bier, one of the study’s co-authors.

The work was welcomed by other scientists as a crucial step that confirms gene drives as an effective technique for use in mammals, but they warned that a lot more work needed to be done.

“Considerable optimisation will be required to develop a gene drive system suitable for proposed field applications such as control of invasive rodent populations on islands for conservation purposes,” said Professor Luke Alphey, an expert in genetic pest management at The Pirbright Institute.

While the proposed moratorium by the UN failed to gain support from biotechnology-friendly countries, concerns about mutations and wider environmental impacts still abound.

With the technology still at a fledgling stage, the scientists concluded that both fears and wilder speculation about its applications are likely premature.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News