Glenda Jackson on returning to the stage after 23 years as a Labour MP

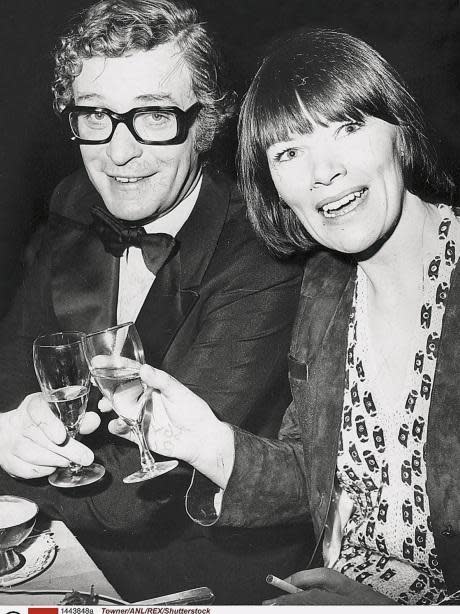

Glenda Jackson should be doing her Christmas shopping, but instead she is explaining to me what it felt like to return to the stage after 23 years as a Labour MP, with an astonishing, cross-gender performance as King Lear at The Old Vic, which won her the Best Actress statuette at this month’s London Evening Standard Theatre Awards.

‘One of the great things about theatre is that you don’t meet people for years, then when you do bump into them, it’s as if you’ve both just walked out of the same room,’ says the 81-year-old. ‘I had worked at The Old Vic before, in The White Devil and Phèdre in the 1980s, and when I walked back in there it was as if I hadn’t been away.’

Jackson had been repeatedly offered acting roles during her time as MP, but none had appealed. ‘I really didn’t miss acting at all, apart from the people,’ she says. ‘Some of the egos that walked up and down those [House of Commons] corridors wouldn’t have been tolerated for 30 seconds in a theatre. But I haven’t even been inside a theatre to watch a performance for 25 years now, which is quite shameful.’ After standing down at the 2015 election, however, she was encouraged to consider Lear by her friend, the Spanish actress Núria Espert, who had played the part in Barcelona.

‘In a curious way it has been mis-sold as if it is exclusively about the eponymous hero,’ she says. ‘But it isn’t. Every single character in it is amazing.’ So when Matthew Warchus courted her for another play at The Old Vic, Lear was her counter offer. Deborah Warner, who pioneered gender-blind casting with her Richard II starring Fiona Shaw in 1995, came on board as director. If the cast, which included Celia Imrie, Jane Horrocks and Rhys Ifans, were in any way daunted by the returning icon, they didn’t show it. ‘Nobody made a big deal about it,’ Jackson says. ‘We were all just engaged in making the play the best it could be.’ However, Jackson mischievously says, when a weekday matinee was added ‘they all thought I was going to die’.

For London theatregoers, of course, it was a very big deal. Jackson, the eldest of four daughters of a Birkenhead builder and a shop assistant, was part of the working-class wave that reshaped post-war British theatre and film. She was a key component of Peter Brook’s radical reinvention of the Royal Shakespeare Company — with the revolutionary Theatre of Cruelty season, including the notorious Marat/Sade and the Vietnam protest play, US — in 1964, just three years after the company was founded. As the 1960s segued into the 1970s, she starred in Women in Love and The Music Lovers for Ken Russell who, as she put it, ‘tore the envelope of British film into tiny little pieces and put it on a different path’.

In the title role of the BBC’s six-part, nine-hour regal drama, Elizabeth R, in 1971, she arguably set the template for all later portrayals of the Virgin Queen, and helped create the idea of the serious, long-form TV drama. ‘Oh please!’ she snorts in derision at this last suggestion. ‘Though you couldn’t do a series like that now, certainly not in-house at the BBC.’ Her main memory of that show is that ‘every time I went to White City for a costume fitting or something, there would be this drama about whether I could park my car in the grounds. There was a sense back then that the office staff and managers were the important people, and what went on in front of the camera, unless it was football, was of lesser importance. I think that has changed.’

In the 1980s, as well as her work at The Old Vic, she did O’Neill on Broadway, reunited with Russell to play the mother of her Women in Love character in his film The Rainbow, and starred in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in Los Angeles under the direction of the play’s author, Edward Albee. ‘I’d be lying if I said that was a meeting of minds or artistic drive,’ she says. ‘He was a terrible director, and I regarded him as essentially misogynistic.’ She was also brilliantly funny on The Morecambe & Wise Show and The Muppet Show.

But in 1992 she gave it all up when she was asked to stand against the sitting Tory MP Geoffrey Finsberg in what was then the constituency of Hampstead and Highgate. What inspired her socialist politics, I ask. ‘Well, my parents were classic floating voters, so a lot of it came from American literature, Sinclair Lewis and so on, and that wonderful idea of government “of the people, for the people, by the people”,’ she says. ‘And also the genuinely transformative political decisions the Labour government brought into being at the end of the war, like the National Health Service.’

When she won her seat, many thought she’d seek a starring role. ‘Lots of journalists said, “Do you want to be leader?”,’ she recalls. ‘And I thought, for God’s sake, I don’t even know what being an MP is. For me the most interesting part was the constituency work.’ She became a junior transport minister but fell out with Tony Blair over Iraq, famously lambasted both Iain Duncan Smith and the late Margaret Thatcher for their social policies, and is a qualified supporter of Jeremy Corbyn. ‘We were contiguous [in our constituencies] and he was marvellous. I could go to him and ask him a question and he would always be helpful. When I decided not to stand again in 2015, I wrote to him and said, my only sorrow is that I can’t nominate you for the leadership. I felt we always had to have a left-wing contender. I would never in a million years have voted for him, but there he is, God love him, he has grown into it.’

She once put herself forward as a candidate for Mayor of London — mainly to ensure that there was a woman on the list — and is a fan of Sadiq Khan. ‘It’s the policies, of course, but also the tone he has struck,’ she says. ‘Whereas Boris was a clown with London as a backdrop, with Sadiq you know London and its people are absolutely to the fore.’ She is, of course, depressed about Brexit and Trump. ‘At a time when I would have thought it was obvious to everyone that the world is moving in a direction where we become more united, there seems to be this fashion for putting up walls and barriers and underlining difference to claim a superiority which is not ours,’ she frowns.

But Jackson, as you may by now have gathered, is not much given to introspection or brooding. Indeed, the spikiness other interviewers have ascribed to her strikes me as mere let’s-get-on-with-it impatience. It’s what makes her acting so electric: she lives absolutely in the moment and suggests that every performance, whether it’s the last night of a play or the 94th take of a film scene, feels in some sense like the first time you’ve done it. She is also splendidly matter-of-fact about everything, from the CBE she was awarded in 1978 (‘I’d only want to be a dame if it was in panto’) to her recent modelling campaign for Burberry.

We discuss the endemic sexism of not just the entertainment industry and Parliament, but society as a whole. Some things have got better — Parliament doesn’t sit as late and MPs can take babies into the chamber, actresses are more likely to call out sexist terminology like ‘love’ or ‘darling’. But at the Evening Standard Theatre Awards, host Phoebe Waller-Bridge devoted much of her brilliant routine to excoriating sexual abuse in the entertainment world. ‘And are we expected to believe this is the only area where it is going on?’ Jackson says. ‘Two women die in this country every week at the hands of their partner.’

She was never sexually harassed herself, but was routinely patronised, both in the theatre and in politics. When she won a scholarship to Rada aged 18, after working in Boots for two years, the principal told her she wouldn’t work much until she was 40. But that, she says, was a valid reflection of the parts available then, and not much has changed. ‘I still find it bemusing that dramatists don’t find women interesting. We are rarely if ever the dramatic engine of whatever is put on the page and then on the stage.’ When she appeared nude in The Music Lovers, tabloids dubbed her ‘the first lady of flesh’, which strikes me as a way of belittling her talent and classical credentials.

‘Oh no,’ she says, ‘what tarnished one’s classical credentials was working in Hollywood. There was still that big line between what was serious, which was theatre, and what was not, which was cinema. And now, of course, what is serious is television.’ Her first big American movie was A Touch of Class opposite George Segal in 1973, for which she won her second Oscar (the first was for Women in Love) and her second Evening Standard Film Award (the first was for her reprised role of Elizabeth I in Mary, Queen of Scots). She talks warmly of Segal’s professionalism and passion for acting, and is an avid devotee of his current sitcom, The Goldbergs. Turns out she is quite a box-set devotee. ‘I could probably recite The Wire and The West Wing. I watch The Big Bang Theory and Modern Family and a marvellous programme I came across by accident, called Black-ish. Bloody marvellous!’ This seems to be about the only thing she does for fun, apart from smoking (she cut down to 10 Dunhill a day for Lear).

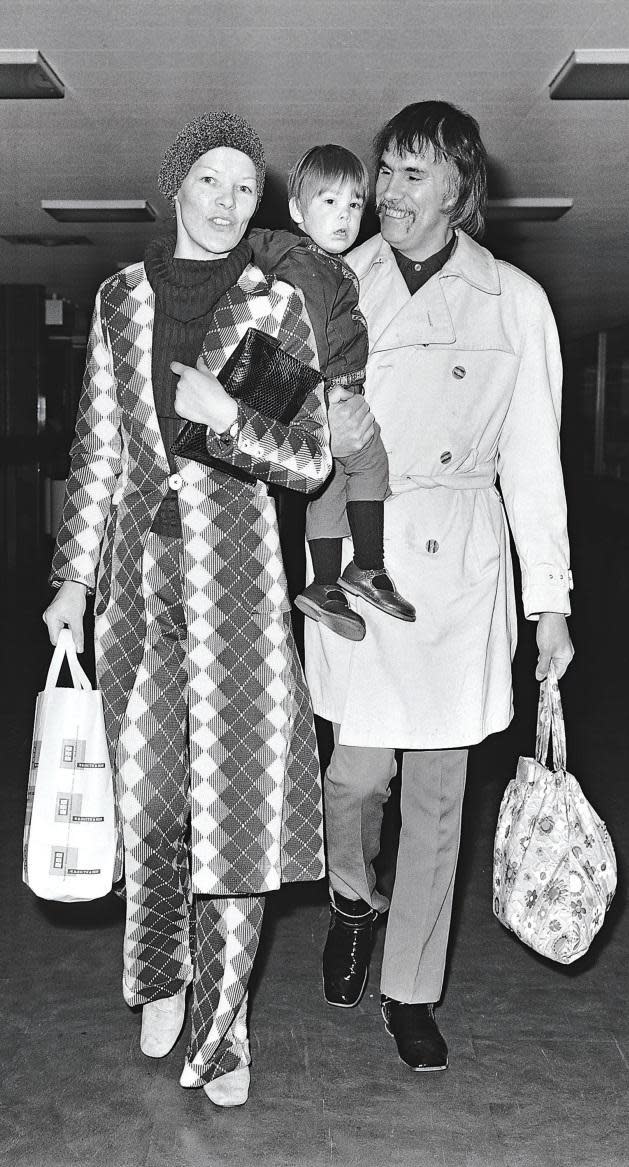

Back in the 1990s, Jackson gave an interview in which she said she had never been in a relationship that was not abusive. ‘Well, that’s true,’ she says. ‘There is always a point where a man will throw something at you, physically, vocally — not in my case to the point of murdering you. There are no social or financial barriers to domestic abuse. What I think has changed but needs to change even more is the idea that what goes on behind your front door stays behind your front door.’ In that same interview, she also said that her relationship with theatre director and art dealer, Roy Hodges, to whom she was married from 1958 to 1976, ended because she had an affair with a lighting technician — with whom she then went on to live for five years. She has apparently been single since then. ‘You get set in your ways,’ she shrugs.

Today she lives in a basement flat in Blackheath, while her son, the journalist Dan Hodges — she was five months pregnant with him when she wrapped Women in Love — his wife and their 11-year-old son live in the house above. It’s their Christmas presents she should be buying. ‘Christmas Eve and Christmas Day are pretty much family based,’ she says, ‘but we are not up at two o’clock in the morning now my grandson is older.’ Is she a doting grandmother? ‘No, we fight all the time. I am a stern disciplinarian, which is just water off a duck’s back as far as he is concerned.’

Anyway, the present-shopping will have to wait — ‘I always do it at the last minute’ — because Jackson has a meeting. Next year she is to appear in Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women on Broadway, a project that plays to her lack of vanity and brings out her impatience. ‘It’s a very interesting piece, and it’s very unusual to come across a play where all the parts are women,’ she says. ‘The part I’m playing is based on his adoptive mother, and they clearly didn’t get on. He says in the foreword that he never met anybody who liked her. We start rehearsals in January. I just wish we were starting now.’

Yahoo News

Yahoo News