Glitches dent German enthusiasm for Covid contact-tracing app

As Britain prepares to unveil its own coronavirus contact-tracing app, Germany is drawing less than enthusiastic first conclusions about the effectiveness of battling the pandemic with smartphones.

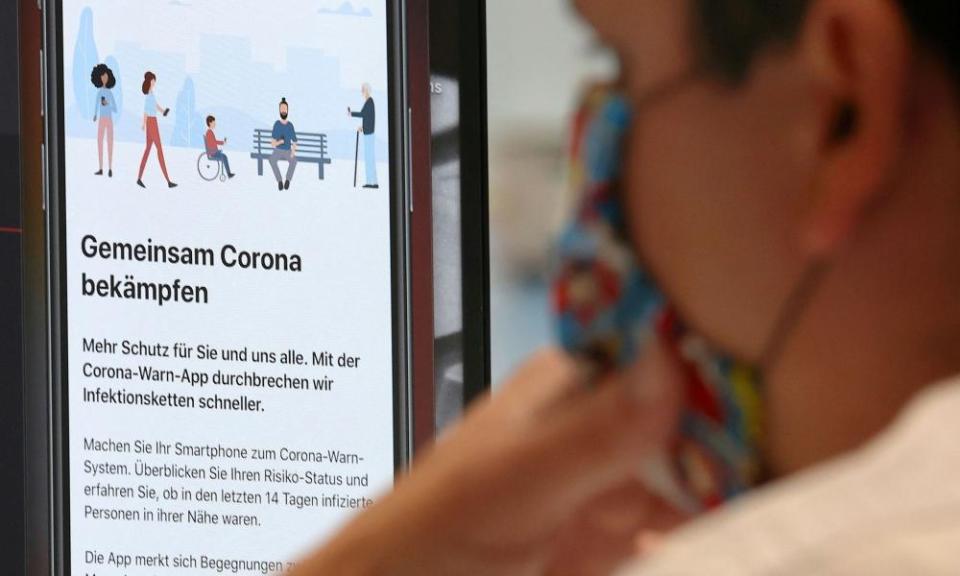

A hundred days after its launch, German authorities conceded that IT glitches and poor communication channels with laboratories make the country’s Corona-Warn-App “one more tool of many” rather than a Covid-19 cure-all.

The German app, which drew praise from as far as Westminster after it was launched on 16 July, had by the start of this week been downloaded 18.4m times in Germany and 400,000 times abroad – more than similar apps in all other EU member states combined.

About 1.2m test results have been conveyed to patients via their smartphones.

Twenty-two per cent of a German population of approximately 83 million have downloaded the app on their phones, not far off the 33% uptake that the government’s panel of expert advisers announced as a minimum requirement for the contact-tracing technology to do its job.

Earlier in the summer, many health officials had targeted a 60% pick-up rate for the app, based on an Oxford University study released in April, though Telekom’s chief officer, Timotheus Höttges, said on Wednesday that latest studies showed an uptake of 15% to be enough to lower coronavirus’s mortality and infection rate.

The number of people who actively use the app is likely to be lower, however: some users will have deleted the app again, while others have switched off the Bluetooth signal needed for the technology to work.

Using download figures from Apple’s App Store and Google Play, Telekom says it believes the coronavirus app to have 15 million active users.

The development phase of the German app was accompanied by an intense discussion around data privacy that resulted in the government moving to a decentralised model, which uses Bluetooth technology to anonymously log the proximity of any other smartphones with the app installed.

As a result, Germany’s central disease control agency, the Robert Koch Institute, is short of data to tell how effective the app has been. For example, there are no official figures on how many people have been warned they were exposed to someone with the virus.

Accredited Laboratories in Medicine (ALM), the largest association representing laboratories in Germany working on the tests, cites a number of 3-6% of tests it has analysed that were explicitly taken because people had been warned by the app.

The app does not automatically send warnings to contacts if users have tested positive but requires the user to press a button to do so. On Wednesday the health minister, Jens Spahn, said almost 5,000 people had used the app to warn their contacts – only half of those who had received a positive test result through the app, and only about 10% of the overall new infections in Germany since the launch.

As well as only working on newer smartphone operating systems, experts found the app’s contact tracing via Bluetooth to work unreliably on buses, trains and subways, where the risk of an infection is higher than in open air. Other users have complained of error messages that would not go away after un- and reinstalling the app.

For the app to work smoothly, laboratories should be able to feed their test results directly into the app. But by Monday 20% of German labs who can carry out PCR tests were still unable to do so, because their software was incompatible with the app’s digital infrastructure, developed by Telekom and the tech giant SAP.

“We invested a lot of effort into addressing concerns around data privacy, but less into working out how test results find their way on to your smartphone”, said Axel Oppold-Soda, an ALM spokesperson.

Oppold-Soda said he still believed the coronavirus app could make a “very important contribution towards the contact-tracing effort”. But views on the effectiveness of the app among the public at large have become less optimistic.

A recent study by Munich’s Technical University found that 51% of those questioned did not believe the app would change the development of the pandemic. In June, before launch, only 41% had expressed the same opinion.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News