The Government must take renewed action on the NHS crisis

That the NHS is under increasing pressure will not come as news to anybody. Nevertheless, with every fresh statistical analysis, the challenges facing the organisation become ever clearer – and more worrying.

A survey by the BBC is the latest indicator of the downturn in the NHS’s performance, with targets for cancer treatment, A&E services and even pre-planned operations all being missed as a matter of course. In England especially, the decline in meeting key targets has been startling in the last five years: in 2012-13 they were met, at the national level, 86 per cent of time; in 2016-17 they were not met at all. Twelve trusts missed all three targets every month.

At the most basic level, the problems are obvious: there is an increased demand for services and not enough money to fund it. NHS England’s director of acute care, Professor Keith Willett, noted in response to the BBC’s findings that “it will be difficult for the NHS to continue on the trajectory that we want to set”, unless improved financing is forthcoming from government. In an atmosphere of continued austerity, even easing the public sector pay cap is presented as a stretch, the chances of the NHS receiving the kind of injection it really needs are therefore limited.

Plainly the burden on services has been growing for some time, an inevitable consequence of Britain’s ageing population (and of the fallout from the financial crash). The particular pressure on social care and mental health services has had a knock-on effect on emergency departments, which are left picking up cases that ought to be dealt with by properly resourced, specialist units.

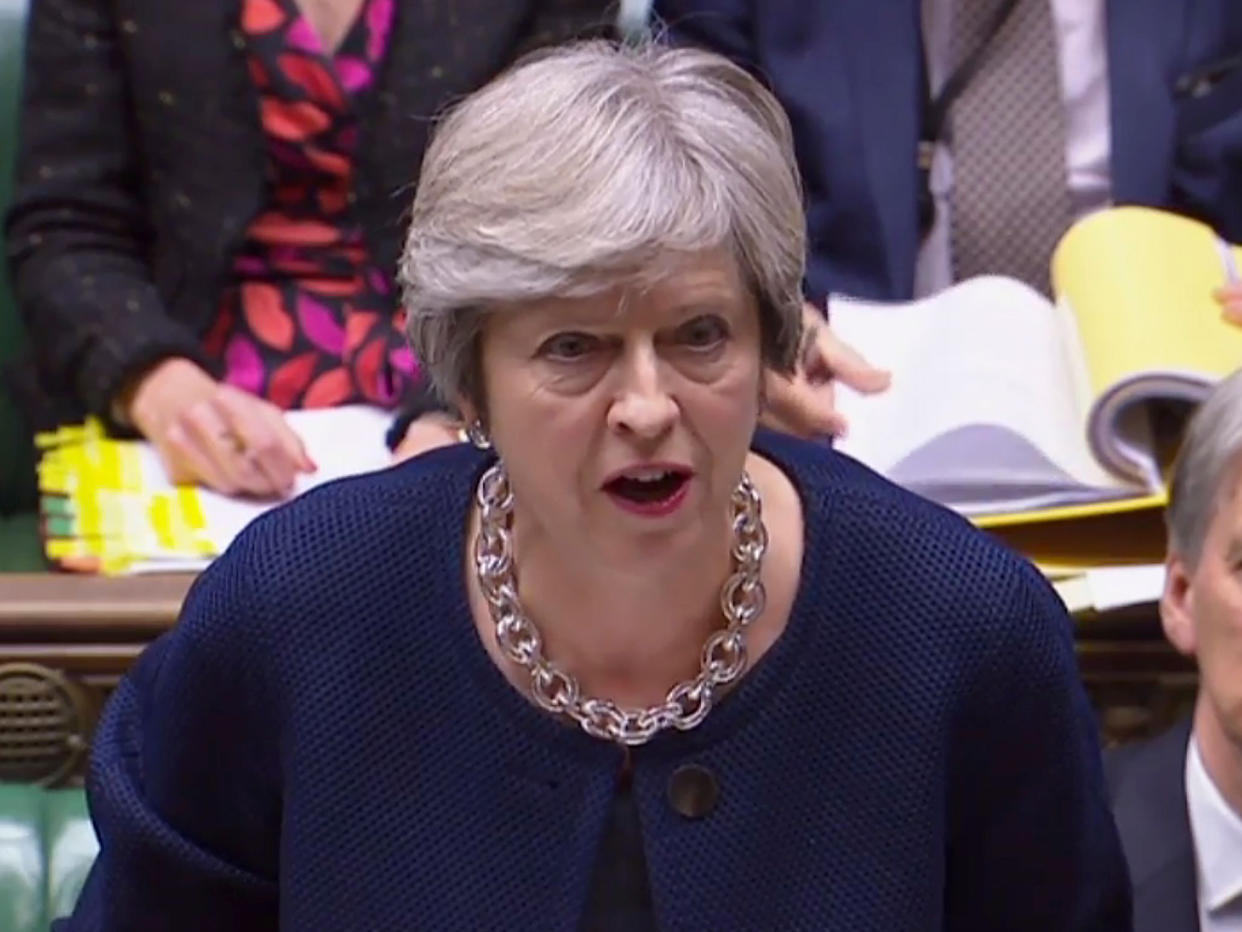

The Government has set out ambitious plans to tackle the lacuna in mental health care, promising in July to create 21,000 new posts in order to be in a position to treat an extra one million patients by 2021. Even in this arena, however, there remain question marks. The Royal College of Nursing has queried whether the £1.3bn on offer is sufficient to realise Jeremy Hunt’s hopes for a transformed service. What’s more, the other burning issue – of improved social care for the elderly – remains largely neglected. Indeed, after the debacle of Theresa May’s subsequently recanted proposals for what became known as a “dementia tax”, it is hardly difficult to see why there is reluctance to reopen the debate, beyond the more marginal aspects.

Ultimately, it is a question that will require an answer, since the present state of social care is signally inadequate for the country’s requirements. Labour has raised the prospect of consultation on a range of funding options but it is becoming difficult to conclude that the present shortfall can – especially in the long run – be met simply from increases in income tax or government borrowing.

For doctors and nurses on the front line, patience is in many cases wearing thin. Instances of emigration and early retirement are commonplace, as long hours, unyielding paperwork and – in some cases – low pay take their toll. In 2016, 59 per cent reported working unpaid overtime each week. For all the talk about increasing the overall number of medical professionals in the NHS, the truth is there are already up to 40,000 nursing posts unfilled. GP practices regularly struggle to retain doctors.

For almost 70 years the NHS has been both a remarkable testament to Britain’s post-war political and social settlement, and the envy of many other nations. The ideals that lie at its heart, that there should a national system of free healthcare, meeting the needs of all on the basis of clinical need rather than ability to pay, remain as precious today as they were in 1948. And for the most part, the service which the NHS provides to patients is high-class.

It is precisely for these reasons that the Government must keep the NHS at the top of its list of policy priorities – Brexit or no Brexit. Presuming that EU withdrawal is not reversed it will be more crucial than ever that Britain’s key sectors not only function effectively to meet the needs of people living in the UK, but also attract talent (from home and abroad) and promote innovation. A successful, properly funded NHS is more than simply a means to ensuring that Britons remain in good health; it is a byword for the condition of the nation.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News