Grassroots Football in Crisis: Our report on the shameful state of facilities and how football helps kids avoid a life of crime

There has never been so much money at the top of English football, nor such a yawning gap between the game’s haves and have-nots.

The cut-throat battle for the Premier League TV rights over the years has seen a huge rise in the bidding — with a windfall of £4.4billion for 2019-22.

Clubs are reaping the rewards. The deal has left the majority in unprecedented positions of financial strength.

Last year, the English top flight became the first football league to pay its players an average of more than £50,000 a week, dwarfing its European rivals. In Spain’s La Liga, players are paid an average of £32,000 per week.

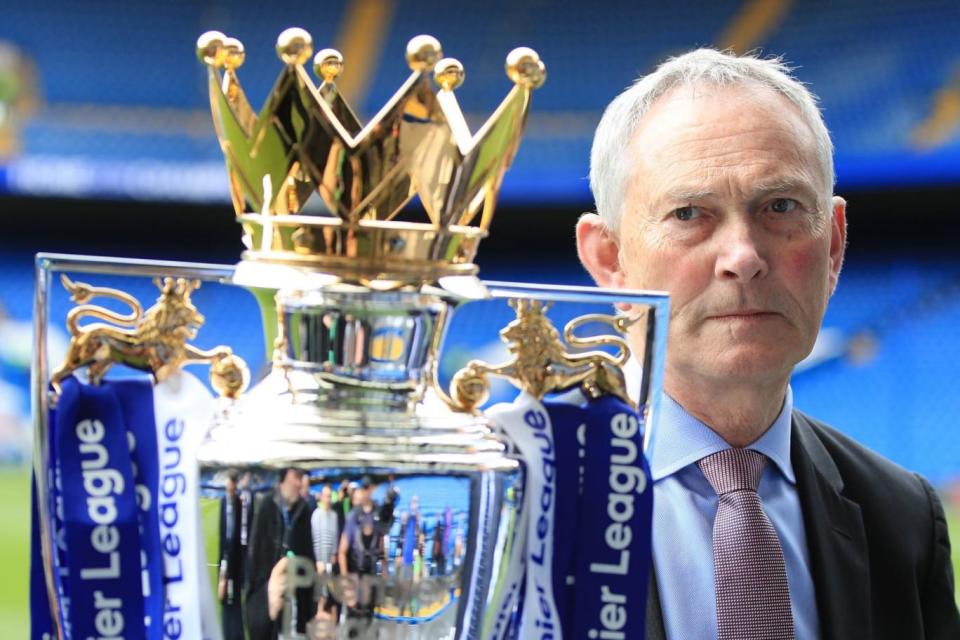

Outgoing Premier League chief executive Richard Scudamore (below) was casually handed a £5million golden handshake by clubs last month, offering a clear sign of the excess at the top of the game and angering those who believe the money could have been better spent on more progressive causes.

Forefront among them is grassroots football. Far away from the gilded, professional environment of the Premier League, many grassroots clubs are struggling to stay afloat.

The Football Foundation — the UK’s largest sports charity, which channels money from the Football Association, the Premier League and the government into grassroots sport — has described the state of facilities across the country as “in a shameful state”.

It’s only fair to say that the top of the sport does a lot to help. Between them, the Premier League, the FA and the government invest £72m per year into the Foundation, with £24m coming from the top-flight.

Since the Foundation’s formation in 2000, the Premier League has invested £302m, the FA £299m and the government £273m — a total of £874m. The Foundation continues to work tirelessly to build artificial pitches and improve grass pitches and other community facilities.

In London alone, £235m has been spent on more than 3,500 community projects since 2000, including 113 artificial grass pitches, 400 natural grass pitches and 71 changing rooms.

While it is sobering to think where the grassroots game would be without such a sustained commitment, the current arrangement is still not enough.

Figures from Sport England’s Active Lives survey show that 94,000 football matches were cancelled nationwide last season, while only one in three pitches was deemed “adequate” by the FA.

For a country in which nearly one in five of us — an estimated 8.2m people — play some form of the game, more needs to be done.

The FA recognised the shortfall by pledging to give the Foundation the proceeds from the £600m sale of Wembley Stadium to Fulham and Jacksonville Jaguars owner Shahid Khan earlier this year.

The collapse of Khan’s proposal eight weeks ago leaves English football’s governing body in desperate need of finding another means of investment.

England’s success at youth level during the golden summer of 2017 and the senior team’s run to the World Cup semi-final were no coincidence, rather the result of considered, long-term strategy. But English football risks failing the next generation of hungry, talented footballers.

For London, a city which has endured one of its worst years of street violence, there are also wide-reaching social implications.

The Premier League’s success has helped ensure football has never been so popular and it is providing deprived young people with an escape and a means to improve their lives.

There are clear health implications for body and mind too.

For this investigation, Standard Sport has talked to the grassroots volunteers who are the first to work with the Premier League stars of tomorrow and the community leaders saving young people from a life of crime in London’s gangs.

We sought the Londoners for whom football has been a salvation, including a Premier League star, and talked to health professionals about how sport is one of the most effective means of managing mental illness.

Finally, we asked the FA, the Premier League and its seven London teams if they can do more to help and examined where new investment could come from.

Can't see our Grassroots Football in Crisis special report? Click here to access our desktop version.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News