On the ground in Yemen: ‘A place of wonder overshadowed by conflict’

Yemen, and very dear Yemeni friends, hold a special place in my heart. But every visit is a bittersweet experience; even memories of the nicest afternoon can end up enveloped in sadness.

During a 2019 trip, I was waiting for permission from the Houthi rebels to travel to the north, and got stuck in a desert town called Marib for a few days. I was tired from nonstop travel, the heat, eating badly, and trying to get any decent reporting done. Nothing happens very quickly in Yemen, if it happens at all.

A good friend has relatives displaced by the war living in the town, and they invited me for lunch one day. It was a wonderful afternoon. The mum, Faiza, must have been cooking since dawn: she made a dozen dishes, including saltah, my favourite stew, and a special honey cake called bint al-sahn I hadn’t tried before.

We talked about politics and the war, but we also played games and had some fun with the kids. Their youngest child was a gorgeous two-month-old called Khadijah. Spending time with a normal family, doing normal things, and in particular playing with a fat, healthy, bonny baby, was so restorative. I remember thinking at the time: I wish I could put this stuff into stories, the fact that not everything is doom and gloom. That life goes on.

It felt devastating to receive a message from a member of the family three months later to tell me that Khadijah had got sick with a fever and died. Her parents had taken her to the local hospital, but there was no doctor available to help.

I think about her little life a lot. For Yemenis, the war is always there; they don’t have the luxury of ignoring it for long. If people are willing to share difficult or painful experiences with me – as Khadijah’s family are for this story – I have a duty to keep going too. Reporting what people in the country have to say, and what they are going through, is a privilege I take very seriously.

The commitment from my editors is also impressive. They are willing to invest in this expensive and time-consuming work because they understand it’s vital. Not many newspapers have the resources to do that.

One of the reasons Yemen’s conflict has gone under the radar for so long, I think, is because the borders and airspace are sealed: hardly any refugees come out, although 3 million people are displaced inside. If Yemenis were making their way to the shores of Greece and Italy, telling their own stories without fear of being targeted by the warring parties at home, the political pressure on western governments to stop selling arms would be much greater.

The Saudi-led coalition blockade is also the biggest obstacle to working in Yemen; it’s very difficult to get in. The coalition refuses journalist visas far more often than it grants them.

Yemenia airlines, the state carrier, only has six planes in its whole fleet, so seats are like gold dust, and flights often get cancelled without warning on coalition orders. The other option, if you can convince the border officials, is to drive from south Oman. From there to Aden, Yemen’s temporary capital, is approximately three days’ journey.

Most conflicts that have been going on for more than a few years get extremely complicated, and Yemen’s is no exception. There are forces loyal to the exiled Yemeni government, and the Houthi rebels, and a movement formed in 2017 which wants South Yemen to be independent again, so effectively it’s three wars in one, plus al-Qaida and Islamic State cells in the desert.

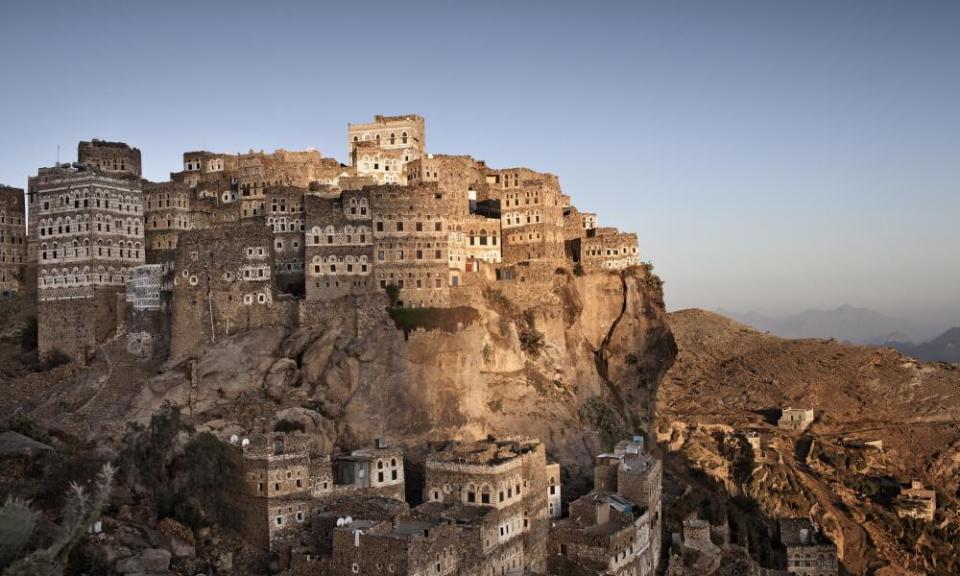

The fighting and the devastating human toll of the war also overshadow the fact that the country remains a breathtakingly beautiful place.

Some parts of Yemen couldn’t be more different from the regional stereotype of endless sand. When you’re approaching the highlands of the north it feels like entering a fairytale kingdom: banks of cloud tumble down green farming terraces; gingerbread-like castles dating back to medieval times cling to the mountainside.

The best coffee in the world comes from the Yemeni mountains, while prayers and music ring out from ancient Sufi-built mosques. It’s a place of deep, storied history and culture and unique natural phenomena: the Socotra island archipelago is known as the Galápagos of the Indian Ocean.

Of course it would be better for Yemen to be celebrated for its wonders rather than pitied for its bloodshed. Unfortunately, however, even with the new diplomatic push from Joe Biden’s administration, the war won’t be ending any time soon. The fighting between the Houthis and Yemeni government forces got steadily worse throughout 2020 and the beginning of this year.

Marib, where Khadijah’s family live, used to be seen as a haven for people from other parts of the country fleeing violence. But the Houthis have launched a major offensive in the area, and 2 million people are at risk of having to move again, in what could be the worst mass displacement of the war. This time it’s not so clear where so many people can go.

The humanitarian situation is going to get dramatically worse in the next few months. There’s a huge aid funding shortfall this year, and half of the country is already starving. Yemen is also looking at a second wave of coronavirus, although it’s impossible to tell how much impact the pandemic is having because testing facilities are almost nonexistent.

All of these things make covering Yemen at times a draining and emotional experience. But feeling that my work can help make a difference is a powerful motivation.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News