The Groundhogs’ Tony McPhee will remain a hero for the musically adventurous

The comic strip cover of the 1972 album Who Will Save the World? The Mighty Groundhogs depicts the trio as a band of superheroes – Powerful Pustelnik, Quick Cruickshank and Marvellous McPhee – battling villains determined to overpopulate and pollute the world. But there’s a sting in the tale. The superheroes are a dismal failure. Limping away from their victorious enemies, they transform into their “secret identities”: a “curiously contrived blues and rock group whose name coincidentally happens to be the Groundhogs”. The final panel thunders: “The rock group Groundhogs might even accomplish more with music than the superhero Groundhogs ever will”, which, given that the superhero Groundhogs have just achieved absolutely nothing, is not saying much.

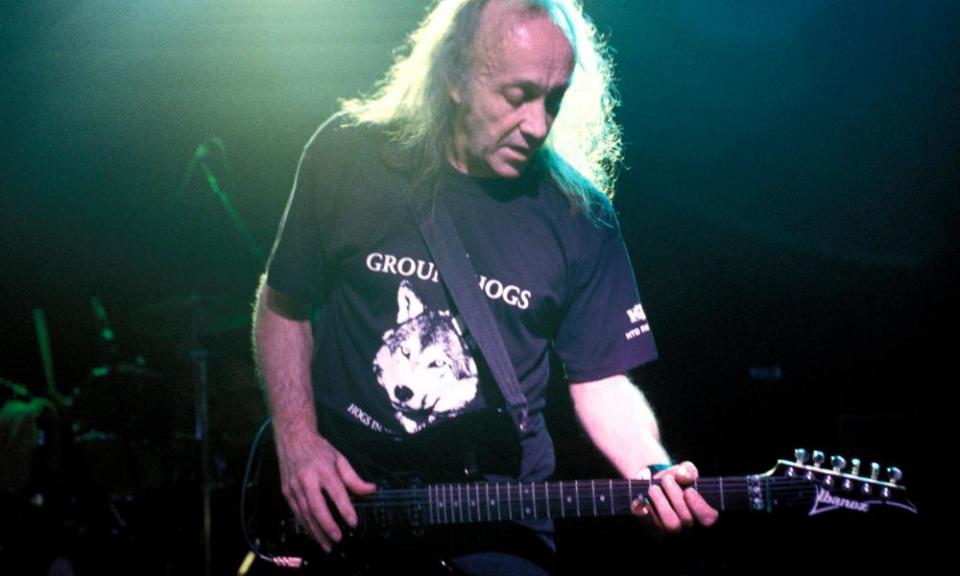

The illustration was the work of celebrated Marvel and DC artist Neal Adams, but, with its self-deprecation and understatement, it seems very Tony McPhee, the Groundhogs’ singer and guitarist, who died on Tuesday. As guitar heroes of the late 60s and early 70s went – and even the most cursory listen to his extraordinarily inventive and powerful playing on Who Will Save the World or its predecessors, Split and Thank Christ for the Bomb, demonstrates how “guitar hero” was a soubriquet McPhee fully deserved – he was remarkably unassuming. Dressed down and resolutely unglamorous, he claimed his second wife had left him because he was “boring”.

He never seemed fond of the spotlight. The Groundhogs sold a lot of records in the early 70s: after supporting the Rolling Stones on their 1971 UK tour, they found themselves subsequently filling the same venues as headliners. But to the end of his life, McPhee maintained that the highlight of his career wasn’t their run of Top 10 albums but the time he had spent in the 60s as a sideman with John Lee Hooker. He downplayed his shift from playing straight blues to something more experimental as merely a matter of pragmatism – “to keep the Groundhogs working and recording” when the late 60s blues boom began to wane – which didn’t really account for how far out he was prepared to take his music. Plenty of blues players diverted into heavier territory, but few released a 19-minute conceptual synthesiser piece bemoaning the cruelty of foxhunting and “the English upper classes … [who] I loathe”.

The Groundhogs proved influential on a bewildering variety of younger musicians – everyone from the Fall to Underworld to Queens of the Stone Age – but McPhee tended to underplay that, too. “It’s gratifying that people regard the music as still being relevant,” he told an interviewer in 2019, and that was about as far as basking in his serried influence went.

Perhaps his phlegmatic attitude to success and influence was a result of the Groundhogs’ classically hard 60s apprenticeship, during which he earned the nickname TS: the initials stood for Tough Shit.

There were a couple of flop singles (their cover of the Sly Stone-penned I’ll Never Fall in Love Again on star producer Shel Talmy’s short-lived label Planet attempted to position them as purveyors of horn-assisted mod-friendly R&B), a stint acting as supporting musicians for future Bad Company bassist Boz Burrell, and an endless round of club gigs, at which they often performed as a backing band for visiting blues legends: not just John Lee Hooker, but Little Walter, Jimmy Reed and Memphis Slim. The latter was a role in which the Groundhogs excelled: the album they made with Hooker in 1964, … And Seven Nights, was raw and powerful. A clip of them performing Boom Boom live on television the same year shows a band eminently capable of keeping up with Hooker’s fabled spontaneity and idiosyncrasies.

But even the lavish praise of their heroes – Hooker called them “the best band in England” – couldn’t sustain them. They broke up in 1966, and McPhee briefly dabbled in pop-psychedelia with Herbal Mixture. Their second single, Machines, is actually pretty good, and highly prized by psych collectors, but you could somehow tell McPhee’s heart wasn’t in it: a man who had found his calling the moment he encountered Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated at the Marquee club, he was not a fan of pop music, regardless of whether it came dressed in a kaftan. When the success of Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac suggested the world was coming around to his way of thinking, the Groundhogs reformed.

Their debut album, Scratching the Surface, was tight but rough-edged electric blues: Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson covers; a lot of harmonica. Things got heavier and weirder on 1969’s tellingly titled Blues Obituary – the songs a little longer, the tempos either sludgier or more manic. McPhee’s fraught, expressive slide guitar soloing on Light Was the Day a sign of where things were headed. Thank Christ For the Bomb (1970) and Split (1971) were the albums on which the Groundhogs colonised a musical area that was uniquely their own, or at least existed somewhere in between many of the era’s prevalent rock trends.

With their songs inspired by grim drug experiences, alienation and the mordant humour of Thank Christ for the Bomb’s title track, they were very much of their era – the grimy hangover at the end of the 60s party – but they were too expansive to be lumped in with the bludgeoning proto-metal of Black Sabbath and Uriah Heep. There was a hint of progressive rock about the song’s contrasts and dynamic shifts, and a hint of the concept album about Split, which turned the “month of terror and confusion” that followed McPhee’s brush with LSD-laced marijuana into a four-part epic, but the Groundhogs didn’t keep comfortable company with Yes or King Crimson either. They were too raw and chaotic (their drummer Ken Pustelnik, McPhee explained, “just wallops everything in sight and sometimes I lose him completely … and Pete [Cruikshank, bassist] doesn’t help either, because he’s all over the place. So when we fall apart, we really fall apart”) and too defiantly rooted in the blues.

McPhee had developed a fantastic, mush-mouthed vocal style that leaned towards blues without obviously imitating his American idols; he sounded dazed and pleading rather than struttingly macho. They occasionally veered towards the gritty, urban, post-hippy world of Ladbroke Grove’s squat lands – there was an undertone of class warfare to McPhee’s lyrics, and the back-to-the-land agrarianism hymned on Thank Christ for the Bomb’s Garden involves scavenging “clothes from heaps, my food from bins” and “tramps for all my friends” – but he was too pyrotechnically skilled a guitarist to fit with the thrilling ur-punk din of Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies.

He was also stubborn (clearly he hadn’t been nicknamed Tough Shit for nothing), happy to follow his muse into waters that alienated the Groundhogs’ growing following. Fans enticed by the furious power of Split’s most famous track, Cherry Red, seemed baffled by 1972’s Who Will Save the World, with its jazzy leanings and Mellotron synthesiser. But their confusion only appeared to spur McPhee on. Its successor, Hogwash, shifted even further away from the albums that had made them famous: more complex songs, more abstraction, more electronics, including an early guitar synthesiser. McPhee’s 1973 solo album, The Two Sides of Tony (TS) McPhee, had an A side of acoustic blues songs and a B side consisting entirely of The Hunt, an extraordinary 19-minute track performed entirely on an ARP 2600 synthesiser and a primitive Rhythm Ace drum machine, McPhee’s voice sharing space with passages of spoken word and moments that sound like musique concrète or Suicide.

It was quite a way to bring the Groundhogs’ moment in the commercial sun to a crashing conclusion. The more straightforward Solid, from 1974, failed to make the Top 30 and spent only one week on the charts. They broke up shortly afterwards.

When they returned two years later, with McPhee the only member remaining from their early 70s power-trio lineup, it was with a noticeably different, softer sound. Crosscut Saw and Black Diamond have a lot to commend them and McPhee’s playing still has a tendency to leap aggressively out of the speakers, but their radio-friendly sheen is a world away from Split. Thereafter, McPhee’s career played out between largely acoustic solo work and new versions of the Groundhogs; occasional new releases were swamped by live albums and archive collections.

That he was never short of younger musicians to work with says something about the extent of the Groundhogs’ influence. The sound of McPhee wrenching awesome swoops and screams out of his guitar on Garden, or of the jagged, impassioned soloing on Split Part 4, had a once-heard-never-forgotten quality: many of his fans became musicians themselves.

Mark E Smith may well have appreciated the unbending, Tough Shit aspect of McPhee’s approach as much as the music: when the Fall finally covered the Groundhogs’ Junk Man, on 1994’s Middle Class Revolt, it was hard to work out whether the songwriting credit to “Tony McFree” was a misprint or a sly tribute.

After the dust settled, it turned out the Damned and Joy Division were fans. Peter Hook proclaimed them “absolutely revolutionary”. “They were the first band I ever saw live and they’ve been a constant in my life ever since,” said Underworld’s Karl Hyde, who subsequently attempted to collaborate with McPhee. The results have never been released.

They made their mark on grunge, too. Sub Pop’s producer of choice, Jack Endino, apparently played the Groundhogs to any artist he worked with, a list that included Nirvana, Soundgarden and Mudhoney. Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus said his all-time favourite album was Thank Christ for the Bomb. Queens of the Stone Age covered Eccentric Man from the same album. Most recently, Alex Turner claimed the Groundhogs were an influence on Arctic Monkeys’ AM.

A 2009 stroke severely curtailed McPhee’s career. It left him with dyspraxia, unable to sing, although he still performed live. In 2014, the year he announced his retirement, he was to be found on stage with Current 93, guesting on their cover of 1974’s Sad-Go-Round: a man who had kicked off his career with John Lee Hooker performing half a century later with one of the leading lights of the post-Throbbing Gristle esoteric underground. Unassuming as he was, his music had been on quite a journey, one that’s unlikely to end with his death.

“I was never fashionable,” he told an interviewer not long ago, but that meant that his music ultimately transcended fashion: as the era that spawned them fades into history, Thank Christ for the Bomb, Split and the rest are albums you suspect left-field artists will always be drawn to. That final panel of the Who Will Save The World? The Mighty Groundhogs cartoon turned out to be absolutely right.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News