'The ground's been ripped from under them': mental health fears for the children of the pandemic

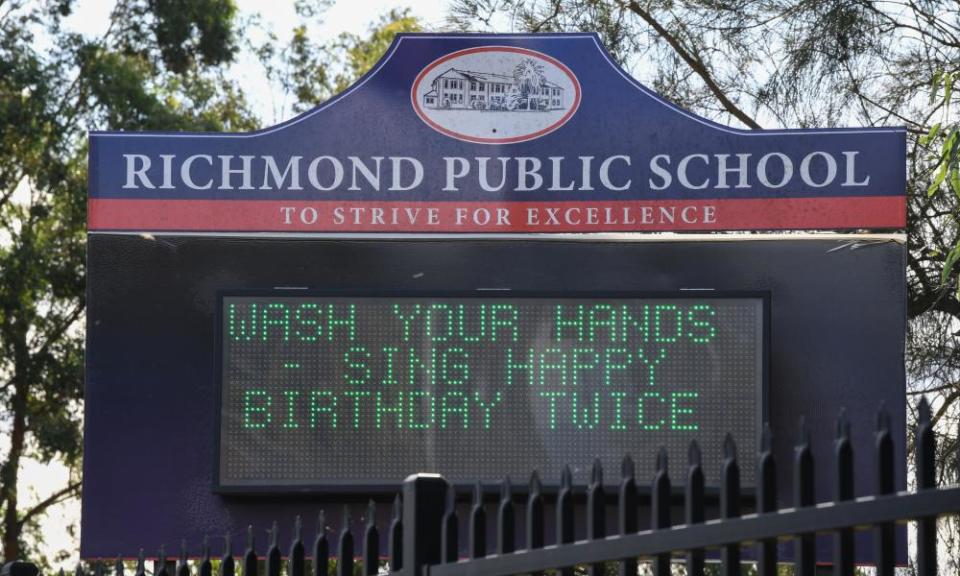

Hand sanitisers on school desks. Schools closed, then opened, and, in some places, closed again. Parents and carers working from home, or not at all. Masked adults at the supermarket. An omnipresent tally of sickness and death in the news and conversations around them. The emotional and physical world of children in 2020 is vastly different to the one they once knew, or that the adults around them expected.

“The ground’s been ripped from under them,” says paediatrician Prof Harriet Hiscock of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

Related: Children's sleep severely affected by impact of coronavirus, say experts

For many children, life will return to normal once the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic and economic crisis lifts. However for many others, particularly those vulnerable due to preexisting mental health conditions or difficult family situations, the disruption, stress and uncertainty of growing up during this crisis threatens to have mental health consequences that will trail them into adulthood, unless they can access mental health support early. That support, Hiscock says, is not yet there.

“I think the system as it is won’t cope with the demand,” she says. “We have to do something about that.”

Coronavirus has hit an Australian mental health care system already under strain. Even before the crisis, many children with mental health problems were not receiving the level of care they needed. Research by Hiscock and others at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute last year found that just one in four children with a mental health condition had accessed professional help.

Chronic uncertainty is much worse for mental health

Now early signs are that demand for mental health support across the board is increasing as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and its fallout. Services such as Kids Helpline have reported a 28% year-on-year increase in calls over the last three months. This week the Australian Psychological Society, as it welcomed the federal government doubling the number of subsidised psychological care sessions that Victorians in need can access, reported that psychologists are experiencing unprecedented levels of demand for their services and that clients were quickly running out of sessions on their mental health plans.

“This [crisis] will see an increase in mental health problems in children and adolescents,” says Hiscock. “If we look at data from previous major events around the world, whether they’re natural disasters or pandemics previously, there are groups of children who go on to have lasting mental health effects into adulthood.”

She says that for children with preexisting mental health issues or for those already struggling with learning or connection with friends, “it’s all got a lot worse for them”. In her Victorian practice, Hiscock says she is seeing children and adolescents who had been “on the edge” begin to retreat from learning and socialising. “Some are just withdrawing to their bedrooms.”

“The mental health challenge is one of the most significant challenges Covid is going to cause,” says Prof Ian Hickie, co-director of the Brain and Mind Institute at Sydney University. “The mental health effects will, at the end of the day, be much bigger than the physical health effects.”

Before Covid-19, anxiety was already the number one mental health issue for children in Australia, says Hickie.

“That depends on the world around them. Do we know where we’re going? Have we got this under control? Is it safe for me to experiment with the world? For everyone’s world at the moment the answer is that, in truth, we don’t know,” he says.

“Chronic stress is much harder to cope with than acute stress. Chronic uncertainty is much worse for mental health. It’s affecting parents and teachers, and it may be transmitting to children. We don’t really know what happens.”

Government needs to take action now ... so that much better services are in place by early 2021

Prof Ian Hickie

The mental health impacts of the crisis will not fall evenly, he says. “It is likely that there will be groups of kids who will be more affected; more anxious kids by temperament, those exposed to more challenging circumstances because of what happens in their families and elsewhere, are likely to have more concerns.”

Economic insecurity alone can lead to negative mental health outcomes in children. A recent Canadian study, co-authored by Dr Nancy Kong, a health economist now at the Queensland University of Technology, tracked children over eight years to determine the impact of family financial instability. They found that in households with economic instability, girls were more likely to develop anxious behaviour while boys more likely to become hyperactive than children in financially stable households.

This impact, Kong says, is likely the result of children mirroring their carers’ worry, or changes in parental behaviour. Parents suffering economic instability were found to be more likely to be inconsistent with parenting, interact less with their children and more likely to use punitive methods of discipline.

Related: What's your emotional style? How your responses can help children navigate this crisis | Lea Waters

Kong says that there is limited research into the effects of economic anxiety on children, but what her study has shown is that intervention needs to be early and specific. Girls and boys may need different interventions, and specific support should be available for single-parent headed households. Without such intervention, the impacts could be long term.

“Imagine a kid is very anxious or hyperactive,” she says. “They’re less likely to sit down in a room and have a productive day of study. So once they develop the bad habits, it’s more likely to carry on and later affects their scores in school, their educational attainment and their labour market outcome.”

‘We don’t want it to be like aged care’

However, the trajectory is not unavoidable. Half of all mental health problems begin before a person is 14, says Professor Hiscock. Three-quarters of adults who suffer poor mental health first experienced problems before they were 25 years old. In Australia, some 14% of children in 2013-14 were reported to have suffered mental ill-health. But early intervention and treatment can prevent problems developing and lingering into later life.

“Mental health problems are preventable and tractable,” says Prof Hickie. “It needs rapid service change.”

The current system, however, say both Hickie and Hiscock, cannot meet the present and coming challenges. A lot needs to change, says Hickie. And quickly. “We don’t want it to be like aged care,” he says, where problems were known but not addressed.

“Government needs to take action now, in the next six months, so that much better services are in place by early 2021 as we see a surge in demand,” Hickie says. Children and young people, he says, have been two groups least well served by the existing mental health system.

A key issue is staffing. There is a known undersupply of child and adolescent psychiatrists in Australia. “We also have a shortage of psychologists who see children under the age of 12 years – even though they say they are child psychologists, they tend to see adolescents,” Hiscock says.

Governments have made a priority of mental health during Covid-19 and the summer’s catastrophic bush fires. Since the pandemic began, money has been allocated to supporting Covid-specific mental health phone lines and funding for psychological care sessions increased. The government has also funded a national pandemic mental health response plan, although Hickie criticises the plan as lacking in practical steps.

Both Hickie and Hiscock say much more needs to be done.

Hiscock says Australia needs to increase its mental health workforce, but also use the existing workforce better. She points to models in the UK and US whereby general practitioners, paediatricians and maternal and child nurses are trained and supported by mental health professionals to address and assess child mental health problems.

A productivity commission report into mental health submitted at the end of June is currently with government. In the commission’s draft report from last October, it warned that children with mental ill health often fall behind in school. It recommended that all schools in the country have a senior teacher dedicated to student mental health and wellbeing and charged with linking in to local mental health support systems. There is not yet a date fixed for the release of the final report.

Hickie advocates for better use of technology in identifying the risks and needs of young people, and signposting appropriate care pathways.

Governments could help reduce anxiety by providing longer term assurances about income support, he says, and parents and teachers could be supported to guide children through these uncharted waters. “A lot of what needs to be done with Covid and mental health is in jobs, education and social cohesion.

“But just like the Covid physical health crisis you need to have a mental health system that works, and it particularly needs to work for children and young people because in a situation of chronic uncertainty and difficulty, they will be two of the groups that will be most affected, and they are where the system itself is often very dysfunctional.

“We’ve been talking about [reform] for 25 years,” says Hickie. “So now’s the test. If you push it down the road, well, you’ve failed the test.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News