The Guardian view on A-levels: ministers, not pupils, have failed

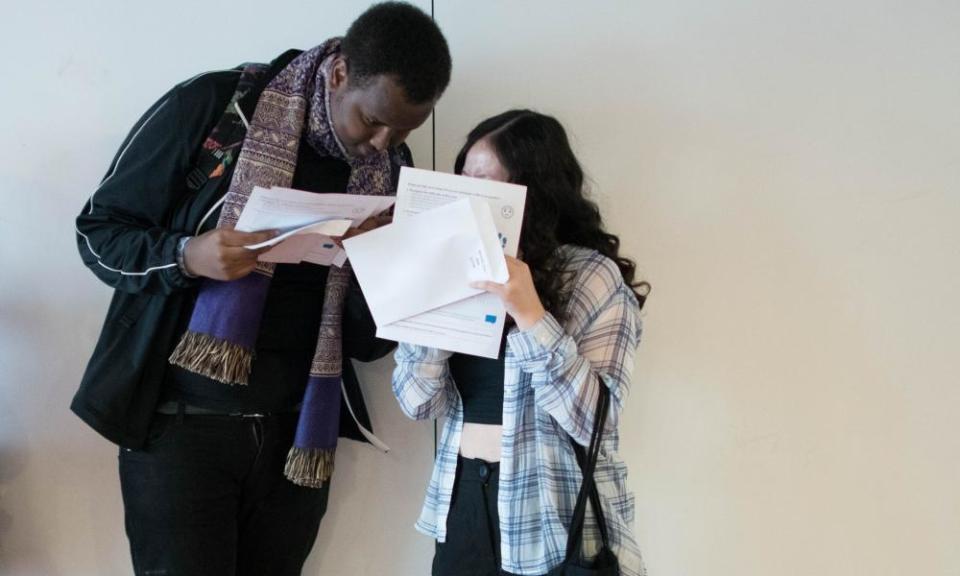

That wealthy pupils and fee-paying schools could tighten their grip on elite universities as a result of the pandemic is not just unfair but grotesque. Yet this is the prospect England faces: a future of entrenched inequality digging in another notch. By using schools’ past performance to determine this year’s A-level grades, ministers chose to favour those with long-established advantages over the up-and-coming. Evidence shows that pupils from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to have had their teachers’ grades overruled, while the gap between pupils on free school meals and others has widened. For a government and, more than that, a country, that is supposed to have rejected the rigid hierarchies of the past in favour of social mobility (at least in principle), results day could hardly have gone more wrong.

The education secretary, Gavin Williamson, has handled the situation poorly. His 11th-hour announcement that the results calculated by Ofqual’s algorithm could in some cases be discarded in favour of mock exam grades revealed weak judgment as well as a lack of planning. When clarity was the minimum that pupils were entitled to, on what is an anxious day even in normal times, the signals have been of panic and muddle. That the situation in England has unfolded in the way that it has, even after a similar row in Scotland, is particularly concerning. Ministers and officials should have seen what was coming.

Students, parents, schools and universities all have reason to be angry. The situation created by the pandemic was difficult – and the Welsh government too is facing criticism. But the five months since schools closed gave ample time for Mr Williamson to seek consensus on a way forward. Pupils, as well as the former chief inspector of schools, Sir Michael Wilshaw, have questioned whether the decision to cancel GCSEs and A-levels and award grades anyway was the right one.

But the blame for this insultingly poor treatment of around 217,000 teenagers does not rest with the Department for Education. Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, apologised for her government’s dreadful handling of Scottish grades. In England it is Boris Johnson who bears ultimate responsibility for the chaos and distress. These extend beyond individual lives – important as they are – to institutions and communities, notably state schools and colleges in poorer areas. With inequalities of all kinds already widening as a result of coronavirus, and poverty expected to go on increasing, any reduction in the educational or job opportunities available to less affluent young people could be even more damaging to society as a whole than in more normal circumstances.

Ministers will not want to recognise it, but the severity of England’s exams crisis, which is likely to worsen when GCSE results come out next week, is the direct result of policies initiated and driven by Michael Gove when he was education secretary from 2010, and Dominic Cummings his adviser. Rigour was their watchword, as they did away with coursework in favour of tests. This week that system has been exposed as brittle. It is one of the ironies of the situation that the less prestigious BTEC qualifications, which are of far less interest to Oxbridge-educated ministers, appear to have passed the pandemic’s stress test much better.

The contrast should give politicians of all parties cause to reflect. But, for ministers, the most urgent step is to explain how they are going to prevent a generation of teenagers from having their life chances limited because of flawed decision-making during the pandemic.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News