Gurus, gas attacks and pubic hair: the strange history of Japan's new religions

This summer, Japan finally executed six long-imprisoned former members of the now-banned radical religious group Aum Shinrikyo. All of them had taken part in the group’s notorious 1995 sarin gas attacks on the Tokyo subway which killed 13 people and injured thousands more. Also executed was the group’s founder, Shoko Asahara.

Founded as a new religion in 1987, Aum Shinrikyo propagated teachings based on Asahara’s interpretation of Buddhism, Hinduism and the practice of esoteric yoga and meditation. At its height, it claimed a membership of 10,000 in and tens of thousands more abroad. But while the sarin attacks were unprecedented and won the group global notoriety, Aum Shinrikyo itself was far from unique.

In the years leading up to the attacks, Japan’s religious landscape produced a wide range of groups pursuing radical social change. Although they presented themselves in very different ways, they all attracted followers seeking a more global awareness, and offered a sense of identity to people feeling disorientated in a rapidly changing society. At the time, I was conducting research and fieldwork in Tokyo, which put me in a position to observe and document not just the gas attacks but the social context in which they occurred.

One group that appeared at around the same time as Aum Shinrikyo was Kofuku-no-Kagaku, which began life as a publishing company that churned out books supposedly penned by its founder, Ryuho Okawa. In 1990, Okawa declared himself first the reincarnation of Buddha, then a supreme divinity by the name of El Cantare. By the mid 1990s, the group was legally a religion in Japan and claimed a membership of 8.25m people,rapidly increasing with overseas proselytisation.

Kofuku-no-Kagaku presented itself as an “innovative” religion, with a fresh and dynamic public image. With a constantly changing cosmology based on social Darwinism and hints of Japanese nationalism, its message and approach matched the ebullient, competitive mood of the bubble economy. Whereas Aum Shinrikyo seemed to appeal to graduates from top universities, Kofuku-no-Kagaku attracted successful writers, journalists, actors, and “professionals” who had returned from overseas and experienced a form of cultural malaise.

It staged media campaigns and spectacular events to attract new members and retain those already “committed” within a tight plausibility structure. In other words, by repeatedly exposing its members to social events, reading materials, meetings and other activities, it constantly reinforced the credibility of its teachings. Fully dedicated members were often rewarded with a job in the corporation’s plush offices in central Tokyo.

Protecting society

Kofuku-no-Kagaku’s moment in the international spotlight came when it block-booked a Ugandan stadium for a religious rally, which meant local athletes had nowhere to practice to qualify for the Olympics. But in Japan itself, its large-scale protests attracted only limited media coverage. That can partly be attributed to its “abrasive attitude” to criticism and its five-year court battle against Kodansha, a major Japanese publishing company that had dared to publish an article in one of its magazines which was seen as insulting to Okawa.

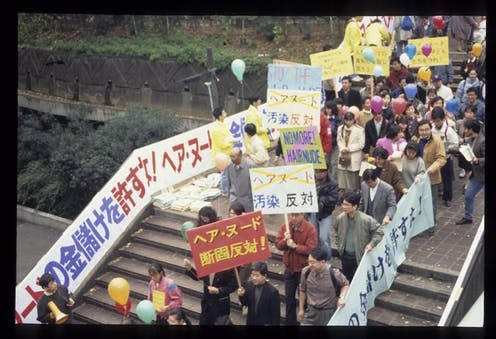

The group’s most eye-catching demonstration at home came in 1994, when a horde of protesters walked from Shibuya to Yoyogi Park in central Tokyo on a November day displaying placards and shouting “stop the hair nudes!”

At the time, pornographic magazines were on sale in many Japanese corner shops, and people would openly read them on crowded trains; some regular newspapers also had a column dedicated to an erotic model or activity. Most of these publications covered up pubic hair with a black square, but more and more magazines were flouting this convention. “Stop the Hair Nudes” was staged to draw the public’s attention to this supposed indecency, and to win Kofuku-no-Kagaku credit for taking a moral stand.

For some protesters, the fact that a number of publishing companies were no longer covering up pubic hair seemed to cause more outrage than the pornography itself. As one protester explained to me: “I wanted to join in the demo to protect Japanese society from being corrupted … as a parent I don’t like society to be corrupted for children.”

Starting in March 1995, Kofuku-no-Kagaku began openly criticising Aum Shinrikyo, stating that as “representatives of religiosity in Japan”, members had a duty to speak out. The group took to the streets of central Tokyo, cruising around in vans with loudspeakers blasting criticism of Aum Shinrikyo and demanding the police investigate its activities. In a lecture I attended in 1994, Okawa himself claimed to know the whereabouts of the Sakamotos, a missing family allegedly abducted by Aum Shinrikyo in 1989.

And just two days before the sarin attack in 1995, I witnessed a demonstration by Kofuku-no-Kagaku members outside Aum Shinrikyo’s Tokyo headquarters. While hardly reported in the press, the protest was seen by some observers as open provocation. An anonymous report in the Japan Times the day after the attack even suggested that the incident may have been orchestrated by one “rival” religious group in an attempt to discredit the other – but with little concrete evidence to support this claim, there was no follow-up.

New life

Times have changed since those strange days. While Aum Shinrikyo disbanded after the sarin attack, many of its members quickly reformed under a new name, Aleph. Even after this summer’s executions, more evidence is emerging of the group’s links to the use of the gas and other suspicious activities.

Meanwhile, Kofuku-no-Kagaku – which now operates under the snappy new English name Happy Science – appears to have assimilated into the mainstream. It now operates “temples”, retreats, overseas branches, and schools. It even boasts a political party, the Happiness Realisation Party, founded in 2009. Its platform promises to “offer concrete and proactive solutions to the current issues such as military threats from North Korea and China, and the long term economic recession”. It has yet to be voted into parliament.

In the aftermath of the events of 1995, the government was forced to reexamine and tighten up existing legislation, which until then meant that virtually any group with a leader, a doctrine and a membership could claim to be a religion. As a result, such groups benefited from tax breaks, and were essentially left to their own devices.

Founding a religion in Japan is far more difficult now than it was before 1995. But as in the case of the Branch Davidian sect led by David Koresh in Waco, Texas, full immersion in a particular vision of society still works. It impels followers to set about making their particular vision a reality – and helps them justify the unjustifiable.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ella Tennant received funding from the University of Hong Kong to conduct the research referred to in this article.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News